Charlottesville Food (13 page)

Read Charlottesville Food Online

Authors: Casey Ireland

The matchbooks at the C&O Restaurant.

Photo by Kevin Haney

.

Too often, the only animals that diners see are the cows dangling from Chick-fil-A billboards or the dancing chickens of Pollos Hermanos on

Breaking Bad

. The industrialization of farming, the accessibility of fast food and the rise of the supermarket have all contributed to an extreme level of disconnect between the consumed and the consumer. While CSAs, farmers' markets and alternative supermarkets allow the health and environmentally conscious to stock their homes with local products, these customers often want that same level of control and understanding when dining outside of the home or farm.

Charlottesville is home to many offerings for diners committed to various levels or conceptions of locavorism, as well as offerings for those for whom a good meal is simply that. A popular catchphrase among Charlottesvillians is how the city has more restaurants per square mile than New York City. While the most recent ReCount survey conducted by the NPD Group situates Charlottesville between Portland and San Francisco as the fourteenth most restaurant-filled per capita city in the United States, the excitement and pride behind the restaurant scene in Charlottesville remains the same.

93

For, after all, what does a city like New York City offer diners that Charlottesville cannot? Accessible late-night options, ethnic hotspots, a variety of cuisines and an even bigger variety of brilliant chefs mark this small city as a culinary powerhouse. Why else would the

New York Times

document ways to spendâand eatâtwenty-four hours in Charlottesville

94

or

Southern Living

write up a tour of chef turned producer Gail Hobbs-Page's home?

95

Charlottesville food has been influenced by the health-conscious simplicity of California cooking, the inquisitive inventiveness of New York and the back-to-our-roots southern charm of Charleston.

Current trends of heritage cooking, seasonal meals, strict regionality and more efficient methods of using ingredients have been well utilized in Charlottesville. It's still easy to find a perfectly cooked rib-eye in the city, but less traditional cuts such as tongue, hanging tenderloin and marrow have been appearing on menus. A proliferation of New Southern restaurants brings the taste of childhood and roadside stops in the Carolinas to the area, with the flavors of pimento cheese and pork belly. Yet despite the in-status of fried chicken and ham hocks, there are plenty of West Coastâinspired stops for a more health-consciousâand waistline-friendlyâmeal. Bowls of delicately scented

pho

, see-through vegetable rolls, light curries and crisp salads are mainstays around town for those looking to eat well and live well. For a town of its size and location in the Virginia countryside, Charlottesville offers diners trends

and

taste.

Though a focus on regionality, seasonality and sustainability has entered the culinary arena, Charlottesville's roots in a more European epicurean tradition still remain a powerful source of inspiration. Veal sweetbreads in a Madeira cream sauce, house-made charcuterie and artisanal cheese plates with selections from France and the United Kingdom abound at many fine-dining restaurants. Foundational sauces borrowed from French

haute cuisine

, Northern Italian pasta dishes and flambéed desserts sit comfortably on the menus of many restaurants still successful after the wave of Alice Watersâinspired cooking. The steak

chinoise

at C&O Restaurant, with its creamy tamari sauce and traditional presentation, is a classic Charlottesville meal alongside a Riverside cheeseburger or a bagel from Bodo's.

One of Charlottesville's greatest culinary successes is its ability to combine the highbrow with the lowbrow, its success with turning local bounty into gourmet excellence. One may pay over $100 for a full meal at Palladio, but the beets in a delicate salad or the filling for plump agnolotti come from farms merely miles away. Perfectly seasoned trout at C&O was pulled out of the streams at Rag Mountain, while both imported San Marzano tomatoes and Rock Barn pork make up a thick ragù at Tavola. The freshest and most unique products at the City Market, farm stand or backyard garden are liquified, sautéed, mashed, grilled or preserved in ways both surprising and comforting.

In recent years, the craze and demand for local food has seemed to have moved from the high to lower classes, whereas the history of self-sustaining food production seems to be the opposite. Gail Hobbs-Page, former chef and current cheesemaker, has found that “southerners grab onto that way of living” in terms of localized, crafted food on account of “olfactory memory and traditions that were handed down or perhaps coming out of poverty.” She muses, “I think we're just coming back to what genetically feels like home,” whether that means backyard tomatoes instead of hothouse hybrids or cooking from-scratch mashed potatoes for the first time.

96

The instance of Sotheby's selling off heirloom vegetables for $1,000 translates onto the dinner table as well, with groups such as Outstanding in the Field offering sit-down dinners on local farms for upward of $200 per person.

The concept of sitting down for a fine meal in the midst of a working farm or cornfield is a study in contrasts. The earthiness and the rusticity of the setting belies the sophistication of the meal, no matter how humble its components. Corn from the field arrives dusted in chipotle pepper powder and liberally sprinkled with Cotija cheese, street food gone gourmet. A herd of cattle heard lowing in the background breaks down into a rather pricey selection of meat options; to put it simplistically, a diner will often pay more for the most simply and naturally raised product. Whether the item is carrots from a certified-organic operation or free-range duck, the challenges of farming and farming sustainably are costs passed on from the farmer to the diner when the farm's product goes to the restaurant.

But perhaps the acts of cooking and assembling ingredients to make a dish and then a meal are inventive processes that deserve a diner's attentionâand their money. Chefs, bakers and food artisans in Charlottesville understand the culinary arts so well, transforming their acts of creation into a form of alchemy. Humble sauvignon blanc grapes, dusted in a smoky gray bloom, become a crisp, pale green wine at Veritas Vineyard. This sauvignon blanc, in turn, gets paired with fresh fish from the Chesapeake Bay, lovely on its own but turned flaky and flavorful with brown butter and almonds. Chefs of Charlottesville understand the power of the understated and the unexpected, whether it be tiny rosemary blossoms scattered on zucchini shavings or a perfectly fried potato. These are chefs taught by southern grandmothers, French chefs at ski resorts or Julia Child on TV. Their methodologies and flavors represent current movements in the restaurant world, but their personalities and stories are uniquely Virginian and particular to Charlottesville.

S

LOW

F

OOD

M

ADE

F

AST

: W

ILL

R

ICHEY

'

S

C

ULINARY

E

MPIRE

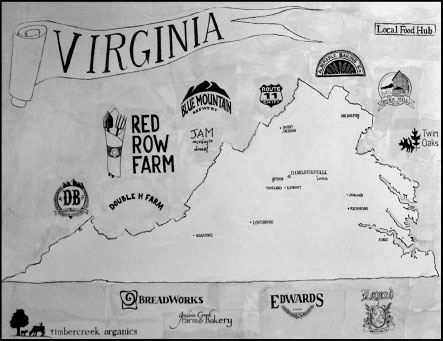

Will Richey, with his homesteader lifestyle and antebellum fashion sense, is one of the most visible and well loved of these culinary characters. Known for his appreciation of both good food and good times, the man who runs Red Row Farm with his family was first known in the area for making really excellent soup. Richey's ownership of Revolutionary Soup and transformation of the punky soup stops into locavore hotspots preceded his founding of the Whiskey Jar, a southern restaurant known for hearty fare and many selections of the eponymous beverage. Richey started off in the area as a UVA student holding wine tastings and then became a cook at L'étoile, a French restaurant with an interest in Virginian history. He purchased Revolutionary Soup, which had only been open three hours a day and run by “punk kids,” in 2005 at his wife's urging. In 2012, Richey directed his interests into running his farm and running the Whiskey Jar with his partners.

A dedication to local food and southern food has informed all of Richey's food endeavors. Though Richey is the third owner of Revolutionary Soup, he's “the first to take it in the local food aspect that it is.”

97

The two restaurants, located downtown and on the Corner near UVA, are examples of slow food done fast. Hearty stews, delicate broths, filling salads and creative sandwiches have inspired “a dedicated local following, and because of that, we get tourists.” Richey has found that most of his customer base is “a core local office group of people who want to eat healthy and want to eat well who believe in local foods.” In comparison, Richey states, “Whiskey Jar is two restaurants in one”: both family-friendly dining and a popular bar. The food at the Whiskey Jar is down-home and surprisingly traditional, with chickory salads and barbecued rabbit served alongside hush puppies and pecan pie. The restaurant gets tourists as well as “regular people who want to learn the whiskeys.” Many customers come in for live music, though to Richey, the most interesting people are the people coming in for the food.

Steve Zissou and a collection of spirits along the brick walls of the Whiskey Jar's bar.

Photo by Kevin Haney

.

Richey was raised eating good food and always liked to go to restaurants, even starting tasting groups in college. Working at a wine shop was his first foray into a career as a gourmand before getting a job at L'étoile; according to Richey, working at that restaurant “was the life-changer.” Richey was interested in gourmet food before local food; his interests began with the “French thing and fancy food. Food at its finest.” Richey tells how Mark Reskey, owner of L'étoile, was a big Virginia history buff, interested in culinary questions like, “How can we re-create what the colonialists were eating?” Reskey did research at Monticello and created meals based on that. “It was definitely home,” Richey admits.

The questions of “Who am I?” and what home tastes like underlie much of Richey's culinary philosophy. “My family's from the South,” he states. “We're Virginians.” With a laugh, Richey tells happy stories of “cooking with old ladies.” While he may have “learned professional cooking from friends,” Richey attests that his best recipes are his mother's. “I prefer the food eaten by my people,” Richey admits, despite being a self-confessed Francophile with a love of fine wines and gourmet offerings. “I wanted it to be a lifestyle, tracking heirloom varieties. How did we lose that?” Richey muses. “We've lost that in all aspects of the cultureânow it's homogenized and generic.”

The ingredients and offerings at both Revolutionary Soup locations and at the Whiskey Jar, as well as the ways in which Richey sources his materials, are anything but basic. The percentage of local ingredients he uses at all three restaurants falls down to 50 percent in winter though tops at 80 percent in summer. They purchase local meats all year long; all the proteins at Whiskey Jar are local, and almost all at Revolutionary Soup are local. Richey is influenced by Anson Mills, a Charleston company that is also a big supporter of Southern Foodways Alliance. Richey and his cooks try to preserve a lot of summer produce, at times filling freezers with the last of summer's tomato pulps. Richey's goal for the future of his restaurants is increased organization, turning the Corner kitchen into a canning location.

When Richey's restaurants can't get local, they at least try to get organic. “I don't want to overstate what we do because then it belittles the good things we do,” he attests. “Local dairy would kill you price-wise; we go through so much butter. At home, it's buy the good stuff, eat less of it, save other places.” Part of Richey's ability to keep overhead down is his use of large-scale food distribution companies to his advantage. Richey has “made a lot of ground with Sysco” due to a rep who allows Richey to pursue his locavore interests, telling him, “I can source certain local things for you,” like Byrd Mill, Edward's Ham products and Virginia peanuts. Both a self-confessed “Gen-X anti-establishmentarian” and an optimist, Richey has faith that one can get big institutions to work for the community, not vice versa.