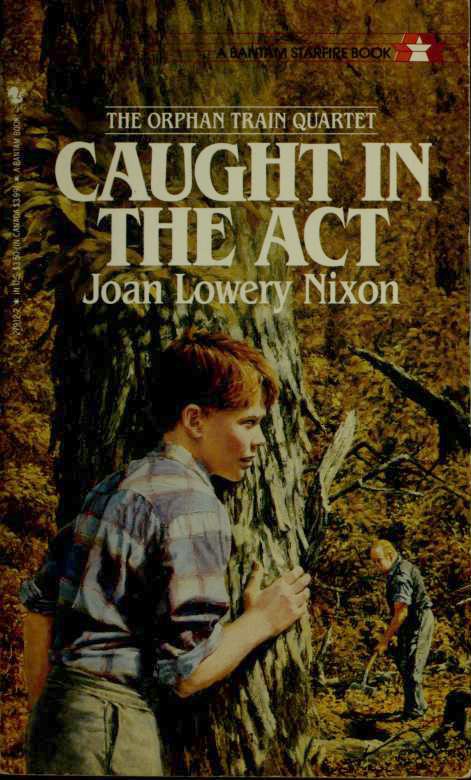

Caught in the Act

Authors: Joan Lowery Nixon

Tags: #Foster home care, #Farm life, #Orphans

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

A Note From the Author

During the years from 1854 to 1929, the Children's Aid Society, founded by Charles Loring Brace, sent more than 100,000 children on orphan trains from the slums of New York City to new homes in the West. This placing-out program was so successful that other groups, such as the New York Foundling Hospital, followed the example.

The Orphan Train Quartet was inspired by the true stories of these children; but the characters in the series, their adventures, and the dates of their arrival are entirely fictional. We chose St. Joseph, Missouri, between the years 1860 and 1880 as our setting in order to place our characters in one of the most exciting periods of American history. As for the historical figures who enter these stories—^they very well could have been at the places described at the proper times to touch the lives of the children who came west on the orphan trains.

Vt>TU^ ^^^^w<^ yyyy<^,^

f-

A number of the CHILDREN brought from WEW YORK ara still without homes.

KRIKttM KMIIM Ti!R <'«>r.>TIIV I'l RAMR

^ASsI, AND SEE THE2KC.

MERCHANTS, FARMERS

AND FRIENDS GENERALLY A re req*.i08ted to give publicity to the above

AxJt Mrcii.oai.iaE,

Jennifer Collins hurried to the screened-in porch of Grandma Briley's home. She dropped into a comfortable wicker chair next to Grandma's and picked up the journal which had been written so long ago by FYances Mary Kelly. Tucked inside was the photograph of the girl with the long, dark hair who might almost have been Jennifer herself, if the old-fashioned dress and hair twisted into a soft bun hadn't given her away. Jennifer took the picture out and studied it again.

It was hard to think of the young woman in the sepia-toned picture as her great-great-great grandmother. Grandma had told Jennifer and Jeff that Frances had been eighteen when this photograph was taken. "Only three years older than I am now," Jennifer murmured.

A noise behind her startled Jennifer. She turned to see her twelve-year-old brother Jeff appear in the doorway cautiously balancing three glasses and a frosted pitcher of lemonade on a tray. He handed them over to

1

Grandma with a sigh of relief before he dropped into the nearest chair.

"Grandma's going to tell us Mike's story now," Jennifer told him.

Jeff glanced impatiently toward the quiet garden and mumbled, "I bet Mike had a lot of adventures after he went out West with the orphan train. I bet he got to do all kinds of exciting stuff—all the things I would have done if Fd been there."

He leaned over the arm of his chair toward Grandma. "Did Mike get to be a cowboy? Did he ever fight renegade Indians? Or get into a shootout with outlaws?"

"Be quiet, Jeff," Jennifer said. "Grandma, you told us that Mike suspected the man who adopted him of committing a murder, and I want to know what really happened."

Grandma laughed as she held up her hand. "You're both getting ahead of the story. Just be patient, listen, and you'll know all I know. Til read from the opening of Mary's journal before I begin Mike's story." Grandma took the journal from Jennifer, opened it, and began to read.

As long as I live I shall never forget the misery and fear on Mike's face a^ he sat on the platform in that little church in St Joseph, facing the people who had come to see the children from the Orphan Train,

Mr, Crandon, who had been so shocked and angry when he found out that Mike had been a copper stealer back in New York City, was moving from group to group, leaning close to whisper. Each couple to whom he spoke would immediately dart a glance toward Mike, some of them frowning, some staring with suspicioTL

I wanted to cry out, "Don't listen to Mr, Crandon! Mike is a good boy. He didn't mean to do wrong. He

was so desperate to help feed our family^ he just didn't think.'' But I couldn't speak out against Mr, Crandon. He wa^ a successful businessman^ well thought of in St Joe; and we were strangers, orphans brought here from New York in the hope that some kindhearted people would offer us homes.

There was nothing I could do.

I thought about U.S. Army Captain Joshua Taylor, whom we had met on the orphan train. He had liked Mike. He'd praised Mike for his bravery. Oh, why couldn't someone as fine as the Captain have offered Mike a home? My heart ached as I saw Mike chosen by the Friedrichs. Mr. Friedrich seemed harsh and humorless, and I suspected that his only reason for adopting an Orphan Train child was to have an unpaid hired hand.

I hugged Mike tightly as we parted, hating to let him go, terrified of what might be in store for him.

Michael Patrick Kelly sat by himself in the wagon bed behind the Friedrich family, grabbing the side for support each time the wheels dropped in and out of the ruts and gullies in the dirt road. The first time the wagon lurched, Mike sprawled on his back with a yelp, and Gunter Friedrich—squeezed on the front seat between his parents—^turned to look at him with a mocking laugh.

Mike hated to be the laughing stock, and he was beginning to dislike Gunter heartily. The next time the wagon bounced so hard that it sl^^ped his backside, Mike met Gunter's stare by puffing out his cheeks and arching his back so that his stomach protruded. Gun-ter's eyes narrowed, and he whirled around to face forward. Mike settled back, hoping he wouldn't be bothered by Gunter again on this trip.

He had wished for a loving family and—even thou^ no one would ever replace his best friend and brother Danny—^he'd imagined there'd be a boy close to his age

who'd become his chum. Mike sighed. No such luck with Gimter.

The Friedrichs were not the kind of family Mike had pictured when Mr. MacNair and Mrs. Banks had described the new lives the Orphan Train children would lead in the West.

Hans Friedrich was balding and heavy. Mike shuddered as he remembered his first sight of Mr. Friedrich. His rounded stomach bulging from underneath his vest, his jowls quivering, he pointed at Mike and demanded of Andrew MacNair, the scout who found towns that would take the children, "That boy. We want him."

Mrs. Friedrich's head bobbed up and down eagerly. Her nose was like a round button in her rosy face, and her eyes were clear and blue, crinkled at the edges by her shy snule. But she flinched as her husband growled at her, "It's your fault we are late, Irma. Because of you, we missed getting a bigger, stronger boy. This boy is only what? Nine? Ten?"

"Eleven!" Mike said, insulted at the guess and earnestly wishing he weren't so small for his age.

Mrs. Friedrich tugged her shawl more tightly around her shoulders and stammered, "Th-the boy needs only some good food to make him grow tall and strong. Why, in no time he'll be like—like Gunter." She patted her son's arm, but Gunter shook her hand away.

Mike glanced at Gunter. He knew inunediately that he had no desire to be anything at all like Gunter, who was fat and pasty, with hair so blond it was almost white. Gunter's expression was sullen. Mike wondered if he ever smiled. His thick lips were twisted into a pout. At the mention of his name, he scowled at the floor, kicking at an invisible spot with the toe of one shoe.

Obviously trying to make amends, Mrs. Friedrich snuled and said, "How fine it wiU be to have another boy in the house. He will be like a brother to you, Gunter."

"Don't want a new brother!" Gunter mumbled. "Brothers only cause trouble."

"Now, now." Mrs. Friedrich sniiled nervously. "Soon the two of you will be the best of friends."

"Oh, no, we won't," Gunter hissed, his voice so low that Mike wondered if he were the only one who had heard him.

As soon as Andrew left Mike and the Friedrichs to get acquainted, Mr. Friedrich folded his arms across his chest, frowned at Mike, and said in a stem, loud voice, "So. You were a pickpocket. A thief."

Mike cringed as people nearby turned to stare at him. "Well, yes, I was. But I promised my mother and myself that I would never steal again," he replied. "I hope you'll believe me."

"I believe you," Mr. Friedrich answered, "because if you steal again, you will be beaten. You won't like the beatings, so you won't steal." The comers of his mouth tilted upward smugly. "I know now how to handle boys like you."

"Oh!" Mrs. Friedrich gasped. As she shot a quick glance at her husband, Mike noticed a fearful look in her eyes.

Gunter snickered and grinned a wicked grin. Mike's face grew hot with embarrassment. He wished he could punch Gunter right in his puffy, round nose. He wondered how old Gunter was. Maybe thirteen? Fourteen? He was taller and much heavier than Mike. Mike quickly decided that punching Gunter might not be a very good idea. After all, Gunter was part of his new family. And Mike usually got along with everyone he met, so he was surprised at his immediate dislike of Gunter. He decided to try and control his bad first impression.

Now, as he sat in the wagon bed, Mike thought about the bullies he'd known and had run-ins with in New York City. He had never let one of them get the best of him, and there was no way he was going to let Gunter get him down.

He looked around the landscape as the wagon plodded on, and his good spirits began to return. Low, rolling hills, many of them scattered with stalks and remnants of crops, a few still thick with high grain, some fragrant with the earthy smell of newly turned soil, stretched out around him. Golden-leaved trees were interspersed with deep green pines, and behind a wooden-rail fence Mike spotted a neat, small garden bursting with tangled vines and pumpkins larger than those he'd seen in the city's greengrocers' stalls.

Until he had left New York City on the Orphan Train, Mike had never seen open country. He missed the bustle and action of the city streets, but he supposed this quiet land might have something to recommend it, too. He wished it offered more excitement for a boy his age. He wished he were sixteen instead of eleven, so he could ride for the pony express. Galloping his horse through heat and snow, racing from whooping hordes of Indians to save the mail—wouldn't that be a grand way to live! Faster! Faster! With the way station just ahead! He'd leap from his horse, slap the saddlebags across a fresh mount, and jump into the saddle. Nothing would stop him! He reached to tug an arrow from his shoulder—

Mike sighed and shifted away from the long splinter in the side board that was digging into his back. Maybe he'd like working on a farm. He had promised Ma he was going to work hard and do his best.

A sudden wave of loneliness, so strong that it caused him to shiver, brought Ma's face to his mind, and he could see the terrible sorrow in her eyes. FU make you proud of me yet, Ma, he vowed.

Mike glanced toward the front seat of the wagon and noticed Mr. Friedrich again scowling at his wife. He couldn't hear what was being said, but it sounded like the growl and snap of a mean, hungry dog. Mike hated to admit it to himself but Mr. Friedrich frightened him. Mrs. Friedrich wasn't so bad, so who knew? Maybe, if he minded his manners and did his work well, he might get along with both just fine. Maybe all the Friedrichs—even Gunter—would turn out to be better than he had first thought them.

Mike stared up at their rounded backs. The three of them were packed as closely together on the wagon seat as sausages in a crate. Before he knew it, his mind was racing with the words for a ditty: "Three fat sausages, Gunter in the middle; fry them on a griddle with a hey diddle diddle." Pleased with his rhyme, Mike grinned to himself. Some day he'd sing his song to his sister Frances. Wouldn't she get a good laugh from it!

Mike pictured his older sister at their parting. She'd cut her long, dark hair with his penknife after she'd heard that some families might take two boys. She had posed as a boy, desperately hoping to keep their youngest brother Petey with her, and her ruse had succeeded. Thinking they were adopting brothers, a family had chosen Frances and Petey together.

Would Mike ever see Frances again? Pushing away the thoughts that caused his throat to tighten with pain, he stretched out in the wagon and laid his head on his arms. Over and over he sang the new ditty to himself until he fell asleep.

"Hush! He will hear you, Hans!"

"He won't hear anything. He's sleeping."