Charles Bukowski (29 page)

Authors: Howard Sounes

Faye Dunaway tried to make herself like Wanda, described in the screenplay as ‘… once quite beautiful but the drinking is beginning to have its effect: the face is fattening a bit, the slightest bit of a belly is beginning to show, and pouches are forming under her eyes.’ But the actress was still beautiful. Bukowski didn’t like her at all. In

Hollywood

, he described Chinaski’s irritation when a scene had to be rewritten so the actress playing Wanda could show off her legs.

Filming continued for six weeks, and Bukowski spent much of that time hanging around the set. Linda Lee had taken acting lessons, and was given a small part but, unlike Bukowski, didn’t make it into the final cut. David Lynch and his girlfriend, Isabella Rossellini, visited the set and chatted to Bukowski about

Eraserhead

. Helmut Newton photographed Bukowski with Faye Dunaway on his knee. Having a movie made about his life was a heady experience, and Bukowski was not so cool that he failed to get excited by it. He found himself watching the dailies and wondered aloud whether

Barfly

would win an Oscar, an institution he had once mocked in his poem, ‘Another Academy’.

While

Barfly

was being edited, yet another film adaptation of Bukowski’s work was released. Directed by Belgian film-maker Dominique Deruddere,

Crazy

Love (aka Love is a Dog From

Hell

) was premièred in Los Angeles in September, 1987. Bukowski watched it with Linda Lee and his new celebrity friends – Sean Penn and Madonna, and Elliott Gould and his wife. Although he had nothing to do with the making of the movie, and it remains an obscure art house work, Bukowski came to regard this adaptation

of three of his short stories as the most successful attempt to bring his work to the screen.

The theatrical release of

Barfly

was heralded by a publicity campaign and, for the first time in his career, Bukowski was sought after by the mainstream American media. It turned out he was a natural story for journalists: the bum they made a movie about. A question and answer session conducted by Sean Penn was given a spread in Andy Warhol’s

Interview

magazine, illustrated with pictures by the famous photographer Herb Ritts. Bukowski and Linda Lee were pictured outside their house for the

Los Angeles

Times

. Bukowski was also profiled in the gossip magazine,

People

, which ran the headline:

BOOZEHOUND POET CHARLES BUKOWSKI WRITES A

HYMN TO HIMSELF IN

BARFLY

, AND HOLLYWOOD

STARTS SINGING

The article described him as a ‘potbellied old boozer’ and the mythology of his life was embellished with the story that Linda Lee fed him thirty-five different types of vitamins to keep him alive. It amused them both because

People

was one of the low-brow publications Bukowski sometimes bought when he was shopping for beer.

He was also invited onto a number of television programs, including Johnny Carson’s

Tonight Show

, but declined them all figuring his appearances on

Apostrophes

in France should be the beginning and end of his talk show career.

The finished film was a great disappointment. Bukowski thought Mickey Rourke quite good as Chinaski, but said he’d never looked

that

scruffy; no landlord would have rented a room to him if he had. Mickey Rourke defends himself, saying he looked as Schroeder directed him to and adds, probably with an element of truth: ‘When you see yourself as you really are, sometimes that hurts.’ Linda Lee thought the film awful, and Marina didn’t think Mickey Rourke played anything that remotely resembled her father.

There was a party after the Hollywood première, with champagne served and photographers’ flash lights popping. Mickey

Rourke and Faye Dunaway congratulated Bukowski on his screenplay and reporters from the daily newspapers made a note of every slurred word he uttered. He enjoyed the attention for a while and then the booze kicked in and the scene began to seem phony. ‘I’ve got to get out of here,’ he told Linda Lee. She suggested they stay a little longer, but he was adamant. ‘This place stinks,’ he said. ‘It’s making me sick.’

The reviews in the morning papers were mixed and

Barfly

did only fair business when it opened across the United States, although it proved more popular in Europe. Yet despite the lack of box office success, and although the film is not truly representative of Bukowski’s work, it is

Barfly

more than anything that he became known for among the general public.

*

Linda Lee eventually inherited the entire estate.

A

side from almost bleeding to death when he was thirty-five, Bukowski had managed to abuse his body throughout his adult life with remarkably little ill-effect. He was certainly in bad shape – paunchy and unaccustomed to exercise, other than sporadically lifting barbells – but actual debilitating illness had not troubled him since that long ago hemorrhage after which, as he never tired of saying, the doctors warned he must never drink again. Of course, he had consumed rivers of alcohol since then. He had smoked heavily, used drugs, been beaten-up in bar fights and spent several nights in jail. And yet he did not appear significantly less healthy than most sixty-seven-year-old men.

But in the winter of 1987, following the première of

Barfly

and all the excitement and stress that went with the making of the film, Bukowski’s health began to falter. At first he thought he simply had flu, but then weeks went by without him feeling better. On 17 January, 1988, he wrote to John Martin that he’d only drunk one bottle of wine since Christmas, a sure sign he was not himself. Blood tests showed him to have been run-down throughout the previous year, but no specific illness was identified and his doctor wanted to carry out further tests. In the meantime, he was forbidden from drinking, and he had little energy for writing the novel he had recently begun,

Hollywood

, which was based on his experiences making

Barfly

.

Luckily, Bukowski and John Martin had already decided that

their next book would be a collection of early poems from obscure chapbooks and literary magazines, some dating back to the 1940s. It was published later that year as

The Roominghouse Madrigals

. As Bukowski wrote in the foreword, the poems were quite different from the anecdotal style he had developed in later years, ‘more lyrical than where I am at now’, but he did not agree with those who said the early work was better.

There was another reminder of the past when he received a telephone call from his cousin Katherine Wood, daughter of Bukowski’s happy-go-lucky Uncle John. Bukowski had gone to the trouble of mailing a German language edition of his travelogue,

Shakespeare Never Did This

, to his Aunt Eleanor in Palm Springs. She thought little of the book and gave it to Katherine, who could not make out what it was about as the text was in German. She tried to guess by looking at Michael Montfort’s photographs. ‘In almost every picture he has a bottle of wine in his hand so I thought he was a wine salesman,’ she says. When

Barfly

came out, she wondered if cousin Henry was the author and, after contacting Black Sparrow Press, she was invited to tea at San Pedro. ‘He was a little hung-over,’ she says. ‘You could see he had a pretty darn rough life with the drinking and the smoking. He wasn’t in very good shape.’

‘You probably wouldn’t like my books,’ said Bukowski, who had not seen Katherine since they were children.

Katherine agreed she probably would not. She did not want to learn about the ‘seamy side of life’.

Bukowski finished

Hollywood

late one Saturday night in the early fall of 1988, despite his poor health. It is perhaps surprising what an upbeat and funny book it is, describing a domesticated and financially secure Henry Chinaski laughing at a world crazier than anything he had experienced in the factories, bars and apartment courts of

Post Office, Factotum

and

Women

.

The following morning he awoke with a blazing fever of 103 degrees which continued for a week. He could not eat or sleep and shivered until the bed shook, convinced he was dying. The fever stopped only to return a few weeks later, and then there was another attack – three debilitating fevers in succession. His weight fell to 168 lbs.

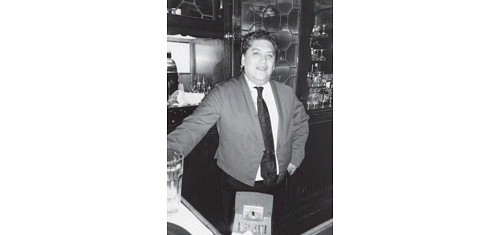

BAR LIFE

Barman Ruben Rueda who for many years served Bukowski drinks at the Musso & Frank Grill on Hollywood Boulevard. (

picture taken by Howard

Sounes

)

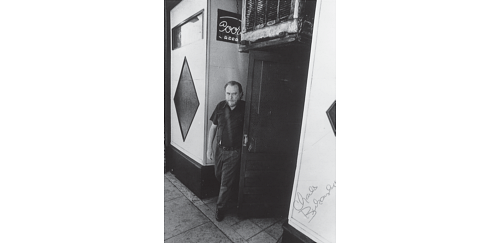

‘beer / rivers and seas of beer,’ Bukowski wrote, ‘beer is all there is.’ (

picture by Richard Robinson

.

Courtesy of Special Collections, The University of

Arizona Library. The quotation from the poem

, ‘beer’,

appears courtesy of Black Sparrow Press

)

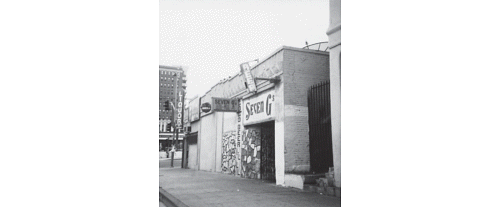

The Seven-G’s (sic) bar in downtown Los Angeles was one of the places Bukowski drank when he was living with Jane Cooney Baker and working as a shipping clerk at an art supply store. (

picture taken by Howard Sounes

)

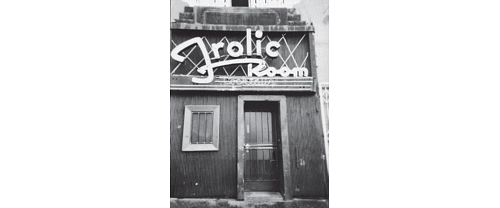

The Frolic Room on Hollywood Boulevard was a favorite bar with Bukowski in the early 1970s. (

picture taken by Howard Sounes

)

LOVE LOVE LOVE

Bukowski poses proudly, in February, 1971, with the head sculpted by Linda King and presented to him as a gift. Their love affair was at its height. When they fell out, as they regularly did, Bukowski would return the head to Linda. (

courtesy of Linda King

)

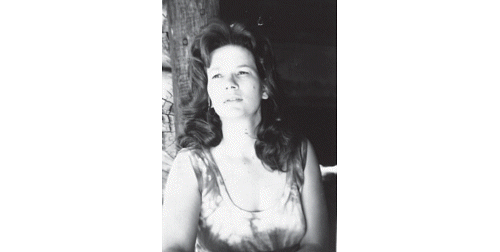

Linda King, the young sculptress Bukowski met and fell in love with in 1970 shortly after he quit his post offi ce job. (

courtesy of Linda King

)

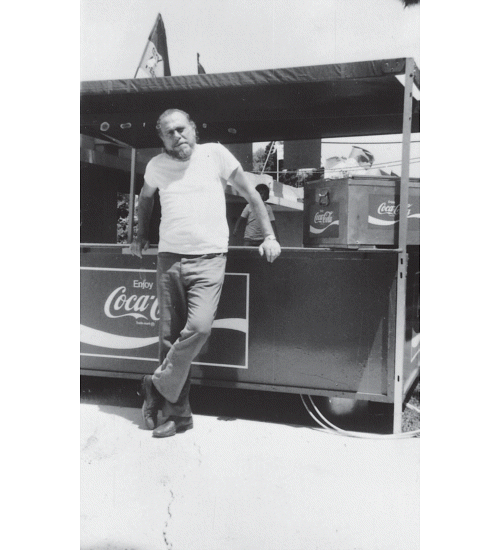

Relaxing in Barnsdall Park, Hollywood, in 1972, aged fi fty-two and free from the post offi ce at last. (

courtesy of Linda King

)

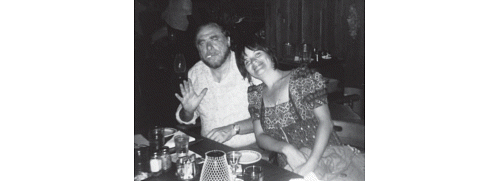

In July, 1972, Bukowski went on a rare vacation to the island of Catalina, just off the coast of California. With him was record company executive Liza Williams whom he was dating after a break-up with Linda King. (

courtesy of Liza Williams

)