Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War (46 page)

Read Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War Online

Authors: Max Hastings

Tags: #Ebook Club, #Chart, #Special

Soldiers began to laugh, then to cheer. Bridges harangued them, shouting that he would take them back to their regiments. One by one they roused themselves and fell in. Darkness had fallen. Bridges and his trumpeter, reinforced by a brace of mouth organs, led his motley column out of Saint-Quentin. Some of them indeed rejoined II Corps’ line of march, but four days later 291 men of the Warwicks were still missing, listed as ‘stragglers’. Both defaulting colonels, John Elkington of the Warwicks and Arthur Mainwaring of the Dublin Fusiliers, were cashiered for their attempted surrender: on 14 September, Army Orders recorded their convictions for ‘behaving in a scandalous manner unbecoming to the character of an officer and a gentleman’. Elkington, though forty-nine years old, responded in a manner worthy of fiction by joining the French Foreign Legion, with which he lost a leg and was awarded the Legion of Honour. King George V later reinstated him in the British Army and gave him a DSO, but the colonel spent the rest of his life as a recluse, declining ever to wear his medals. One of the Warwicks’ young officers was Bernard Montgomery, who in his later memoirs made it plain that he did not think much of Elkington, and recognised a shambles when he saw one, at Le Cateau.

Another battalion’s CO, by contrast, spoke of the aftermath of the battle with partisan regimental pride: ‘I ran into what appeared to be a disorganised mass of soldiers of all sorts of units, mixed up together. They were leisurely retiring, but in no sort of formation. There was no panic, only disorganisation. [Then] I sighted the Wiltshires, marching along the road all in good order, ready for action wherever required.’ They reached Saint-Quentin, twenty miles south-east of their battlefield, early on the 27th. By dawn the following day, II Corps was at the Somme, thirty-five miles from Le Cateau, having shown that most of its men could march as hard as they could fight.

If Sir John French’s contribution to the conduct of the British campaign since Mons had been erratic and inglorious, it was his good fortune that the enemy did worse. Kluck, commanding far larger forces, manoeuvred them ineptly, missing repeated opportunities to trap the vulnerable British. On the 27th the German general compounded earlier mistakes by maintaining his army’s southerly line of march, while the British veered south-eastwards on a line towards Paris, untroubled by the enemy. That day, the French divisions on their left received most of Kluck’s attentions.

One consequence of the C-in-C’s moral collapse – for it is hard to define his conduct as anything less – is that it caused his liaison officer with GQG, Col. Charles Huguet, to report to Joffre in the most despondent and defeatist terms. The Frenchman declared on the 26th: ‘battle lost by the British Army, which seems to have lost all cohesion’. In the days that followed, gloom took hold in the rear areas of the BEF. Huguet sent a further message on the 27th in which he asserted: ‘conditions are such that for the moment the British Army no longer exists. It will not be in a condition to take the field again until it has been thoroughly rested and reconstituted.’ The colonel is often castigated by British writers for his pessimism, but this is unjust. What Huguet said merely reflected the hysterical view prevailing at GHQ in general, and in the mind of its commander-in-chief in particular.

The muddle of stragglers, and the conspicuous distress of some senior officers, bred a virus of panic which eventually spread to London. Huguet suggested that Sir John French might insist upon withdrawing the BEF to Le Havre. The C-in-C was indeed attracted to a fantastic notion that his army might retire from the campaign for a few weeks, to reorganise and refit, while his senior staff officers did nothing to restore confidence. Henry Wilson sent a message to 4th Division’s commander: ‘Throw overboard all ammunition and impediments not absolutely required, and load

up your lame ducks on all transport, horse and mechanical, and hustle along.’ The same order was given to II Corps. Smith-Dorrien immediately countermanded it, only to be rebuked by Sir John French for having done so.

The despondency at the top was almost entirely unjustified. Haig’s I Corps had scarcely been engaged. Most of II Corps’ units were suffering from nothing worse than exhaustion; their fighting spirit was unimpaired. Men were bewildered that they continued to flee before the enemy. Since they could not see the great grey masses of Kluck’s and Bülow’s armies, they were cockily confident that, on the Germans’ showing thus far, they could lick them. Their commander-in-chief, however, saw only one choice: opposed by overwhelmingly superior numbers, and alongside allies in whom he had lost all confidence, the BEF must continue its flight, if possible as far as the sea. Only the robust good sense of quartermaster-general Sir William Robertson, who organised dumps of ammunition and rations along the army’s line of retreat, enabled the troops to remain fed and capable of fighting.

The BEF marched two hundred miles between Mons and the Marne, averaging four hours’ sleep a night. Three exhausted Irish Guardsmen, literally sleepwalking, shuffled southwards clinging to the belt of their adjutant, Lord Desmond Fitzgerald. On 28 August Guy Harcourt-Vernon wrote: ‘Marches are much slower now, but we cover the ground somehow.’ At halts, they cut wire from farm fences to make defensive entanglements, and dug potatoes from the fields with a sense of guilty delight at being licensed to steal. Bizarrely, on 29 August the Grenadiers spent two hours holding a routine pay parade.

And spasmodically they scuffled with Germans. The Connaught Rangers had made a notable contribution to the culture of the war by singing ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ as they first disembarked in France. George Curnock,

Daily Mail

star reporter, heard the song and mentioned it in a dispatch. The paper’s news editor wrote in his diary: ‘The chief [Lord Northcliffe] has given us orders to boom it, to print the music so that everybody shall know it. He says, thanks to Curnock’s genius, we shall soon have everybody singing it.’ And so they did. But on 26 August the Connaught Rangers had a much less happy experience. They were acting as rearguard when they failed to receive an order to retire; six officers and 280 men were lost, including their colonel, almost all taken prisoner.

On 27 August, 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers suffered even more severely. The unit was commanded by an officer of French descent named Paul

Charrier, who three weeks earlier had enthused about the prospect of fighting the Germans, his people’s hereditary foes. North of Etreux, the Munsters fell victim to yet another of the campaign’s communications breakdowns: missing an order to pull back, they were cut off. The Irish soldiers attempted to escape down roadside ditches while a Maxim gun kept the enemy at bay. They were finally cornered in an orchard, where they fought until evening, when the Germans used a herd of cattle to mask their final assault. Four wounded Munsters officers and 240 men were taken prisoner, while ten officers and 118 other ranks were killed – including Charrier, a figure of notable eccentricity who fought wearing a sola topee; he was twice wounded leading counter-attacks before succumbing. Another of the dead was a certain Lt. Awdry, said to have fallen with his sword in his hand, whose brother later achieved an incongruous celebrity as author of the children’s tales of

Thomas the Tank Engine

.

Elsewhere, driver Horace Goatham’s best mate in his 18-pounder battery put a hand over his horse’s back to mount, and promptly received a bullet through it. Goatham somehow pushed the man onto another horse and whipped up the gun team. After a time, however, his mate slumped in the saddle from loss of blood, then slid to the ground. The gunners were fortunate enough to meet a field ambulance wagon which picked up the wounded man, who reached safety, as others did not. Goatham’s worst subsequent experience came when his battery reached a river where the bridge had been blown. Only a precarious Royal Engineers’ pontoon offered a route southwards, with German shrapnel bursting around it. ‘We had to wait till the shells burst, then gallop like hell over, one gun at a time. We lost one team, blown all over the shop. My off horse got hit, but we got clear. If ever men deserved to be decorated, every manjack of those REs did, for as fast as one got bowled over and fell in the water another would run along the bridge and jump in the [pontoon] boat to replace him.’

A sergeant of the Oxf & Bucks shouted repeatedly during those days, ‘Stick it lads! We are making history!’ If such histrionics read well to posterity, however, they merely exasperated the weary men whom he addressed. Cpl. Bernard Denore of the Berkshires was better pleased when his pal Ginger Gilmore found a mouth organ and staggered along at the head of the company playing tunes ‘despite the fact that his feet were bound in blood-soaked rags … Mostly he played “The Irish Emigrant”. Which is a good marching tune … An officer asked me if I wanted a turn on his horse, but I looked at the fellow on it and said, “No thanks.”’ Others were less unselfish. When the medical officer of the Royal Welch dismounted to attend a wounded man, he asked a passing Cameronian to hold his reins. The man promptly scrambled into the saddle and cantered away, leaving the hapless doctor to continue his own progress on foot.

Horses soon began to go lame in large numbers, many because they needed shoeing, and there were no smithies at hand. Limping and dead animals littered the line of march, along with discarded carts and equipment. Driver Charles Harrison and his mates subsisted chiefly on raw vegetables picked from roadside fields. Several later found themselves in trouble for losing their caps, which slipped off as their heads slumped in sleep, even as they rode. And all the while the retreating army competed for road space with dense columns of refugees, incongruously clad in their Sunday best, because that was what they always wore for leaving their own villages – as some now did at the commencement of a four-year exile.

The manner in which the campaign flooded across France, swamping a large tract of a great country not yet adjusted to war, produced some bizarre encounters. When the Royal Flying Corps headquarters staff found themselves in need of automobile tyres and headlights, on 29 August an officer simply drove to the Daimler showroom in Paris and purchased as many as his vehicle could carry, paying in gold sovereigns from a bulging portmanteau entrusted to him for such purposes. ‘

Les anglais sont épatants

,’ marvelled the French salesman, shaking his head in admiration for these ‘wonderful’ people. The jumble of ancient and modern was illustrated by the experience of exhausted RFC pilots, who one night during the retreat slept fully dressed on a straw stack in a barn, while their machines in a neighbouring field were guarded by a squadron of the Northern Irish Horse.

A staff officer dispatched on a liaison mission from I Corps met Smith-Dorrien and his staff on the 29th, and recorded in his diary that he found the mood at II Corps utterly different from that of GHQ, and anything but cast down: ‘quite calm, approachable and pleasant; not too busy to say a cheery word or two, and quite unfluttered’. But some officers felt that the morale of the entire BEF was sagging. Col. George Morris of the Irish Guards – who would be killed two days later – was ‘very gloomy’, telling a fellow officer ‘it was the old story of allies failing to get on together and that everything was going wrong … we should be re-embarking for England in a fortnight’. Guy Harcourt-Vernon wrote home on 29 August: ‘the marches have been awful & unless we get a day of rest soon we shan’t

have a man in the ranks’. But then he added, after a few hours’ priceless repose: ‘We shall be able to carry on for a long time yet. It is wonderful what a different view of life you take after a sleep & meal.’ Yet still they continued to retreat southwards day after day, as did the French armies on their right.

On 25 August Lt. Col. Gerhard Tappen, Chief of the

Operationsabteilung

of the General Staff, declared with satisfaction: ‘In six weeks we shall have the whole job done.’ Whatever the significance of Mons, Le Cateau and comparable French actions in allied minds, the only reality that seemed to matter to most Germans was that they continued to advance, and to repulse every French counter-attack. By the 27th the high command had tacitly, if not explicitly, abandoned its plan to encircle Paris from the west, deciding that it was now necessary only to hound the beaten foe to destruction. The German army’s successes spawned a huge misjudgement. After inflicting vast casualties on the French, Moltke and his subordinates failed to recognise that, in history’s greatest clash of arms, even such carnage did not suffice to destroy an enemy’s powers of resistance. A fatal complacency overtook the Kaiser’s commanders in the last days of August and the first of September: they persuaded themselves that a coherent strategy was no longer necessary to complete their triumph.

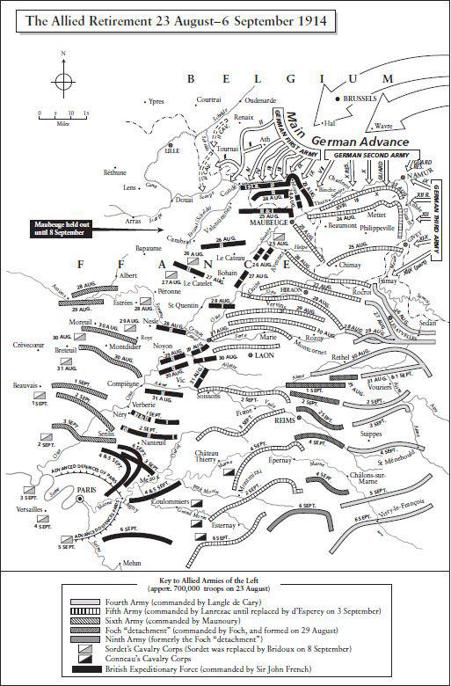

Yet in some places, notably the Lorraine front, the advancing Germans were now suffering almost as severely as the retreating French. On 25 August Joffre’s forces launched a counter-attack in the Trouée des Charmes between Tour and Epinal, a difficult country of steep hills and rivers. In what became known as the Battle of the Mortagne, some 225,000 French soldiers clashed with 300,000 of Prince Rupprecht’s men. Fighting petered out in a draw on 28 August, but the Bavarians had bled freely for small advantage – one historian estimates that they suffered 66,000 casualties in Alsace-Lorraine. The Germans’ advance slowed, especially that of Hausen’s Third Army: at least until early September, Moltke’s commanders acknowledged a need to keep step with neighbours, which sometimes required holding back their own men. On the evening of the 29th came a decisive moment: Bülow invited Kluck, his subordinate, to change his axis of advance, to wheel inward – further east – to strike a killing blow at Lanrezac’s Fifth Army. This initiative was duly adopted without authorisation from the chief of staff, yet it represented a critical departure from even OHL’s modified version of the Schlieffen concept. Next day Moltke acquiesced. He too seemed to suppose that it was now merely necessarily

to herd the shattered French armies south-eastwards, towards the Swiss frontier.