Catherine the Great (41 page)

Read Catherine the Great Online

Authors: Simon Dixon

Boisterous in private, discreet and demure in public, the young Grand Duchess Catherine set out on her arrival at the Russian Court ‘to please the grand duke, to please the empress, and to please the nation’.

The young Grand Duchess Catherine soon after her marriage, after Grooth

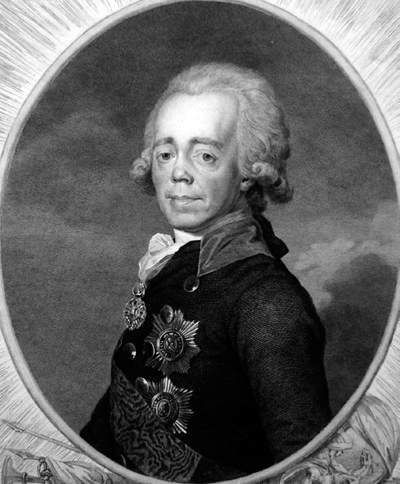

Few eighteenth-century princes escaped unscathed at the hands of second-rate artists. Peter III was no exception. The Synodal painter Aleksey Antropov captured something of the fabled vacuity of Catherine’s ill-fated husband.

Peter III, engraving after A. P. Antropov

While the empress’s memoirs implied that Paul I was the progeny of Sergey Saltykov, her son always regarded Peter III as his father and resembled him strongly in both personality and physique.

Paul I, English engraving of the 1790s

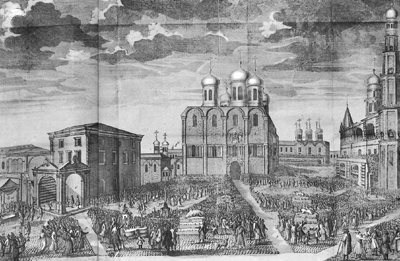

Modelling his illustrations of Catherine’s coronation on those of the French kings at Reims, Jean-Louis de Veilly transformed the intimate interior of the Cathedral of the Dormition into a cavernous temple.

Catherine’s coronation: nineteenth-century engraving after J. L. de Veilly

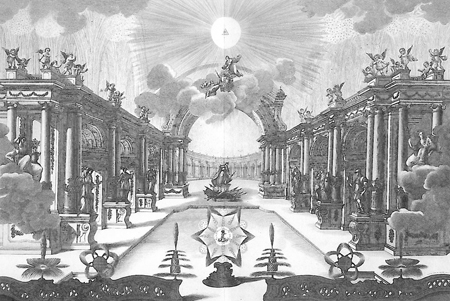

Elaborate allegorical fireworks were one feature of Baroque Court culture that remained central to Russian ceremonials throughout Catherine’s reign. This display, performed on the banks of the Moscow River opposite the Kremlin on 29 September 1762, was intended to confer dynastic legitimacy on a newly-crowned usurper.

Coronation fireworks, 1762: A. K. Melnikov from an engraving by E. G. Yinogradov

Elizabeth’s coronation in 1742 served as the model for Catherine’s twenty years later. In a scene facing north towards the Cathedral of the Dormition, the cockaigne for the populace on the Kremlin’s Cathedral Square is flanked by the Red Staircase and the Ivan the Great bell-tower. Such feasts were still staged in the 1790s, though by then they had long been dismissed as barbaric by Western visitors to Russia.

Elizabeth’s coronation feast in the Kremlin Square, 1742: engraving of 1744

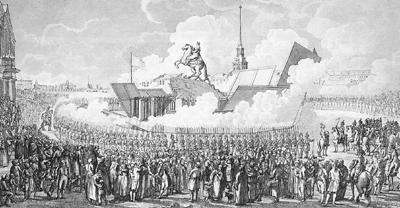

‘From Catherine II to Peter I’ was the lapidary motto chosen by Falconet for his statue of the empress’s most glorious predecessor. On 7 August 1782 she witnessed the unveiling of the first public monument in Russia from the balcony of the former Bestuzhev mansion on the left of the engraving.

The unveiling of Falconet’s monument to Peter the Great: engraving by A. K. Lemnikov after A. P. Davydov, 1782

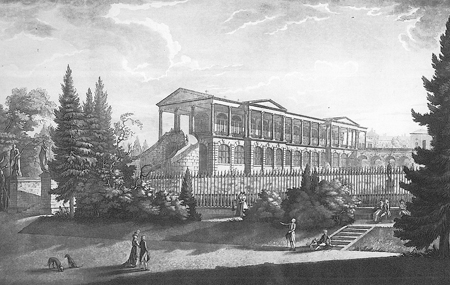

‘Apart from seven rooms garnished in jasper, agate, and real and artificial marble, and a garden right at the door of my apartments, I have an immense colonnade which also leads to this garden and which ends in a flight of stairs leading straight to the lake. So, search for me after that, if you can!’

The Cameron Gallery, Tsarskoye Selo: aquatint engraving by J. G. de Mayr, 1793

Though Catherine sought to surpass rather than merely imitate Peter I, her declared intention to complete what he had begun was part of her spurious claim to legitimacy. Tsar Peter gazes down approvingly from the heavens in Ferdinand de Meys’s allegorical representation of the empress’s great journey to the South in 1787.

Catherine’s journey to the south, 1787: allegorical engraving by Ferdinand de Meys, courtesy of Dr James Cutshall

The first pornographic British caricature of the empress appeared less than two months after Caroline Walker’s majestic engraving, done at the outset of the Russo-Turkish War in 1787 from the copy of Alexander Roslin’s portrait owned by Catherine’s ambassador to London, Count Semën Vorontsov.

Catherine II, engraving by Caroline Walker after Roslin, London, 1787

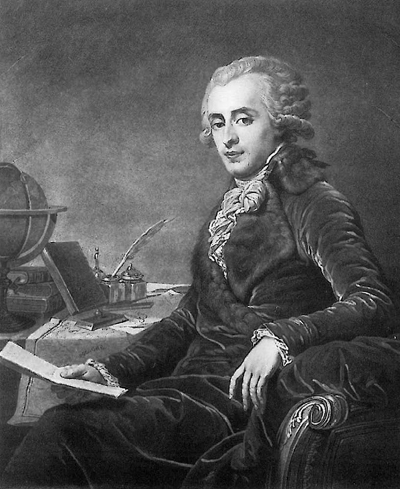

Though Platon Zubov liked to pose as a worthy successor to Potëmkin, he was in reality an arrogant upstart who damaged the empress’s reputation in her declining years. This version of Lampi’s portrait was done by the British engraver, James Walker, resident in Russia between 1784 and 1802.

Prince Platon Zubov, engraving by James Walker after Lampi, St Petersburg, 1798