Catastrophe (35 page)

Authors: Dick Morris

What do American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Continental Airlines, United Airlines, and US Airways have in common?

All five airlines went to court—through their trade group, the Air Transport Association—to block you, the consumer (and their customer), from having any rights at all when you’re trapped in their planes on airport run-ways for hours and hours at a time.

In December 2007, the Coalition for an Airplane Passengers’ Bill of Rights (http://www.flyersrights.org) persuaded the New York State legislature to pass a law requiring airlines to provide passengers with “food, water, electricity, and waste removal when a flight from a New York airport waits more than three hours to take off.”

508

The law provided for a fine of up to $1,000 per passenger if the airline did not comply.

Food, water, and toilets after three hours. What a radical concept!

Of course, the airlines fought this bill tooth and nail. When the legislature dismissed their objections and passed it, they went to court to block it. After a defeat in the U.S. Federal District Court, they appealed to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, where a conservative panel of judges overruled the law.

Bravo! The airlines shafted their passengers once again!

As air travel increases and airport facilities fail to expand to meet the demand, the problem of lengthy tarmac delays is becoming more and more serious. In the first ten months of 2007, 1,523 flights had to wait on the runway for more than three hours to take off from U.S. airports, nearly a one-third increase over the 1,152 flights kept waiting over the same period during the previous year.

509

And there was a 40 percent increase in lost baggage.

510

The New York State Legislature had to act because Congress has failed to do so. Comprehensive legislation to protect air passengers was passed by the House, but it died in the Senate in 2008 because of Republican opposition.

Canadians are more fortunate. A passengers’ bill of rights, passed by the Canadian Parliament in June 2008, requires airlines to allow passengers to leave the plane after any delay of ninety minutes or more and to reboard the aircraft once it’s ready to take off. The Canadian law obliges airlines to provide stranded travelers with meal and hotel vouchers, except when the delays are caused by bad weather.

The Canadian legislation also provides that:

HOW CANADA PROTECTS FLYERS

Passengers have a right to punctuality.

- If a flight is delayed and the delay…exceeds 4 hours, the airline will provide the passenger with a meal voucher.

- If a flight is delayed by more than 8 hours and…involves an overnight stay, the airline will pay for [the] hotel and airport transfers for passengers…

- If the passenger is already on the aircraft when a delay occurs, the airline will offer drinks and snacks if it is safe, practical and timely to do so. If the delay exceeds 90 minutes and circumstances permit, the airline will offer passengers the option of disembarking from the aircraft until it is time to depart.

511

In the United States, on the other hand, passengers have virtually no protection.

In February 2007, JetBlue Airways became the only airline in the United States to issue, voluntarily, its own Customer Bill of Rights. These self-imposed regulations include:

COMING CLEAN: JETBLUE’S PASSENGER BILL OF RIGHTS

- Guaranteed customer notification of cancellations, delays, and diversions.

- A $1,000 payment for customers who are “involuntarily denied boarding.”

- Free television, food and drink, access to “clean” restrooms, and, medical treatment as needed for customers whose flight is delayed three hours or more after scheduled departure.

- For delays of more than five hours, the airline pledges to “take necessary action so that customers may deplane.”

- A $50 voucher for future JetBlue travel for arrival delays of one to two hours.

- A voucher for future travel—equal in amount to the full round-trip fare the passenger paid—for ground delays that lead to a delay in arrival of two hours or more past the scheduled time.

512

If JetBlue can do it, why can’t American or Delta or United or Continental?

JetBlue was prompted to act, of course, because of its dismal record on Valentine’s Day, February 14, 2007, when more than a thousand passengers were stranded on nine different JetBlue flights at New York’s John F. Kennedy airport due to a snowstorm. As the

New York Times

reported, “the air and toilets on the plane went foul, and the passengers, who well understood the impact of snow, were given little or no information about why they

couldn’t just be set free in the terminal. Roll a stairway over? Bring a bus? Allow them to walk? No? Why not?”

513

As JetBlue’s CEO, David Neeleman, said, despite the weather conditions, there was “no excuse” for the company’s performance that day.

JetBlue’s Bill of Rights must have heartened its frequent flyers, but things didn’t necessarily improve on the other big airlines. Kate Hanni, a passenger who was stranded for eight hours on the runway on an American Airlines flight on December 29, 2007, was so outraged at the “indifference” that she said the airline showed to her that she founded the Coalition for an Airline Passengers’ Bill of Rights.

The

Wall Street Journal

described the scene:

After hours of sitting on the runway, the toilets on the American Airlines jet were overflowing. There was no water to be found and no food except for a box of pretzel bags. A pregnant woman sat crying; an unaccompanied teen sobbed. The captain walked up and down the aisle of the MD-80, trying to calm angry passengers. At one point, families with children lined up to be bused to the terminal, but a bus never came.

514

Eventually, Hanni’s flight—scheduled to run from San Francisco to Dallas—was diverted to Austin, Texas, because of thunderstorms. Finally, as the

Journal

reported, “after eight hours on the runway and twelve hours, total, on the plane, the captain told passengers he was going to an empty gate, even though he didn’t have permission.”

515

And why didn’t he have access to the empty gate? It appears that, with thunderstorms in the region, “according to airline officials, Austin managers decided to focus on handling regular flights to other cities such as Chicago and St. Louis, hoping they could stay on schedule.”

516

This “pivotal decision” meant that Hanni’s flight had to sit and sit and sit on the runway.

517

American Airlines was not totally insensitive as its plane sat on the runway. Like a hostage taker who lets women and children go, the airline “allowed about 20 local Austin and San Antonio passengers to get off rather than wait to fly to Dallas only to hop back on a connection back to Austin.”

518

Their luggage, not so fortunate, had to remain on board.

As the

Journal

reported, “conditions in the…cabin quickly dete

riorated—toilets overflowed, families ran out of baby diapers. American did not act to empty the toilet tanks until the plane had been stuck on the ground for more than five hours.”

519

Meanwhile, American was cheerfully using its four operating gates for regularly scheduled flights and the captain was telling his captives he couldn’t find a gate.

Of course, American was only acting in its own self-interest. Airplane delays are cataloged by the federal government, and taking unusual measures to accommodate the stranded flight and letting the passengers off could have triggered a domino effect and caused dozens of delays, which would have looked bad for American’s on-time record. But without any passenger bill of rights, the airline incurred no penalty for keeping the passengers locked for hours in a stale and sweltering airplane with no food.

While JetBlue responded to its abysmal performance by embracing a passenger bill of rights, American—and other airlines—continue to battle against any such regulation in Congress, the state legislatures, and the courts.

Of course, punishing airlines for delays and requiring that they permit passengers to deplane, get food, or use the bathroom, would worsen their on-time record. Returning to the gate could cause planes to lose their place in line for takeoff and might even run afoul of federal limits on crew work-days.

Currently, the FAA’s “8/16” rule limits a pilot’s total work day to sixteen hours, including a maximum of eight at the airplane’s controls. The rule, of course, is designed to stop tired pilots from flying. A pilot cannot start a new flight that would push him over the eight-hour limit, but he can continue a delayed flight for up to sixteen hours. So if the plane returns to the gate and the delay would push the pilot’s workday over eight hours, he may not fly the plane. If he sits on the runway, on the other hand, he can take off.

Requiring compensation for customers who are delayed for many hours; banning long tarmac delays; and obliging airlines to offer food, water, and clean restrooms to delayed passengers: such regulations would trigger a shocking entire new priority for airlines—the passenger would have to come first. Airlines might have to maintain standby crews waiting to fly if delays force a crew to go beyond their allotted work time. Air traffic control

systems might have to give airplanes credit for time spent returning to the gate and keep them from losing their place in line for takeoff.

The FAA will have to adjust its rules to protect passengers.

It’s about time it did!

The closest we’ve come to an airline passenger’s bill of rights was the bill that was sponsored by Congressman James Oberstar (D-MN) and passed by the House before it was killed in the Senate. The chairman of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, Oberstar ingeniously inserted the provision into legislation extending the life of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), which also gave airlines $500 million in taxpayer-funded “war insurance” protecting them against disruptions in service.

520

The U.S. Department of Transportation tried to address the issue of tarmac delays by appointing a task force to recommend improvements in how passengers are treated during such delays. While the task force urged airlines to provide for “better communication and improved preparedness to provide stranded passengers with food and water,” the nonbinding “model contingency plan” did not suggest set time limits for forcing a return to the gate, nor did it call for mandatory steps to improve service to passengers who were stranded.

521

In short, it did next to nothing. Its mealy-mouthed provisions were adopted by a vote of 34–1, the lone opponent being Kate Hanni, the head of the passenger advocacy group, who had been appointed to the commission as a sop to the public.

But Hanni was not entirely shut out. The one proconsumer recommendation the task force made was to allow airlines to be sued in state court. The doctrine of federal preemption bars state courts from hearing any cases that relate to “routes, rates, or services” provided by airlines.

522

But the DOT task force recommended that airlines be required to specify what they would do for passengers who are stuck on the tarmac in their contract of carriage with the passenger (the microprint on the back of your paper ticket). If they did so, passengers could sue for violation of contract—an action that could well be heard in state court.

In light of the possible results, the airlines have declined to endorse the task force’s recommendations out of fear of what might happen if state courts should get jurisdiction.

The reason Congress won’t act to protect air passengers, of course, is that its members are beholden to the airlines for campaign donations and all sorts of other favors. The airlines have ratcheted up their donations to members of Congress from $2.7 million in 2004 to $3.5 million in 2008.

523

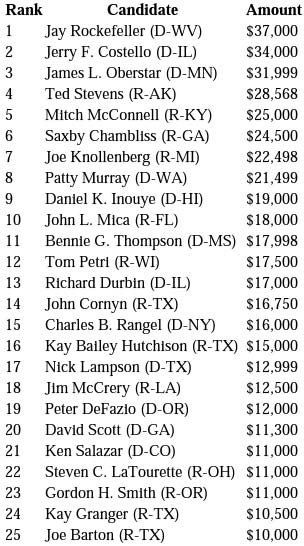

Here is the list of the members of Congress who have gotten the most in campaign contributions from the airlines and their PACs. Notice the first name on the list: Senator Jay Rockefeller from West Virginia. Guess what? He’s the chairman of the Senate Transportation Committee!

AIRLINES: TOP PAC RECIPIENTS, 2008

Source:

“Airlines Top PAC Recipients,” Center for Responsive Politics, www.opensecrets.org/industries/pacrecips.php?ind=T1100&cycle=2008.

But sometimes the airlines don’t stop at campaign contributions; sometimes they grant special favors. For example, in the fall of 2008, right after the House and Senate voted on the TARP bailout for the nation’s major financial institutions, a number of them got together to send New York Democratic congressman Charles Rangel, the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, and five other congressmen on a junket to the Caribbean.

524

American Airlines provided free tickets for the members—even though its gift violated House ethics rules.

ACTION AGENDA

You don’t have to let the lobbyists and the airlines have the last word. You can act to force adoption of an airline passengers’ bill of rights.