Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War (55 page)

Read Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War Online

Authors: Max Hastings

Tags: #Ebook Club, #Chart, #Special

The Times

editorialised flatulently: ‘The British Army has surpassed all the glories of its long history, and has won fresh and imperishable renown … Though forced to retire by the overwhelming strength and persistence of the foe, it preserves an unbroken if battered line.’ It is hard to exaggerate the impact of the paper’s report on public opinion. Its publication enraged the rest of the British press, which had obeyed government injunctions to sustain morale with a diet of platitudes. Asquith denounced the story, and dismissed Moore’s conclusion that the army was broken. But the storm about the

Times

dispatch was still raging when the commander-in-chief’s secret telegram arrived, offering much the same view of the BEF’s condition as that of the ‘sensationalist’ press correspondent. Both were wrong, and exaggerated grossly. But French’s defeatism threatened dire consequences: he informed the prime minister that he proposed to retire beyond the Seine and establish a new logistical base at the port of La Rochelle. The C-in-C no doubt thought of himself as Sir John Moore in Spain a century earlier, saving his gallant little force by retreat to Corunna.

The wildest rumours were circulating in London, reflecting cruelly and unjustly upon the French army. Norman Macleod recorded in his diary reports of a wholesale collapse; of the British C-in-C supposedly threatening to withdraw the BEF to England; of a French cavalry division allegedly refusing to support hard-pressed British troops, ‘saying they were tired’; of the BEF fighting continuously for eleven days until ‘flesh and blood could stand no more’. The Fourth Sea Lord told Macleod wearily that it looked as if Britain would once more have to save the French in spite of themselves, as Wellington had once saved the Spanish. Next day, this dignitary confided: ‘the French have been told that they must fight or go to the devil’.

Such, then, was the fevered climate at Westminster and in Whitehall amidst which the cabinet received Sir John French’s telegram. It was an incomparably grave matter, that the C-in-C of Britain’s army in the field should advise washing his hands of the campaign, which was what his proposal amounted to. The notion of the BEF unilaterally disowning France’s army threatened devastating consequences for the allied cause. The cabinet made a critical and by no means inevitable decision: Anglo-French solidarity must transcend all other considerations. The field marshal must be overruled. He would be given a direct order to keep the BEF alongside the armies of Joffre in the line. The secretary for war, K of K, was dispatched forthwith to Paris to ensure that Sir John did as he was told. The C-in-C must abandon his shamelessly base attempt to desert France.

On 1 September in the French capital, even as L Battery and the Guards brigade were fighting their little battles at Néry and Villers-Cotteret, a momentous meeting took place at the British embassy, Pauline Borghese’s former palace in the Rue Saint-Honoré. Kitchener, hotfoot from London, chose this rendezvous with Sir John French, summoned from Compiègne. The C-in-C later professed disgust, first at having to leave his headquarters to meet Kitchener at all, and second that his fellow field marshal, now a mere civilian war minister, attended in uniform. French denounced the visit as an unwonted political interference with his own ‘executive command and authority’, and summarily rejected Kitchener’s proposal to see for himself the BEF in the field. In truth, the C-in-C must have felt sorely inadequate in the company of a much cleverer soldier than himself, who wore the French commemorative medal for the campaign of 1870–71, belatedly presented to Kitchener the previous year. Following a tense and indeed acrimonious meeting, an uneasy compromise about operational plans was agreed: Sir John should continue the BEF’s withdrawal, but was ordered to act in close conformity with Joffre’s plans, while taking care to secure his flanks.

In the four days that followed, French’s determination to exploit to the limit the escape clause about flanks drove Joffre and his comrades towards despair. The British C-in-C interpreted these orders as empowering him to reject repeated pleas to participate in an allied counter-offensive. French’s overriding purpose was to keep his men marching until the Seine was interposed between them and the Germans. John Terraine has written: ‘Uncertainty about British intentions, their apparent determination to do nothing but retreat while the Germans over-ran the greater part of northern France, added enormously to Joffre’s difficulties.’ These were very great. Gallieni later described the condition of the nation’s armies – admittedly with a strong partisan interest in promoting a vision of chaos until he himself took a grip – in a fashion that nonetheless carries conviction. He wrote of meeting generals behind the front who had lost their troops; troops who had lost their officers; commanders who had no idea where they were, or where they were supposed to be going. On 2 September, Paris’s governor spoke by telephone to Joffre, who expressed his fears for the left wing of Fifth Army ‘because of the inertia of the British who don’t want to march’.

The British Army has been accustomed in almost all its wars – including that of 1939–45 – to enjoy the luxury of months, or even years, of preparation before being obliged to fight in earnest. Such a delay was anyway usually inevitable when the nation had to muster expeditionary forces then transport them overseas, sometimes across vast distances. By contrast, the events of 1914 imposed a uniquely abrupt trauma: within three weeks of being plunged into a wholly unexpected European conflict, soldiers were translated from parade grounds, pubs, officers’ messes and polo pitches to the carnage of a battlefield. For some – commanders amongst them – the change proved too drastic to be borne. They showed themselves unable to make the necessary psychological leap to rise to their roles in a drama on which the fate of Europe hinged. On the night of 31 August, Spears heard Lanrezac murmuring to himself with an unaccustomed softness and wistfulness of tone. The general was paraphrasing Horace: ‘Oh how happy is he who remains at home, caressing the breast of his mistress, instead of waging war!’ Such capitulations to sentiment by officers who failed their countries in August 1914 merit pity, but not sympathy. No man should accept high responsibility unless he is willing to bear its burdens.

For those on urgent business in those days, movement around Paris was rendered maddeningly slow by throngs of troops, vehicles and refugees clogging every byway behind the front. A British officer found himself forced to abandon his car and walk one night, along a road blocked by a motionless regiment of cavalry: ‘The great towering cuirassiers, clumsy and massive in helmets and breastplates, sat impassive on their horses. Not a man dismounted. In the still evening air the booming of the guns seemed

very near. A gust of wind animated the horsetail plumes that hung down each man’s back, then the long steel-clad column was still again.’ An officer of Fifth Army’s staff, Commandant Lamotte, was obliged to drive repeatedly into Paris to urge the military-map printers to greater exertions. They were confronted by an insatiable demand for sheets covering France, while tens of thousands of paper representations of western Germany, carefully stockpiled in expectation of Joffre’s grand advance, mouldered in a vault through the balance of the conflict.

The last days of August and the first of September witnessed some allied heroism, but also scenes reflecting ignobility and squalor. Disgust was often expressed about German pillage in France, which was real enough; less was said about the excesses of retreating French and British soldiers, some of whom looted ruthlessly – especially alcohol. Edouard Cœurdevey recoiled from the spectacle of destruction created in Le Mesnil-Amelot in the Oise not by the enemy, but by French colonial troops: ‘The owners of the big farms live in unimaginably luxurious houses: crystal vases, pianos, billiard tables, sumptuous beds, all of which have been overrun by a savage soldiery. They have ripped open everything closed, thrown the contents onto the floor, pillaged what they pleased, dirtied everything that was no use to them, broken family portraits, thrown linen and women’s underwear on the floor, scattered provisions everywhere on beds, billiard tables and pianos. China lies smashed on the ground; some [soldiers] have [defecated] on the beds. The Germans wouldn’t have done worse.’

The armies’ medical facilities were overwhelmed by the scale of casualties. Around a third of British wounded who reached dressing stations subsequently died of gangrene. In the French army, medical aide Lucien Laby recorded that his own ambulance alone collected 406 casualties in the first month of the war, 650 in the second. Often, it was impossible to evacuate them during daylight, and by night they were hard to locate even with the aid of some of the French army’s ‘

chiens sanitaires

’ – 150 dogs specially trained for the role. Laby became accustomed to making summary and ruthless judgements: he abandoned those with no prospect of survival, and in some cases claims to have ended their sufferings with his pistol. His only equipment was a supply of dressings; he staunched one man’s haemorrhage by placing two hardtack biscuits on the wounds and applying a bandage as tightly as possible.

Inside dressing stations there were no lights, and often deep mud. Laby wrote: ‘What horrors! How many wounded men! All of them beg us to

look after them and to take them first. A cellar is full of them as well as the whole house – in every room and on all the beds.’ Even evacuees fortunate enough to find space on overcrowded trains could expect little relief in the rear. Many received their first hospital treatment only after a lapse of four or five days. Tetanus was a massive killer. A chaplain at the American hospital in Neuilly described how he and colleagues asked each man where he was hit. ‘Several silently point to their throat, their head, their side. Some lift their covers to show great black patches surrounded by splashes of red. There is a sickly odour … This morning I gave absolution to a Lyonnais: his brain laid open, half his body paralysed but still quite conscious and sensible and able to answer yes or no to questions asked him.’

More than a few able-bodied soldiers exploited the chaos of the retreat to slip away from their units, some to rejoin later, professing to have become lost, others content to lag behind and become prisoners. Sir John French and his staff were not the only senior officers to succumb to defeatism: Gen. Joseph de Maistre, chief of staff of First Army, later told Spears that during the August disasters he seriously contemplated shooting himself. The British officer described a scene on 1 September, as men of Fifth Army continued to fall back north-east of Paris: ‘They looked like ghosts in Hades expiating by their fearful endless march the sins of the world. Heads down, red trousers and blue coats indistinguishable for dust, bumping into transport, into abandoned carts, into each other, they shuffled down the endless roads, their eyes filled with dust that dimmed the scalding landscape, so that they saw clearly only the foreground of discarded packs, prostrate men, and an occasional abandoned gun.’

Civilians struggled to avert the consequences of the tidal wave sweeping over their communities, some great and some small. The mayor of a hamlet named Défricheur interrupted a party of soldiers sweating as they dug a grave for a horse, to complain bitterly that it was too close to people’s houses. Grumbling, the soldiers moved away to begin their labours anew in a field. Few units on either side found time to bury dead men, never mind dead animals. ‘It is extraordinary how one gets used to this nomadic life,’ wrote Edouard Cœurdevey, ‘sleeping and eating here and there and not thinking of anything important because we know nothing. We see neither letters nor newspapers and cannot share in the drama which is unfolding … We march, stupid and mute – slaves of the god of war.’

Only a handful of the uniformed millions engaged on both sides of this movement of humanity, resembling a terrible animal migration, had any

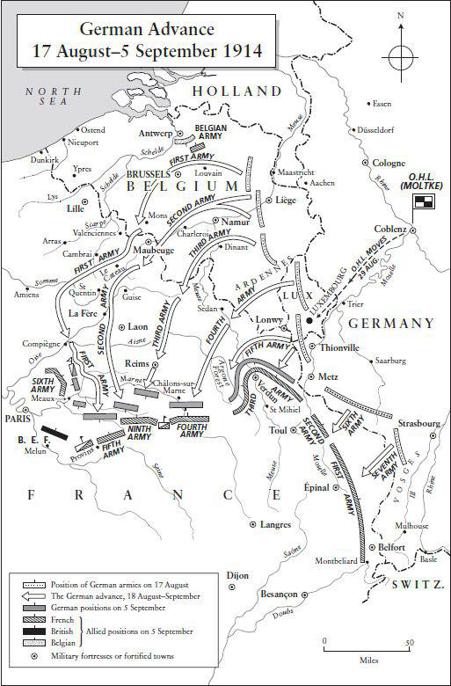

hint of the change of fortunes that was stirring. Joffre could boast some strategic gains from the events of August. Albeit at dreadful cost, the French onslaughts in Alsace-Lorraine had made it impossible for the Germans to shift troops to reinforce their right flank in Belgium. The Entente armies were growing stronger, as troops arrived from overseas colonies; Italy’s declaration of neutrality allowed France to remove the defenders of its southern border to reinforce the Western Front. Thanks to Fifth Army, d’Amade’s Territorials and the BEF, the Germans had lost the race to achieve decisive success in the north before Joffre redeployed to present first a shield and then a sword against their advance.

Throughout late August and early September, trains from the south crammed with men, vehicles, guns, horses were offloading north of Paris, joining the new Sixth Army of Gen. Joseph Manoury. German Alois Löwenstein, a mere lieutenant, wrote home that the French fought hard, and were well-led. ‘Above all,’ he said, ‘they have the capacity to move huge masses of troops quickly & thus to attack our weakest points with superior numbers.’ This remark reflected a sharper awareness than was displayed by Löwenstein’s immeasurable superiors of the General Staff about the capabilities of the French railway system, now being exploited to critical effect.