Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion (30 page)

Read Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion Online

Authors: George M. Taber

BOOK: Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion

9.93Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

They arrived at Scapa Flow in Scotland on May 27 and then traveled down the western coast of Britain, arriving at Plymouth on May 29 at 5:00 in the morning. A representative from the Bank of England met the ship and had the 547 cases, 302 large and 245 small ones, transferred to a train that had a military guard. Haslund again demanded and received a receipt for the gold from the Bank of England official.

44

44

On June 1, Sir Cecil Dormer, the British Minister to Oslo, flew to Tromsø and informed the Norwegian government that all Allied forces were being withdrawn from their country in order to strengthen units fighting further south. Germany had invaded Holland, Belgium, and France on May 10, and the war there was going badly. The Norwegian government held its last meeting on native soil on June 7. That afternoon the cabinet, king, and crown prince boarded the British cruiser

Devonshire

in a light summer rain and set out for Gourrock near Glasgow. They arrived in Scotland the morning of June 10 and traveled by train to London. Britain’s King George met his royal counterpart at the railroad station and took the two by car to Buckingham Palace, where they stayed for a few days before beginning nearly four years in exile. The king sent back a radio broadcast to his country explaining that he had left and pleaded: “All we ask of you is: Hold out in loyalty to our dear fatherland!”

45

Devonshire

in a light summer rain and set out for Gourrock near Glasgow. They arrived in Scotland the morning of June 10 and traveled by train to London. Britain’s King George met his royal counterpart at the railroad station and took the two by car to Buckingham Palace, where they stayed for a few days before beginning nearly four years in exile. The king sent back a radio broadcast to his country explaining that he had left and pleaded: “All we ask of you is: Hold out in loyalty to our dear fatherland!”

45

The Norwegian cabinet soon decided that it had become too dangerous to keep the nation’s gold in London. France was on the brink of falling to the Nazis, and it was believed that Britain would be the next target. Hitler had already given General Keitel orders to plan for

Unternehmen Seelöwe

(Operation Sea Lion), the cross-Channel invasion.

Unternehmen Seelöwe

(Operation Sea Lion), the cross-Channel invasion.

Despite the serious danger from German U-boat attacks in the North Atlantic during the summer of 1940, the Norwegian government voted to ship the country’s gold to Canada and the U.S. Canada, as a member of the British Commonwealth, was already in the war, but the United States was still a neutral. The cabinet decided, though, to keep in London one ton of gold, worth approximately $1 million, to pay for the costs of the government-in-exile, the king, and his family.

Major Arne Sunde, who had directed the escape of gold from Åndalsnes on the

Galatea

, was now in London and became part of a taskforce for the shipment across the Atlantic. He decided that the Norwegian merchant ship

Bomma

, a 1,450-ton freighter, would first make a test run to see if it could safely arrive in North America. The vessel had been built in 1938, and its captain Louis Johannesen had been at sea since he was a teenager during the age of sail. Johannesen and his ship had recently escaped from Molde under the nose of the Germans.

46

Galatea

, was now in London and became part of a taskforce for the shipment across the Atlantic. He decided that the Norwegian merchant ship

Bomma

, a 1,450-ton freighter, would first make a test run to see if it could safely arrive in North America. The vessel had been built in 1938, and its captain Louis Johannesen had been at sea since he was a teenager during the age of sail. Johannesen and his ship had recently escaped from Molde under the nose of the Germans.

46

The

Bomma

was repainted a dull gray, and its name was removed to make it look like a non-descript cargo ship. In early June, the vessel left Falmouth on Britain’s south coast to begin the trip across the Atlantic. Two Norwegians who had been with the gold during most of its odyssey, Ole Colbjørnsen from the Bank of Norway and Fredrik Haslund, were assigned to make the first trip. Haslund was unhappy with the new assignment because he wanted to return to Norway and continue the fight. The plan was to deliver part of the gold to the Bank of Canada in Montreal and part to the U.S. Federal Reserve in Washington, D.C. Lloyd’s of London insured the gold against loss at sea for $52,000 per million dollars of value.

Bomma

was repainted a dull gray, and its name was removed to make it look like a non-descript cargo ship. In early June, the vessel left Falmouth on Britain’s south coast to begin the trip across the Atlantic. Two Norwegians who had been with the gold during most of its odyssey, Ole Colbjørnsen from the Bank of Norway and Fredrik Haslund, were assigned to make the first trip. Haslund was unhappy with the new assignment because he wanted to return to Norway and continue the fight. The plan was to deliver part of the gold to the Bank of Canada in Montreal and part to the U.S. Federal Reserve in Washington, D.C. Lloyd’s of London insured the gold against loss at sea for $52,000 per million dollars of value.

Colbjørnsen and Haslund traveled to Falmouth on June 10, and inspected the cargo. The cases had been repacked in London, and the numbers were registered on a new manifest. Ten tons of gold was packed into 120 small boxes and 130 larger ones. They were then put on a towboat and carried out to the

Bomma

, which was anchored in the outer harbor. Colbjørnsen, Haslund, and Captain Johannesen watched over the cargo until it was safely in the hold under lock and key.

47

Bomma

, which was anchored in the outer harbor. Colbjørnsen, Haslund, and Captain Johannesen watched over the cargo until it was safely in the hold under lock and key.

47

The

Bomma

left Falmouth at 2:00 in the morning on June 15. Three hours and forty minutes later, it joined a convoy near Lizard Point, the southern-most spot in Britain. The formation consisted of thirteen vessels, mostly armed. One small destroyer served as escort. The

Bomma

was unarmed, but had anti-magnetic equipment to protect it against mines. After setting out, the convoy poked along on a zigzag course at eight knots to lessen the danger of being attacked.

Bomma

left Falmouth at 2:00 in the morning on June 15. Three hours and forty minutes later, it joined a convoy near Lizard Point, the southern-most spot in Britain. The formation consisted of thirteen vessels, mostly armed. One small destroyer served as escort. The

Bomma

was unarmed, but had anti-magnetic equipment to protect it against mines. After setting out, the convoy poked along on a zigzag course at eight knots to lessen the danger of being attacked.

The weather on the crossing was good, and the trip smooth. After nine days at sea, the convoy was broken up, with each ship going its own way. The

Bomma

increased its speed to thirteen knots and headed toward the Gulf of St. Lawrence with plans to make a first stop in Montreal. Soon, however, heavy fog rolled in, and the temperature fell rapidly. Colbjørnsen was fearful of hitting an iceberg and ordered the captain to change the course to due south. The captain suggested landing in either Boston or New York City, but the banker overruled him in favor of Baltimore. He thought that the arrival of the gold would be less conspicuous there, and he also wanted to be near the Federal Reserve’s headquarters.

Bomma

increased its speed to thirteen knots and headed toward the Gulf of St. Lawrence with plans to make a first stop in Montreal. Soon, however, heavy fog rolled in, and the temperature fell rapidly. Colbjørnsen was fearful of hitting an iceberg and ordered the captain to change the course to due south. The captain suggested landing in either Boston or New York City, but the banker overruled him in favor of Baltimore. He thought that the arrival of the gold would be less conspicuous there, and he also wanted to be near the Federal Reserve’s headquarters.

While the

Bomma

was still in the Atlantic, Wilhelm Morgenstierne, the Norwegian Minister in Washington, hastened to set up a gold account with the Federal Reserve in New York so that the cargo could be deposited upon arrival. He had been in frequent contact with American officials in both Washington and New York for several days about the imminent arrived of the valuable cargo. On June 24, the minister sent a special delivery letter to L. Werner Knoke, a vice president of the Federal Reserve, asking to open a gold account in the name of the Royal Norwegian Government. He explained that he had the power of attorney to “operate all accounts and other assets in the United States belonging to the Norwegian Government.”

48

Bomma

was still in the Atlantic, Wilhelm Morgenstierne, the Norwegian Minister in Washington, hastened to set up a gold account with the Federal Reserve in New York so that the cargo could be deposited upon arrival. He had been in frequent contact with American officials in both Washington and New York for several days about the imminent arrived of the valuable cargo. On June 24, the minister sent a special delivery letter to L. Werner Knoke, a vice president of the Federal Reserve, asking to open a gold account in the name of the Royal Norwegian Government. He explained that he had the power of attorney to “operate all accounts and other assets in the United States belonging to the Norwegian Government.”

48

When the

Bomma

arrived in Baltimore at 5:30 A.M. on June 28, Captain Johannesen and his crew ran into problems because the Norwegians didn’t have any document giving them permission to import gold. So the captain declared that the ship had no cargo on board and only had ballast for stability. Armed U.S. Customs officials boarded the

Bomma

and forbid everyone except the captain from leaving the ship.

49

Bomma

arrived in Baltimore at 5:30 A.M. on June 28, Captain Johannesen and his crew ran into problems because the Norwegians didn’t have any document giving them permission to import gold. So the captain declared that the ship had no cargo on board and only had ballast for stability. Armed U.S. Customs officials boarded the

Bomma

and forbid everyone except the captain from leaving the ship.

49

With the help of Morgenstierne, Colbjørnsen and Haslund were finally allowed to travel to Washington. Not knowing what to expect in the U.S., they took with them two bags that each contained one thousand twenty-kroner gold coins. They figured that would cover any expenses, but left them temporarily at the Federal Reserve’s Baltimore office. Once in Washington, they arranged to ship 130 cases of gold to the Federal Reserve Bank in New York and 120 cases to the Bank of Canada in Montreal. The Federal Reserve board finally approved the Norwegian gold account the same day the bullion arrived.

The evening of July 1, the

Bomma

moved to Canton Pier 3 and with a small army of police and customs agents standing guard, the ship’s crew moved the gold into three armored trucks. Captain Johannesen wrote in his log that the disembarkation was finished at 10:00 P.M. The gold went to the Camden railroad station, where a special one-car train carried it to New York City. The rest of the shipment left by train for Canada. That same day, Minister Morgenstierne sent the Federal Reserve’s Knocke a letter asking that the gold from the

Bomma

be put in the Norwegian account. The minister gave the value of the gold as “approximately” $6 million. Following an agreement with the Federal Reserve, Colbjørnsen stayed in the U.S., while Haslund traveled to Montreal to meet with Norwegian and Canadian officials about the gold that would be arriving there.

50

Following that first successful trip, a Norwegian armada began bringing gold to North America. Later shipments were limited to a maximum of six tons. By the end of July 1940, eleven Norwegian ships had successfully carried the entire Norwegian gold horde, with the exception of the ton kept in London, across the North Atlantic. Thirty-four tons went to the Bank of Canada and were stored in Ottawa, while 14.7 tons eventually went to the New York Federal Reserve Bank.

51

Bomma

moved to Canton Pier 3 and with a small army of police and customs agents standing guard, the ship’s crew moved the gold into three armored trucks. Captain Johannesen wrote in his log that the disembarkation was finished at 10:00 P.M. The gold went to the Camden railroad station, where a special one-car train carried it to New York City. The rest of the shipment left by train for Canada. That same day, Minister Morgenstierne sent the Federal Reserve’s Knocke a letter asking that the gold from the

Bomma

be put in the Norwegian account. The minister gave the value of the gold as “approximately” $6 million. Following an agreement with the Federal Reserve, Colbjørnsen stayed in the U.S., while Haslund traveled to Montreal to meet with Norwegian and Canadian officials about the gold that would be arriving there.

50

Following that first successful trip, a Norwegian armada began bringing gold to North America. Later shipments were limited to a maximum of six tons. By the end of July 1940, eleven Norwegian ships had successfully carried the entire Norwegian gold horde, with the exception of the ton kept in London, across the North Atlantic. Thirty-four tons went to the Bank of Canada and were stored in Ottawa, while 14.7 tons eventually went to the New York Federal Reserve Bank.

51

Only one stray bag of Norwegian gold was lost in the whole transport, when a box was damaged aboard the

HMS Glasgow

on its way to Britain. A sailor on board stole a bag of Hungarian gold coins from the box. He then went on a drinking spree on the Glasgow waterfront, paying for drinks with his new wealth. He was quickly arrested, and given ninety days of detention. The remaining coins were sent to the Norwegian account at the Bank of England.

52

HMS Glasgow

on its way to Britain. A sailor on board stole a bag of Hungarian gold coins from the box. He then went on a drinking spree on the Glasgow waterfront, paying for drinks with his new wealth. He was quickly arrested, and given ninety days of detention. The remaining coins were sent to the Norwegian account at the Bank of England.

52

While still in Washington in early August 1940, Fredrik Haslund wrote an official report on the rescue of the Norwegian gold. At the end of it, he modestly stated that his success “would not have been possible without the energy and the devotion to duty of many persons.” He suggested that after the war everyone who helped him should be awarded a gold 20 kroner coin with a picture of the Norwegian king on one side and a “suitable inscription” on the other. No rewards, though, were ever given out to the courageous men who saved Norway’s gold.

53

53

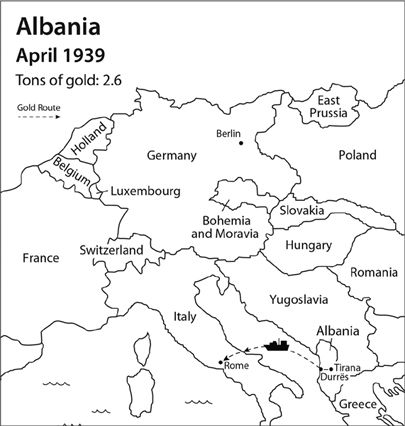

Chapter Fourteen

ITALY CRUSHES ALBANIA

Albania has spent most of its history being kicked around by its bigger neighbors. Greece, Rome, and the Byzantine Empire at various times ruled the poor, rugged land torn between the western and eastern cultures. Ismail Qemali, a veteran leader of the Albanian nationalist movement, declared his country’s independence on November 28, 1912, and he became its first head of state. The London Peace Conference of 1912-1913 recognized it as an independent country, but then World War I turned the Balkans into a bloody battlefield. After the war, the Versailles Conference initially split up Albania’s territory among Greece, Italy, and Yugoslavia. Woodrow Wilson in the name of national self-determination, however, torpedoed that plan.

In its early years, Albania endured a series of unstable governments. Ahmed Bey Zogu, the son of a prominent landowner, became the country’s first president in January 1925 and turned it into a police state. On September 1, 1928, the Albanian parliament declared the country a kingdom, and Zogu named himself King Zog of the Albanians. He aligned his nation with Mussolini as a way to protect it from other neighbors. Italy is only forty miles east across the Adriatic Sea.

1

1

Albania remained a poor country with virtually no industry that survived mostly on peasant farming. It was anxious, though, to get on the fast track to the modern world. Italy became an important partner in its financial development. Albania also tried to have close relations with Britain because of its financial center and as a counterbalance to Italy. Neville Chamberlain called Albania a Baltic Belgium, meaning that it was a small country that had to be protected from powerful neighbors. Zog was aware of the danger of getting too close to Mussolini, and once told the British minister, “Never will I fall into the hands of Italy.”

2

2

For a young country with an undeveloped economy and little financial experience, Albania had a surprisingly sophisticated central bank. The National Bank of Albania (

Banka e Shqipërisë

) was established in the summer of 1925 with capital of 12.5 million gold francs. Italian financiers put up three-quarters of the start-up money, which gave them the dominant role in the country’s economy. The other investors were Yugoslav, Swiss, and Belgian banks.

3

Banka e Shqipërisë

) was established in the summer of 1925 with capital of 12.5 million gold francs. Italian financiers put up three-quarters of the start-up money, which gave them the dominant role in the country’s economy. The other investors were Yugoslav, Swiss, and Belgian banks.

3

Not surprisingly since foreign bankers ran the financial institutions, the Albanian government and its central bank were very conservative. They kept a tight hand on the economy, and inflation was almost nonexistent. The nation’s founders believed strongly in gold. The currency was the lek, and the monetary system was based on the Albanian gold franc. The central bank issued gold coins in denominations of 10, 20, and 100 francs in addition to silver and nickel pieces in smaller denominations. Paper money was backed by forty percent gold. The bank’s bullion holdings increased from 1.9 million gold francs in 1927 to 9.2 million in 1938.

4

Looking back at that era, the International Currency Review of 1977 wrote, “Before the Second World War, the Albanian franc was one of the strongest currencies in Europe. The notes of the Albanian National Bank issued from March 1926 onwards were, in effect, bullion certificates.”

5

4

Looking back at that era, the International Currency Review of 1977 wrote, “Before the Second World War, the Albanian franc was one of the strongest currencies in Europe. The notes of the Albanian National Bank issued from March 1926 onwards were, in effect, bullion certificates.”

5

Once the central bank was established, the government worked hard to build up the gold holdings even more by having private citizens turn in their jewelry and other gold pieces in exchange for the country’s new paper currency. That private gold was then put into the central bank reserves. Whenever possible, the bank also bought more gold in London.

Albania had the unfortunate experience to be in the middle of European politics between the wars. Mussolini was both nearby and on the march. His early success in conquering Ethiopia in 1935 had turned him into a new international figure, but Hitler’s rapid rise to power around the same time eclipsed Il Duce. Mussolini viewed his Fascist rival with admiration, envy, and suspicion. German intentions in the Balkans, which he considered to be his own sphere of influence, also worried him. By 1938, Albania looked like a close and an easy target for Rome and a way for Italy to reestablish its leadership of Europe’s fascist movement.

Other books

Spy Games: Lethal Limits by Downing, Mia

Legally Undead by Margo Bond Collins

Blue Ribbon Summer by Catherine Hapka

Sister of Silence by Daleen Berry

Last Train to Paris by Michele Zackheim

Wondrous Strange by Lesley Livingston

On Being Wicked by St. Clare, Tielle

Wired by Liz Maverick

Lincoln: A Life of Purpose and Power by Richard J. Carwardine

Wink of an Eye by Lynn Chandler Willis