Catastrophe: An Investigation Into the Origins of the Modern World (17 page)

Read Catastrophe: An Investigation Into the Origins of the Modern World Online

Authors: David Keys

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #Geology, #Geopolitics, #European History, #Science, #World History, #Retail, #Amazon.com, #History

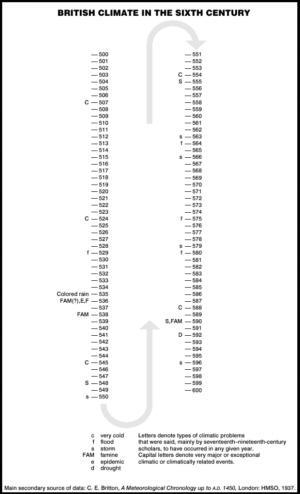

The significance of this information lies not in each individual entry but in the statistical concentration of them in the years 535–555, compared with the rest of the period. Yet despite the apparent severity of the climatic conditions and despite the famine (538 or possibly 536 in Ireland and almost certainly also in mainland Britain) associated with their onset, these events probably did not have any lasting impact, at least not directly. Interestingly, however, the period of the famine was much later (possibly as late as the mid–tenth century) reported—or more probably “selected”—as the death-date of King Arthur,

A

.

D

. 537. It was instead an indirect effect of the 530s climatic chaos which was to wreak major and permanent change on Britain.

In c. 549 the bubonic plague, having swept up from East Africa and across the Middle East and Europe, finally reached the shores of the British Isles. In Ireland, the

Annals of Ulster

record that “a great epidemic” (a

“mortalitas magna”

) broke out. Of the aristocracy, at least six important figures—Finnia, Moccu, Telduib, Colam, Mac Tail, Sinchell, and Colum of Inis Celtra—are said to have perished. In Wales, the

Welsh

Annals

also reveal that in 547 (corrected to 549 by some modern historians) the king of Gwynedd, a powerful monarch called Maelgwn, died of plague.³

The plague (which, as already described, had started in East Africa a decade earlier) almost certainly entered Britain on board ships that had come from either southwest France or, more likely, from the Mediterranean itself. As elsewhere, the carriers of the dread disease were stowaway black rats. There would have been plenty of opportunity for the epidemic to enter Britain because trade between the Mediterranean and the western part of the British Isles flourished in the first half of the sixth century, right up to the time of the plague.

Two key locations stand out as the most likely initial points of entry for the disease: Tintagel, on the north Cornish coast, and Cadbury Congresbury, on the river Yeo, two miles from the Bristol Channel. Both places were likely to have had direct contact with ships originating in the Mediterranean.

Tintagel—the mythical place of King Arthur’s conception—appears to have been a royal citadel in the fifth century and the first half of the sixth. A substantial number of stone buildings from the period have been discovered on the site, as have considerable quantities of imported Mediterranean pottery. Excavations so far—in a relatively small percentage of the site—have unearthed three thousand fragments, and it is likely that tens of thousands more shards still remain to be discovered. An analysis of this unearthed material reveals that the royal elite at Tintagel were importing fine tableware from Phocaea in what is now western Turkey, other tableware items from the Carthage area (now Tunisia), jars from Sardis in western Turkey, and olive oil or wine amphoras from both Cilicia (southern Turkey) and the Peloponnese in southern Greece.

The Mediterranean influence at Tintagel may have gone even deeper than merely satisfying exotic tastes for fancy tableware and wines. Traders or even diplomats from the Roman world may well have lived at the royal court there. Excavations at a churchyard near Tintagel have unearthed two indications of a more pervasive Mediterranean influence—slate tablets bearing stylized crosses of a type more usually found in the Mediterranean region, and remarkable evidence of graveside funerary feasts—again, things more normally associated with Mediterranean (specifically North African) practice.

4

Thus mercantile and cultural contact was fairly strong. The Roman Empire, which was pushing west at this time, may even have viewed western Britain as simply a semidetached part of the Roman domain. Yet by the second half of the sixth century, Tintagel was substantially deserted. Almost certainly the culprit was the plague. The date fits, and the opportunities there for contact with the disease were probably the greatest in Britain.

A second mainland British entry point for the plague was probably the small town of Cadbury Congresbury on the river Yeo in Somerset. Excavations there have, as at Tintagel, produced evidence of trade with the Mediterranean. Fragments of wine amphoras from southern Greece, fine plates from western Turkey and North Africa, and olive oil amphoras from southern Turkey have been unearthed on the site. All date from the first half of the sixth century

A

.

D

.—and again, during the second half of the century, the site became deserted.

Additional British Isles entry points for plague rats may have included a coastal settlement north of Dublin called Lough Shinney, which ceased to exist in or immediately after the mid–sixth century; the fortress of Garranes near Cork, which also ceased to function then;

5

the north Welsh coastal site of Deganwy, a probable fifth- or sixth-century royal center associated with the known royal plague victim, King Maelgwn; and, also in Wales, the Porthmadog/Borth-y-gest area at the northeast corner of Cardigan Bay.

This last probable entry point is of particular importance because it is through the Porthmadog area that the great citadel of Dinas Emrys, ten miles farther north, would have been infected with plague. Dinas Emrys was abandoned in the mid–sixth century, like so many other British sites. The evidence for Mediterranean trade at Dinas Emrys is nowhere near as great as at the other sites, but excavations have yielded a fragment of west Turkish amphora and a shard of French-made plate (decorated with a Christian chi rho symbol).

After arriving in Britain through one or more of these entry points, the plague almost certainly proceeded to devastate vast areas of the southwest and Wales. Archaeology has revealed that at the very time the plague would have been raging, many settlements became totally depopulated, presumably as a direct result of the epidemic.

In Cornwall, a mile from the Atlantic coast, a settlement now known as Chun, with its twenty-foot-thick, twelve-foot-high stone defenses, became a ghost town in the mid–sixth century. It had likely been involved in the mining and export of tin and had therefore probably been in direct contact with overseas traders. A somewhat larger fortified Cornish settlement, Killibury, with a population of perhaps two hundred to three hundred, appears also to have become depopulated at the same time, as did a village at a site now called Grambla, near St. Ives.

In Devon, High Peak—a small fortified town, now a deserted series of earthworks on a windblown cliff top—ceased to exist after flourishing for more than seven hundred years. Another Devon coastal settlement, Mothecombe, also appears to have fallen into oblivion in the mid–sixth century. Dozens of other settlements almost certainly suffered the same fate but have not yet been detected archaeologically.

As well as those settlements that appear to have vanished into oblivion at the time of the plague, several other major archaeological sites have yielded fascinating evidence of rapid change or drastic population reduction at that time. The most important is the ancient Roman city of Viroconium (Wroxeter), which appears to have suffered a major drop in population followed by a complete reordering of the city’s property boundaries.

6

The evidence from the site suggests that in the mid–sixth century the city’s major market fell into disuse, presumably because of a reduction in trade and number of customers.

7

Within a few decades this was followed by a complete redesign of the city’s property boundaries within the much reduced urban area, and on the site of the marketplace a local magnate decided to build a large private house. This disrespect for previous property boundaries and former public property strongly indicates a substantial demographic discontinuity occurring at around the time of the plague.

On the eve of the plague, the city probably boasted several thousand inhabitants, spread over nearly two hundred acres and defended by almost two miles of timber palisade atop a substantial earthwork. It also likely had several churches, one of which has been recently discovered by archaeologists using ground-penetrating radar. But a few decades after the plague, the city was a very different place. It had shrunk to around twenty-five acres, its defenses were adjusted accordingly, and dozens of new houses were constructed on property plots that apparently did not respect their pre-plague predecessors. In part of the old Roman public baths (next to what had been the market) the inhabitants of a large new private house built a private chapel, the remains of which still survive today.

8

I

t is likely that the plague recurred several times in the sixth century and that the cumulative result of the disease (together with the famine which preceded it) was a population reduction of up to 60 percent in southwest Britain (what is now southwest England, Wales, and the West Midlands).

9

No figures survive (and probably none were ever gathered) for the number of people who died of plague during that time. The only clues to the likely mortality rate are the much-better-recorded experiences of the fourteenth-century visitation of the plague (the Black Death), indications of the sixth-century plague mortality rates in the eastern Mediterranean, and the evidence for settlement discontinuity in sixth-century southwest Britain. It is also quite possible that in northern Europe, including southwest Britain, the disease was transmitted even more easily and more rapidly than in the warmer, drier south of the Continent. Plague bacteria survived for many hours in damp climates, compared to just a few minutes in the drier Mediterranean region. Both dry and damp regions would have suffered from flea bite–disseminated infection, but Britain would have been more vulnerable to infection caused by air-carried bacteria, which could be directly inhaled without the need for flea-bite transmission.

With up to 60 percent of the population dead in southwest Britain (perhaps up to 90 percent in some areas if typical plague devastation patterns pertained), normal life virtually collapsed, much agricultural land went out of use, and—as the archaeological record testifies—many towns and villages became depopulated and deserted.

With such devastation, the question must be asked: Why does there seem to have been no folk memory of this catastrophe?

The answer is that there may well have been.

T H E W A S T E L A N D

C

ontrary to received wisdom, the sixth-century plague catastrophe may indeed have been preserved in the oral tradition and in literature that, centuries later, acted as source material for particular aspects of the medieval Arthurian romances—especially those associated with the quest for the Holy Grail.

The concept of the “Waste Land” occurs in at least half a dozen Arthurian romances dating from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries.¹ It also occurs in a totally non-Arthurian, mid-eleventh-century Welsh epic called the

Mabinogi

and possibly in the twelfth-century

History of the Kings

of Britain,

by Geoffrey of Monmouth.² In several of the romances the phenomenon is specifically referred to as the “Waste Land,” while in several others—and in the

Mabinogi

—the concept is manifestly in evidence but is not given a formal name.

Three key pieces of circumstantial evidence suggest that the Waste Land concept may derive in part from the real sixth-century catastrophe. For one thing, there is the similarity of date. All but two of the stories involving the concept of the Waste Land are in works associated with the semilegendary Dark Age

dux bellorum

(warlord) Arthur, who is said to have died in either 537 or 542; the mid-tenth-century

Annales Cambriae

(The Welsh Annals)

gives the former date, the twelfth-century

History of the

Kings of Britain

the latter. Certainly the

History of the Kings of Britain

(and quite possibly other now long-lost texts) would have been known to the writers of the Arthurian romances, who would therefore have been well acquainted with Arthur’s sixth-century vintage.

Additionally, there are similarities in the nature of the literary and real “Waste Land” catastrophes.

The Welsh Annals

actually refer to the 530s famine in the very same sentence in which the death of Arthur is recorded; the entry for 537 calls it a

“mortalitas”

(mass death) that took place in Britain and Ireland. This

mortalitas

is almost certainly the same event as the “failure of bread” (the famine) referred to in the

Annals of Ul

ster

for the years 536 and/or 538.³