Catilina's Riddle

Authors: Steven Saylor

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Historical, #ISBN 0-312-09763-8, #Steven Saylor - Roma Sub Rosa Series 03 - Catilina's Riddle

CATILINA'S RIDDLE

C A T I L I N A ' S R I D D L E .

Copyright © 1993 by Steven Saylor. Map copyright © 1993 by Steven Saylor. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any

manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in

critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New

York, N. Y. 10010.

Production Editor:

David Stanford Burr

Design:

Judith A.

Stagnitto

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Saylor, Steven.

Catilina's riddle / Steven Saylor.

ISBN 0-312-09763-8

1. Rome—History—Conspiracy of Catiline, 65-62 B. C. —Fiction.

2. Cicero, Marcus Tullius—Fiction. I. Title.

813'. 54—dc20 93-24282

First Edition: September 1993

1 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the Shade of My Mother

N O M E N C L A T U R A

The Latin name Catilina is sometimes spelled Catiline, especially in older texts, just as the Latin Pompeius is more familiarly rendered Pompey and Marcus Antonius becomes Mark Antony. Scholars nowadays tend to prefer original Latin spellings, which I have followed in the case of Catilina, if only for its euphony. The stress falls on the third syllable, which has a long i.

I have also used contemporary Latin names for a number of cities.

Some of these (with their more familiar names) include: Faesulae (Fie-sole), Arretium (Arezzo), Massilia (Marseille), and Florentia (Florence).

Dates are given according to the Roman calendar before it was reformed by Julius Caesar. These are the months of the year (with English names and spellings, if different, in parentheses, along with their number of days): Januarius (January, 29 days), Februarius (February, 28 days), Martius (March, 31 days), Aprilis (April, 29 days), Maius (May, 31

days), Junius (June, 29 days), Quinctilis (July, 31 days), Sextilis (August, 29 days), September (29 days), October (31 days), November (29 days), and December (29 days).

The Romans did not reckon the days of the months by consecutive numbers, as we do, but by their positions in relation to certain nodal days, namely the Kalends (the first day of the month), the Nones (the fifth or seventh day), and the Ides (the thirteenth or fifteenth day). The day of the month was reckoned by counting backward from these days.

I have tried to conform to this system in most cases.

The story begins on the first day of June (the Kalends of Junius), 63 B. C.

Embossed upon the shield Aeneas saw

T h e stony halls of the netherworld, the domain of the damned

A n d the punishments they suffer. There Catilina clings to the edge of a sheer

Precipice, cringing in terror while the Furies beat their wings about h i m . . .

V I R G I L ,

The Aeneid,

VIII: 666-669

How haue we chang'd, and come about

in euery doome,

Since wicked C A T I L I N E went out,

A n d quitted Rome?

O n e while, we thought him innocent;

And, then w'accus'd

T h e Consul, for his malice spent;

A n d power abus'd.

Since, that we heare, he is in armes,

We thinke not so:

Yet charge the Consul, with our harmes,

So, in our censure of the state,

We still do wander;

A n d make the carefull magistrate

T h e marke of slander.

B E N J O N S O N ,

Catiline

his Conspiracy,

A C T I V

: 863-878

What is truth?

P O N T I U S P I L A T U S

The

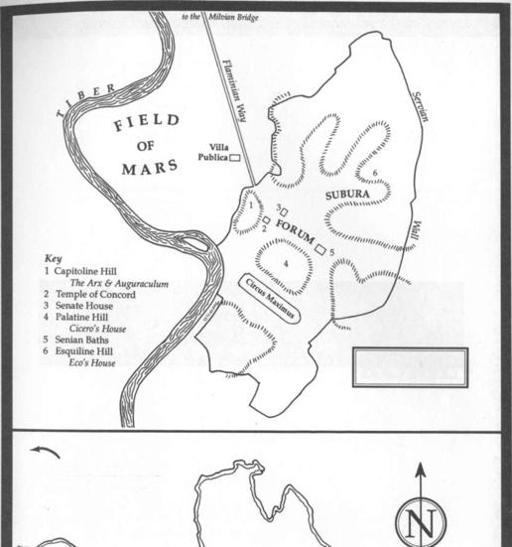

CLAUDIAN ESTATES

in Etruria, together with maps of

Rome & Northern Italy at the time of

Cicero's Consulship, 63 B.C.

ROME

to

GALLIA NARBONENSIS

(home of the Allobroges)

P A R T O N E

NEMO

C H A P T E R O N E

ccording to C a t o . . . " I said, and paused, squinting at the scroll. Bright summer sunlight from the window glared A across the parchment, obscuring the faded black letters.

Then again, at forty-seven, my eyes are not what they used to be. I can count the leaves on an olive tree fifty feet away, but the difference between O and U, or even I and L, is not as clear as it once was.

"According to Cato, " I began again, holding the scroll at arm's length and reading silently. "Well, this is ridiculous! Cato clearly says that the haymaking should have been done by now, yet here it is, the Kalends of Junius, and we haven't even begun!"

"If I may interject, M a s t e r . . . " Aratus, standing at my elbow, cleared his throat. He was a slave, not yet fifty, and had been foreman of the farm since long before my arrival the previous autumn.

"Yes?"

"Master, the blooms are not yet off the grass. It is not uncommon for the crop to be late. Why, last year it was just the same. We didn't harvest the hay until almost the end of Junius—"

"And I saw how much of it went bad in the barn! Bundles and bundles rotted away during the winter, so there was hardly enough left to feed the oxen during the plowing this spring. "

"But that was because of the storm damage to the roof of the barn last winter, which let in the rain and so spoiled much of the hay. It had nothing to do with the late harvest last summer. " Aratus lowered his eyes and compressed his lips. His patience was near its end, if his subservience was not.

"Still, Cato is explicit: 'Cut the grass crop when the time comes,

- 3 -

and

take care that you are not too late

in cutting it.' Now, Marcus Porcius Cato may have been dead for almost a hundred years, but I don't suppose the ways of nature have changed in that time." I looked up at Aratus, who pursed his lips tightly.

"And another thing . . ." I shifted through the scroll, seeking the passage that had leaped out at me the night before. "Ah, here: 'The chickpea is poisonous to livestock and thus should be pulled up when found growing among the grain.' And yet, only the other day, I saw one of the slaves take the burnt portions of chickpeas from the kitchen and mix them in among the oxen's feed."

Did I catch Aratus rolling his eyes, or only imagine it? "The

herbage

of the chickpea is poisonous to livestock, Master, not the bean. Poisonous to men, as well, I suspect," he added dryly.

"Ah, well. Yes, that explains it then." I closed my eyes and pinched the bridge of my nose. "As you say, if the bloom is not yet off the grass, I suppose we shall simply have to wait to begin the haymaking. The vineyard has begun to come out in leaf?"

"Yes, Master. We have already begun to trim the vines and tie them to supports—just as

Cato

says to do. And since, as

Cato

advises, only the most skilled and experienced slaves should be engaged in the task, perhaps I should go and oversee the work."

I nodded, and he left.

The room seemed suddenly stuffy and hot, though the hour was not quite noon. I felt a throbbing in my temples and told myself it was the heat, though it was more likely from squinting at the scroll and arguing with Aratus. I walked out into the herb garden, where the air was cooler. From within the house I heard a sudden shriek—Diana screaming, and then Meto shouting, "I never touched her," followed by a maternal scolding from Bethesda. I sighed and kept walking, through the gate and onto the path that led to the goat pens, where two of the slaves were engaged in mending a broken fence. They scarcely looked up as I passed.

The path took me alongside the vineyards, where Aratus was already busy overseeing the tying of the young vines. 1 kept walking until I came to the olive orchard and paused in the cool shade. A bee buzzed by my head and flitted among the tree trunks. I followed it up the hillside to the edge of the orchard, to the ridge where a patch of virgin forest stood.

A few naked stumps at the periphery showed where an attempt had once been made to clear the high land, and then abandoned. I was glad the ridge had been left wild and wooded, though Cato would have advised clearing it for crops; Cato always seemed to prefer high places to the lowlands where mist might gather and ruin the crops with rust.

I sat on one of the stumps and caught my breath beneath the shade of a gnarled, ancient oak. The bee buzzed by my ear again—perhaps it

- 4 -

was drawn to the almond-scented oil that Bethesda had rubbed into my hair the night before. How gray my hair was becoming, half gray or more, mixed in with the black. Living in the countryside, I did not bother to have it cut as often as in the city, so that the loose curls lapped onto my neck and over my ears, and for the first time in my life I had grown a beard—that also was half gray, especially around the chin.