Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (42 page)

Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

11.23Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

UN officials at Headquarters were bitterly divided over the war, and many looked to Vieira de Mello, the under-secretary-general for humanitarian affairs, for guidance. But either because he was conflicted or because he did not want to alienate those he did not agree with, he did not give it. He never openly declared whether on balance he opposed or supported the NATO war. “Even with a small group of us over drinks he would make his views appear totally neutral,” recalls Rashid Khalikov, a Russian colleague in OCHA.

Vieira de Mello knew one thing: His personal view of NATO’s war was irrelevant. To the degree that citizens of the world looked to the UN for comment, they looked to Secretary-General Annan, who had a checkered past when it came to responding to crimes against humanity and genocide. He had been in charge of the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations during the Rwandan genocide and the Srebrenica massacre, and he had been justly criticized for failing to sound the alarm. Annan felt that the very countries that had turned their backs on the Rwandans and the Bosnians were the ones making him their scapegoat, but he knew that his name would appear in the history books beside the two defining genocidal crimes of the second half of the twentieth century. Since becoming secretary-general in 1997, he had used his pulpit to publicly urge governments to embrace a new “norm of humanitarian intervention” to halt atrocities.

Nonetheless Annan was the primary guardian of the UN rulebook. Since NATO was acting in defiance of that rulebook, the war’s critics expected him to decry NATO’s military action. But in this, the Security Council’s first major crisis on his watch, Annan had two competing fears: Either the United States would come away believing it could do as it chose, or the Russians would be so disgusted with the UN’s failure to deter the United States that it would turn away from the institution.The first day of the war Annan thus issued a statement in which he tried to have it both ways. He lamented the use of force but added the following jarring sentence:“It is indeed tragic that diplomacy has failed, but

there are times when the use of force may be legitimate in the pursuit of peace

.”

31

there are times when the use of force may be legitimate in the pursuit of peace

.”

31

To the delight of the Clinton administration, the

New York Times

headline the day after the launch of the war read “THE SECRETARY-GENERAL OFFERS IMPLICIT ENDORSEMENT OF RAIDS.”

32

Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s ambassador to the UN, stormed into Annan’s office and denounced him for his complicity in the illegal NATO attack. Vieira de Mello too told Hochschild that Annan had gone too far to appease the United States.

New York Times

headline the day after the launch of the war read “THE SECRETARY-GENERAL OFFERS IMPLICIT ENDORSEMENT OF RAIDS.”

32

Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s ambassador to the UN, stormed into Annan’s office and denounced him for his complicity in the illegal NATO attack. Vieira de Mello too told Hochschild that Annan had gone too far to appease the United States.

As the war progressed, Annan continued to walk a fine line between making clear that the NATO war technically violated the Charter and stressing that atrocities demanded a response. “Unless the Security Council is restored to its preeminent position as the sole source of legitimacy on the use of force, we are on a dangerous path to anarchy,” the secretary-general said in one speech. “But equally importantly, unless the Security Council can unite around the aim of confronting massive human rights violations and crimes against humanity on the scale of Kosovo, then we will betray the very ideals that inspired the founding of the United Nations.” He continued, “The choice must not be between Council unity and inaction in the face of genocide, as in the case of Rwanda, on the one hand; or Council division, and regional action, as in the case of Kosovo, on the other.”

33

33

Annan kept speaking out, both denouncing the horrors and asserting the indispensability of the UN. On April 7, two weeks into NATO’s war, he delivered a speech at the UN Commission on Human Rights in Geneva in which he said:

When civilians are attacked and massacred because of their ethnicity, as in Kosovo, the world looks to the United Nations to speak up for them. When men, women and children are assaulted and their limbs hacked off, as in Sierra Leone, here again the world looks to the United Nations.When women and girls are denied their right to equality, as in Afghanistan, the world looks to the United Nations to take a stand. . . . We will not, and we cannot accept a situation where people are brutalized behind national boundaries.

Annan closed with a line that Vieira de Mello triple-underlined on his copy of the speech:

For at the end of the twentieth century, one thing is clear: A United Nations that will not stand up for human rights is a United Nations that cannot stand up for itself.

34

34

After a few days of NATO bombing, pundits shifted away from debating whether the war was legal to discussing whether its ghastly consequences could be contained. In September 1995, when NATO had finally intervened forcefully in Bosnia, it brought the Bosnian Serbs to heel with remarkable speed.This precedent, as well as NATO’s colossal 300-1 superiority in military expenditures, had left U.S. and U.K. planners bullish about the odds of a swift air campaign in Kosovo.

35

On the first day of the war, President Clinton had said that the United States had no intention of deploying ground troops. He expected the Serbs to surrender after just a few days.

35

On the first day of the war, President Clinton had said that the United States had no intention of deploying ground troops. He expected the Serbs to surrender after just a few days.

But Milošević had other ideas. Within hours of NATO’s first attack on March 24, he launched Operation Horseshoe, using prepositioned Serbian police and paramilitary forces to systematically empty Kosovo of ethnic Albanians. Masked gunmen in uniforms turned up in villages and threatened to kill any individual who refused to leave. By March 29, some 4,000 ethnic Albanians were pouring out of Kosovo per hour. In the first week more than 100,000 Kosovars streamed into Albania and 28,000 entered Macedonia, while another 35,000 fled to Montenegro. And in the days ahead they kept coming, by foot, by car, by train, and on tractors.

UNHCR had expected a maximum of 100,000 refugees to spill into neighboring countries, so they were overwhelmed when ten times that number crossed.

36

Sadako Ogata rushed staff to the border who hurried to fly in extra food stocks, set up tents, and negotiate with neighboring Macedonia, which tried to deny entry to the refugees. But in the early days, when the petrified Kosovars crossed the border into Macedonia and Albania, they found almost nobody to welcome them. Indeed, in Macedonia five times more international journalists awaited the refugees than UNHCR staff.

37

36

Sadako Ogata rushed staff to the border who hurried to fly in extra food stocks, set up tents, and negotiate with neighboring Macedonia, which tried to deny entry to the refugees. But in the early days, when the petrified Kosovars crossed the border into Macedonia and Albania, they found almost nobody to welcome them. Indeed, in Macedonia five times more international journalists awaited the refugees than UNHCR staff.

37

Based in New York, Vieira de Mello could do little to help the refugees, beyond hoping that his former colleagues at UNHCR caught up with the flow. Telegenic and articulate, he took to the airwaves to shift attention from the UN’s lack of preparation to the ongoing suffering of Kosovar Albanians. “Reports of masked men in uniforms knocking on doors and telling people to leave or be killed are countless,” Vieira de Mello told reporters. “We are witnessing the emptying of ethnic Albanians from Kosovo.”

38

Most of the refugees reaching Macedonia and Albania were women, children, and the elderly, he said, which raised “the disturbing question as to the fate of a large proportion of Kosovar Albanian males within Kosovo.”

39

No international aid workers were present inside Kosovo, and less than four years after the massacre in Srebrenica, he feared that the absence of men could well mean the massacre of men.

38

Most of the refugees reaching Macedonia and Albania were women, children, and the elderly, he said, which raised “the disturbing question as to the fate of a large proportion of Kosovar Albanian males within Kosovo.”

39

No international aid workers were present inside Kosovo, and less than four years after the massacre in Srebrenica, he feared that the absence of men could well mean the massacre of men.

Although UNHCR’s reputation was severely bruised by the early chaos, its fieldworkers quickly got their footing, amassing enough food and tempo-rary

shelter to defuse the emergency. Families in Albania displayed remarkable generosity toward their Kosovar kin, and very few refugees died of disease, exposure, or starvation. The emergency abated. Some 800,000 Kosovar Albanians settled into refugee camps.

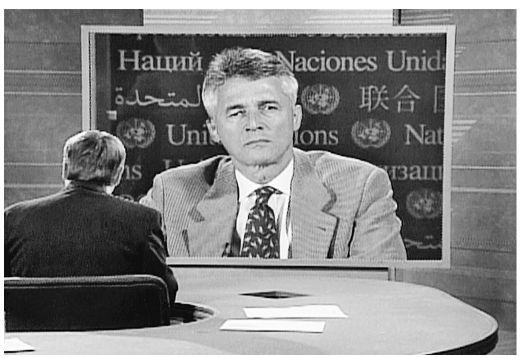

The

MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour,

April 28, 1999.

MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour,

April 28, 1999.

Initially, they had reason to fear their exile would be permanent. Clinton’s renunciation of ground troops had convinced Milošević that, although his forces were hopelessly outgunned, they could wait out the air attacks until domestic public opinion in NATO countries turned against the war. Events on the battlefield augured well for the Serbs. Serb antiaircraft gunners shot down a U.S. F-117 stealth bomber on March 28. Four days later Serb forces captured three U.S. soldiers near the Macedonia-Yugoslav border. On April 12, NATO struck a passenger train south of Belgrade, killing thirty civilians and forcing Clinton to issue a public apology. Two days later NATO hit a convoy of families in flight, leaving sixty-four dead. On April 23, NATO destroyed the Serbian state television building, killing ten.

The heads of state of the nineteen NATO countries had expected to gather in triumph on April 23-25 in Washington to celebrate NATO’s fiftieth birthday. But the alliance’s first-ever war cast a pall on the occasion. And the bad news kept coming. On May 2 a U.S. F-16 fighter jet crashed inside Serbia (though its pilot was rescued). Three days later NATO suffered its first fatalities, as two U.S. Army pilots on a training mission in Albania died when their Apache helicopter crashed. On May 7 a NATO cluster bomb aimed at a military airport in Niš went astray and hit a hospital and a fruit and vegetable market, killing fifteen Serbs and wounding seventy.

NATO’s lowest point came at 9:46 p.m. on May 7. Relying on an out-of-date map, American pilots fired three cruise missiles at what they thought was a Serbian government building but that proved to be the Chinese embassy. As firemen descended on the scene, a blood-soaked, frantic Chinese cultural affairs adviser appeared on Serbian television, saying, “We haven’t found some of my colleagues.” More than twenty people in the embassy were wounded, and three were killed. Chinese ambassador Pan Zhanlien stood before the ruins and said, “The People’s Republic has been attacked.” In Beijing a mob gathered at the U.S. embassy, trapping the ambassador inside. Protesters in the NATO countries of Greece, Italy, and Germany decried the civilian toll of the war.

40

A spokesman for Annan said the secretary-general was “shocked and distressed” at the growing number of deadly NATO mistakes.

41

40

A spokesman for Annan said the secretary-general was “shocked and distressed” at the growing number of deadly NATO mistakes.

41

NATO’s struggles on the battlefield caused the UN’s star to shine brighter.The Western allies started to recognize that, while they had the military prowess to inflict severe harm, they would not necessarily succeed in extracting a surrender from Belgrade. For that they would need Serbia’s historic backer, Russia, to press for peace. The Russians, who were not quick to forgive NATO for launching the war, attached a condition to their cooperation: The UN (where Moscow had great clout) rather than NATO (from which Moscow was excluded) would play the dominant role in any postwar transition.

Vieira de Mello had his own ideas about how to make the UN relevant again, and they did not entail waiting for the Russians to broker a deal. In a senior staff meeting in early May, as Annan described the criticisms he was getting for not condemning NATO, Vieira de Mello spoke up: “Well, there’s one area we can take a stand,” he said, “the humanitarian area.” “Yes,” said Annan,“but what can we do that we are not already doing?” Vieira de Mello answered, “We can get inside Kosovo.”

It was a stroke of political genius. He would lead the first international team into Kosovo since NATO bombing had begun forty days before. The UN would place unarmed officials behind the front lines in a province from which Kosovars were fleeing and that NATO ground forces were avoiding. By entering Kosovo, Vieira de Mello thought he could ascertain the fate of the displaced civilians who had not made their way to safety and assess the extent of NATO’s collateral damage. The trip would instantly elevate the UN’s profile and might even do some good. Annan leaped at the idea, proposing it to the Security Council the following day.

The Russians were elated. Believing Vieira de Mello’s mission would aid his Serbian allies, Ambassador Sergei Lavrov told Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott,“It is no accident that Sergio and I have the same name!” Lavrov urged Vieira de Mello to document the severe economic and environmental devastation caused by NATO. U.S. and U.K. officials had the opposite reaction. With new reports of NATO collateral damage surfacing each day, and with no sure victory in sight, NATO planners did not want to have to go out of their way to avoid hitting UN personnel and thus reduce their already-thin list of targets. Because Yugoslav officials on the ground would block the UN’s movement, the allies were also concerned that Vieira de Mello would emerge with more horror stories about stray NATO missiles than about Serb brutality. Nancy Soderberg, the acting U.S. ambassador to the UN, called him on May 5 to complain about the mission. “Sergio, this is a stupid idea,” she said. “You are playing right into Serb hands.” Firmly but gently he pushed back. “Nancy, my dear, I’m afraid this is nonnegotiable,” he said. “We are the United Nations, and no country, not even one as powerful as yours, can tell us where we can and cannot go.” U.S. officials nixed a planned Council statement welcoming the initiative.

42

The following day the divided Council instead issued a noncommittal statement saying it “took note” of the mission “with interest.”

43

42

The following day the divided Council instead issued a noncommittal statement saying it “took note” of the mission “with interest.”

43

Other books

Murder in the Choir (The Jazz Phillips Mystery Series) by Joel B Reed

The Telling by Ursula K. Le Guin

The Cat Who Played Post Office by Lilian Jackson Braun

Single Ladies by Blake Karrington

Mariette in Ecstasy by Ron Hansen

Sanctuary (Family Justice Book 3) by Halliday, Suzanne

Torn Asunder by Ann Cristy

Kati Marton by Hidden Power: Presidential Marriages That Shaped Our History

Face to Face (The Deverell Series Book 2) by Susan Ward

Someday Find Me by Nicci Cloke