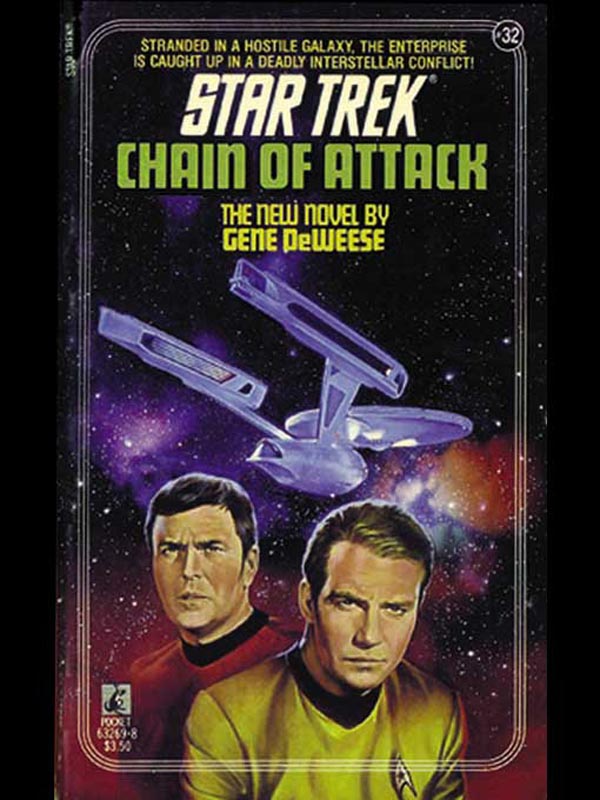

Chain of Attack

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

An

Original

Publication of POCKET BOOKS

POCKET BOOKS, a division of Simon & Schuster Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com/st

http://www.startrek.com

Copyright © 1987 by Paramount Pictures. All Rights Reserved.

STAR TREK is a Registered Trademark of Paramount Pictures.

This book is published by Pocket Books, a division of Simon & Schuster Inc, under exclusive license from Paramount Pictures.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020

ISBN: 0-7434-1983-9

POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Look for STAR TREK fiction from Pocket Books

For Juanita Coulson,

whose talent and persistence

opened the door for serendipity.

It's been a long timeâ¦

I first saw

Star Trek

when Gene Roddenberry apologetically introduced the two pilot episodes to a few hundred science fiction fans at the Cleveland World SF Convention a few days before the first program was broadcast.

Subsequently, I watched every episode that was aired and managed to talk about fifty friends and strangers into sending protest letters during the first "Save

Star Trek

" letter-writing campaign.

Over the years, it's gotten ever harder to resist the temptation to watch the reruns, particularly when they're showing gems like the Gary Seven episode, "Assignment: Earth," and "The Menagerie."

And nowâ

Well, I can only say it's been great fun these last few weeks, finally having an excuse to indulge myself in an episode a day, ostensibly for "research," and getting paid for it to boot.

Â

ACCORDING TO EVEN the most conservative estimates, the Milky Way galaxy contains more than one hundred billion stars, and there are at least that many other galaxies beyond our own, beyond the reach even of warp drive. This means that for every human alive on earth at the end of the twentieth century there are twenty or more stars in our home galaxy alone, and countless billions more are spread throughout the clusters and superclusters of other galaxies, stretching to the very edge of the universeâif, indeed, an edge exists. It is therefore little wonder that, even with Federation, Romulan, and Klingon ships spreading throughout space at unprecedented rates, more than ninety-nine percent of even that one galaxy is unknown and untouched by humanâor Romulan or Klingonâsensor probe. Even within the territory covered by the Federation Exploration Treaty, the unknown far outweighs the known as scout ships leapfrog over thousands of star systems in their rush to explore, to reach new horizons.

Under such circumstances, then, it is easy to go where no man has gone before. It is, in fact, often unavoidable. To survive such explorations and to return safelyâthat is another matter altogether.

"I fail to see the humor in the situation, Dr. McCoy."

As always, Spock's remark held neither anger nor resentment. It was simply a statement of fact, edged with the faint touch of bemused bafflement that was always present when the Vulcan science officer was dealing with less-than-logical humans.

"I know, Spock, I know," McCoy said, stepping back to give Spock ample room as the Vulcan's long, powerful fingers continued to methodically work the science station controls. "But you don't mind if we humans indulge in a good laugh now and then, do you?"

"Of course I do not mind," Spock said, most of his attention still devoted to analyzing the station's readouts for some sign of the probe that had been launched more than five minutes before. It was rapidly becoming apparent, however, that the probe was not going to reappear, either five parsecs away or five hundred, all of which struck McCoy as a fitting and somewhat amusing climax to the totally erratic behavior of the previous forty-odd probes.

"In fact, Doctor," Spock went on, still not taking his eyes from his instruments, "as you yourself have pointed out, such outbursts often seem to have a therapeutic effect on your species. It would hardly be logical for me to wish to deny you something that could improve your physical and mental well-being and hence your efficiency in performing your duties."

McCoy chuckled, still watching the display screens over Spock's shoulder. "Maybe it's just as well you

don't

ever laugh, Spock. You're already too blasted efficient. I'd hate to see what would happen if you ever developed a sense of humor. Jim and I and half the crew would only be excess baggage."

"Another example of human humor, I assume, Doctor. I find it difficult to believe that even you would look favorably on inefficiency. But if I may be allowed toâ"

A shudder rippled through the

Enterprise

, momentarily shifting the deck beneath their feet. Spock, rock steady despite the movement, called up a dozen new displays on the screens.

"Another shift in field strength, Captain," he said, "an increase of twenty-seven-point-one-six percent. I would suggest drawing back approximately ten A.U. as a precautionary measure."

"Take us back ten A.U., Mr. Sulu, warp factor three," Kirk said without hesitation. He had long since learned not to question his first officer's suggestions. "Hold steady at that position."

"Done, sir," the helmsman said, his fingers already entering the commands into his console.

McCoy, silent now as he gripped the padded handrail to steady himself, turned toward Kirk. Seated in the command chair, the captain was intent on the forward viewscreen, where the flowing ribbon of the Sagittarius arm of the galaxy overlay the distant turbulence of the Shapley Center. As they watched, the star field rippled briefly, much as the bridge itself had seemed to ripple a moment before.

"Another change in the field strength, Mr. Spock, or just the result of our motion in the field?"

"Our motion, Captain, with respect to the irregularities near the anomaly itself. The field remains steady at its new level."

"And the last probe, the one whose disappearance Dr. McCoy found so amusingâstill no sign of it?"

"None, Captain."

"A malfunction in the probe itself, perhaps?"

"Unlikely, Captain. As you know, the probes are little more than powerful subspace beacons attached to impulse engines. Considering the simplicity of their design and construction, the likelihood of any vital component failing has been statistically established to be less than one in one-point-three million."

"But it is possible," Kirk persisted.

"Possible, yes, Captain, in the same sense that anything, no matter how unlikely, is statistically possible."

"Point taken. What other explanations can you suggest?"

"The most likely is that the probe is beyond the range at which it can be detected."

Kirk swung his chair to look directly at the science officer. "Out of range, Mr. Spock? I was given to understand that their signals could be picked up at a range of more than five thousand parsecs."

"Five thousand four hundred eighty, to be precise, Captain, though that is, of course, only the minimum guaranteed range."

"You're saying thisâthis 'gravitational anomaly' could have transported the probe more than five thousand parsecs?"

"Obviously, Captain."

"But none of the other probes has reappeared at any distance greater than five

hundred

parsecs."

"Affirmative, Captain."

"That's it, Spock? No elaboration?"

"If you wish, Captain. As you and Dr. McCoy are certainly aware, we have been unable to establish any logical pattern based on the behavior of the probes sent through the so-called anomalies. Some have not been affected at all, as if for them the anomalies do not exist. Others have vanished and emerged into normal space little more than one parsec distant, while still others have reappeared nearly five hundred parsecs away in a totally different direction. There is therefore no logical reason to assume that the range is limited in any way. The distance a probe is transported is apparently not related in any way to its entry velocity. It is more likely a result of the geometry of space itself and the manner in which it is distorted by these socalled anomalies, and that distortion appears to vary randomly from moment to moment, even to cease entirely on occasion."

"From your repeated use of the phrase 'so-called anomalies,' can I assume that your observations have suggested a more useful or more accurate term?"

"Not at all, Captain. It is only that I am beginning to doubt that these objects are indeed something as simple as anomalies resulting from surrounding areas of gravitational turbulence."

"What, then?"

"I do not know, Captain."

"But you must have some thoughts on the subject, Spock."

"Of course, Captain."

"And those thoughts are�" Kirk prompted.

"I can only say, Captain, that there is a distinct but unquantifiable possibility that they are not natural phenomena at all."

In the silence that followed, all eyes on the bridge turned to Spock. Then a short burst of laughter came from McCoy.

"An unquantifiable possibility?" McCoy said, shaking his head in mock surprise. "That isn't your Vulcan way of saying you have a hunch, is it, Spock?"

"It is hardly a hunch, as you chose to call it, Doctor. It is merely that the results of our observations so far appear totally random and therefore illogical. Past experience has led me to conclude that phenomena which appear to be illogical are less often the result of natural laws than they are the result of manipulation of those laws by intelligent but less-than-logical beings."

Captain James T. Kirk suppressed a smile as he nodded and shifted to a more comfortable position in the command chair. The thought that the anomalies were not natural phenomena had, of course, occurred to him, but, as Spock would say, he had not assigned it a high probability factor. For one thing, when the

Enterprise

had first run into one of the anomaliesârun into it quite literallyâthe ship had been instantaneously transported more than three hundred parsecs and damaged by the effects of the surrounding turbulence. Under those conditions, everyone's priorities had centered on survival, both their own and the

Enterprise

's, leaving little time for scientific analysis or philosophizing.

But now it was a different matter. Equipped with newly designed sensors that allowed them to precisely locateâand avoidâthe strangely complex turbulence, and supplied with more than two hundred probes, they had come to study what was apparently a cluster of such anomalies discovered by a scout ship not long after the

Enterprise

's return from the Mercanian system, where the first anomaly had deposited them so unexpectedly. Or, more accurately, they had come to study a cluster of gravitationally turbulent areas in order to determine if any or all of those areas contained at their centers the same type of anomaly that had swallowed the

Enterprise

and then spit it out three hundred parsecs away. By sending the probes through such anomalies, they had hoped to determine just where the anomalies led.

Anomalies had indeed been found in the centers of seven of the areas of turbulence so far, and forty-eight probes had been dispatched. Six had passed through the anomalies without effect, emerging on the far side with no indication of damage or change of any kind. Forty-one had reappeared at distances ranging from one to five hundred parsecs, in directions that bore no discernible correlation to anything. Two probes sent through the same anomaly within milliseconds of each other reappeared more than six hundred parsecs apart, one in the direction of the Shapley Center, the other in the general direction of Klingon territory.

In short, as Spock had said, the operation of the socalled anomalies appeared totally illogical and had thus far defied analysis. And now one of the probes had simply vanished, either transported beyond the five-thousand-parsec range of its transmitter or destroyed orâ¦

"Could the disappearance be related to the shift in the field strength, Mr. Spock? The two occurrences were fairly close together."

"It is possible, of course, Captain. Without further data, however, there is no way of confirming or denying the hypothesis."

"Another probe, then, Mr. Spock?"

The hiss of the doors to the turbolift forestalled Spock's reply. A stocky man in his fifties, his tightly curling hair beginning to gray, strode onto the bridge. His angry glower, as much as his green civilian tunic, distinguished him from the

Enterprise

personnel.

"What sort of nonsense have you been up to now, Kirk?" the man snapped, making the omission of the captain's rank sound more like an insult than an oversight.

"Welcome to the bridge, Dr. Crandall," Kirk said dryly. "What seems to be the problem?"

"The problem, Kirk, is that I was awakened only moments ago by something which, were I on a planetary surface, I would describe as an earthquake. I would like to know the cause, and I would like to know why it was not avoided, whatever it was."

Kirk turned away from Crandall toward the science officer's station. "You have the floor, Mr. Spock."

A minuscule arching of one upward-slanting eyebrow was the only change of expression as Spock turned to face Crandall. "The cause, Dr. Crandall, was an unpredicted and abrupt change in both the overall strength and the pattern of the gravitational field surrounding the so-called anomaly we are currently observing. The reason it was not avoided is that it

was

unpredicted. To the best of our knowledge at this time, such changes cannot be predicted."

Crandall, still not fully accustomed to the Vulcan's calm and rational ways, seemed to lose some of his steam.

"I see," he said. "But the shipâthe ship was not damaged?"

"Not a bit," Kirk assured him. "As you know, the new sensors allow us toâ"

"I know, I know," Crandall snapped. Then he glanced around the bridge, his eyes settling on the forward viwscreen. "There's an anomaly out there? A new one?"

"That's right," Kirk said. "The seventh."

"Why wasn't I called? I am, after all, an official observer, which would seem to me to mean that I should be present during all observations."

"If you will recall, Dr. Crandall," Kirk said quietly, "midway through our observations of the previous anomaly, you told us you didn't want to be bothered unless something unusual happened. 'Something downright spectacular,' I believe were your exact words."

"Something that can rattle the walls of a Constitution-class starship qualifies as spectacular in my book, Kirk. In any event, now that I am here, would anyone care to bring me up to date?"

"Of course, Doctor," Kirk said, turning away again. "Mr. Spock?"

"Very well, Captain," Spock said and then began a probe-by-probe account, complete with all particulars, of all observations since Crandall's hasty departure on the previous day's watch.

Kirk settled back to listen and to wonder once again what Starfleet Command had had in mind when they had allowed Dr. Jason Crandall to be attached to the

Enterprise

as an "official observer." True, Crandall had been in charge of the Starfleet-supported civilian labs that had developed the sensors that had been installed on the

Enterprise

, but Crandall himself, despite a doctorate in physics, was far more of a politician than a scientist. Otherwise he would never have been in charge of that or any other lab, Kirk was sure. And it had become abundantly clear after only a few days on the

Enterprise

that Crandall saw the labsâand this mission involving the sensors developed thereâprimarily as stepping stones to greater things, perhaps even to a seat on the Federation Science Council.