Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (7 page)

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

10.81Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

He and Annie lived in an apartment near her parents’ home in the French town of Thonon. After a few years they built a permanent home for themselves in the French village of Massongy, a twenty-minute drive from Thonon and a half hour from his workplace in Geneva. In 1975 the couple moved to Mozambique, where he joined a UNHCR staff that was caring for the 26,000 refugees who had fled white supremacist rule and civil war in neighboring Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). He had been named the deputy head of the office, but owing to an absent boss he ended up effectively running the mission, an enormous responsibility for one just twenty-eight years old. Initially the novelty of new tasks and a new region sustained him. He particularly enjoyed getting to know independence fighters and leaders from Rhodesia, South Africa, and East Timor, the tiny former Portuguese colony that had just been brutally annexed by Indonesia.Yet after a year in the job he began mailing long, restless letters to his senior UN colleagues in Geneva, inquiring about other job postings. It was as if, as soon as he settled into a routine by helping develop systems to house and feed the refugees, he was eager to move on. When word of these ambitions began circulating around UNHCR headquarters, Franz-Josef Homann-Herimberg, an Austrian UN official whom Vieira de Mello had often approached for career advice, warned him, “Sergio, you’ve got to cool it. It is natural that you don’t want to wait until jobs are offered to you, but you are starting to get a reputation for being one who spends his time plotting his next move.”

In 1978 Vieira de Mello and Annie returned to France, where she gave birth to a son, Laurent. Then they moved to Peru, where Vieira de Mello became UNHCR’s regional representative for northern South America and attempted to help asylum-seekers who were fleeing the Latin American military dictatorships. This assignment moved him closer to home, allowing him to spend more time in Brazil than he had in the previous decade. In 1980 he and Annie had a second son, Adrien.

Vieira de Mello kept a permanent stash of Johnnie Walker Black Label— an upgrade from Jamieson’s Red Label—in his desk drawer at his UNHCR office or in his suitcase while on the road. He also kept a framed photograph of his mentor on his desk at UNHCR. He took it with him on most field assignments and sometimes placed it on hotel nightstands during short overseas trips. A decade or so after Jamieson’s death, Vieira de Mello called Maria Therese Emery, Jamieson’s longtime secretary, and apologetically asked if she might be able to give him another photograph of Jamieson. “I’ve been in too many hot places,” he said. “The photo I have has faded in the sun.”

Two

“I WILL NEVER USE THE WORD ’UNACCEPTABLE’ AGAIN”

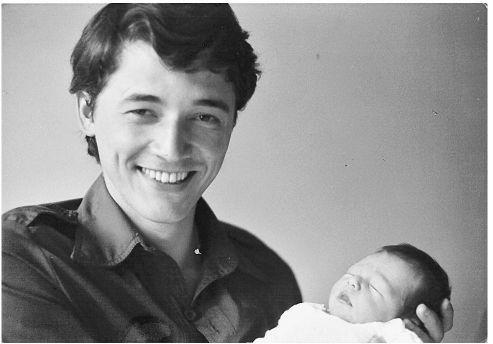

Vieira de Mello holding his six-day-old son Laurent, June 8, 1978.

It was in Lebanon that Vieira de Mello first encountered terrorism. Although he knew that many promising careers were torpedoed in the Middle East, for him the region’s most damning qualities—its contested geography, political turmoil, and religious extremism—were what enticed him. By 1981 he had been performing purely humanitarian tasks at UNHCR for twelve years, and he felt his learning curve had leveled off. When he heard from a colleague that a UN job had opened up in Lebanon, which he judged the most challenging of all UN assignments, he submitted his résumé and was selected to become political adviser to the commander of peacekeeping forces in the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL). Just thirty-three years old, he took leave of UNHCR, his home agency, with strong convictions about the indispensability of the UN’s role as an “honest broker” in conflict areas. But over the next eighteen months he would see for the first time how little the UN flag could mean to those consumed with their own grievances and fears. Lebanon was the place whereVieira de Mello’s youthful absolutism began to give way to the pragmatism for which he would later be known.

In 1978, after a Palestinian terrorist attack on the road north of Tel Aviv left thirty-six Israelis dead, some 25,000 Israeli forces had invaded southern Lebanon. Israeli leaders said the invasion was aimed at eradicating strongholds of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which was staging ever-deadlier cross-border attacks from southern Lebanon into northern Israel with the aim of forcing Israelis to end the occupation of Palestinian territories in the West Bank and Gaza. In its weeklong offensive, Israel captured a fifteen-mile-deep belt of Lebanese territory.

1

1

Only the large coastal city of Tyre, and a two-by-eight-mile sliver of territory north of the Litani River, had remained in Palestinian hands. Although the United States and the Soviet Union then agreed on little at the UN Security Council, they did agree that Israeli forces should withdraw from Lebanon and that UN peacekeepers should be sent to monitor their exit.

3

2

In an editorial that reflected what would prove to be a fleeting optimism about the UN, the

Washington Post

hailed the decision to send the blue helmets. “Peacekeeping is the one activity in the Mideast,” the editors noted, that “the world organization has learned to do well.”

3

3

2

In an editorial that reflected what would prove to be a fleeting optimism about the UN, the

Washington Post

hailed the decision to send the blue helmets. “Peacekeeping is the one activity in the Mideast,” the editors noted, that “the world organization has learned to do well.”

3

Peacekeeping was then loosely defined as the interpositioning of neutral, lightly armed multinational forces between warring factions that had agreed to a truce or political settlement. It was a relatively new practice, initiated in 1956 by Lester Pearson, Canada’s foreign minister, who helped organize the deployment of international troops to supervise the withdrawal of British, French, and Israeli troops from the Suez region of Egypt.

4

Soon afterward the UN Security Council had sent some 20,000 UN peacekeepers to the Congo, where from 1960 to 1964 they oversaw the withdrawal of Belgian colonial forces and attempted (unsuccessfully) to stabilize the newly independent country. Smaller UN missions in West New Guinea,Yemen, Cyprus, the Dominican Republic, and India/Pakistan had followed.

5

The UNIFIL mission in southern Lebanon was given an annual budget of around $180 million. Its 4,000 troops—later increased to 6,000—made it the largest UN mission then in existence.

6

4

Soon afterward the UN Security Council had sent some 20,000 UN peacekeepers to the Congo, where from 1960 to 1964 they oversaw the withdrawal of Belgian colonial forces and attempted (unsuccessfully) to stabilize the newly independent country. Smaller UN missions in West New Guinea,Yemen, Cyprus, the Dominican Republic, and India/Pakistan had followed.

5

The UNIFIL mission in southern Lebanon was given an annual budget of around $180 million. Its 4,000 troops—later increased to 6,000—made it the largest UN mission then in existence.

6

In the three and a half years that had elapsed since UNIFIL’s initial deployment in 1978, Israeli forces had refused to comply with the spirit of international demands to withdraw, handing their positions to their proxy forces, while Palestinian forces had failed to disarm.The resolution establishing the mission had given PLO guerrillas the right to remain where they were.

4

The UN mission’s flaws were thus obvious. The major powers on the Security Council were not prepared to deal with the gnarly issues that had sparked the Israeli invasion in the first place: dispossessed Palestinians and Israeli insecurity. And the Council had given the peacekeepers no instructions as to what to do if the parties continued to attack one another, as they would inevitably do.

4

The UN mission’s flaws were thus obvious. The major powers on the Security Council were not prepared to deal with the gnarly issues that had sparked the Israeli invasion in the first place: dispossessed Palestinians and Israeli insecurity. And the Council had given the peacekeepers no instructions as to what to do if the parties continued to attack one another, as they would inevitably do.

By the time of Vieira de Mello’s arrival in southern Lebanon, command of UNIFIL troops had passed to a second UN force commander: General William Callaghan, a sixty-year-old three-star Irish general who had done UN tours in Congo, Cyprus, and Israel. Vieira de Mello’s main task was to provide Callaghan with the political lay of the land. Because he had lived in Beirut for nearly two years as a boy, Vieira de Mello had long followed events in the region. But once he moved there, he set out to acquaint himself with Lebanese, Israeli, and Western diplomatic officialdom and with the region’s various subterranean militia groups.

He shared an office with Timur Goksel, a thirty-eight-year-old Turkish spokesperson who had been with the mission from the beginning. Goksel gravitated toward what he termed the “gray zones.”“You’ve got to reach out to the men with guns in their hands,” Goksel told his new colleague. “We’ll learn much more from the coffee shops and the mosques than we will from governments.” He brought Vieira de Mello with him to his unofficial meetings. “I have only one requirement,” he said. “You must take off your damn coat and tie!” Vieira de Mello came to understand how essential it was to get to know armed groups such as the Shiite militia Amal, which grew in strength during the early 1980s and would later be largely supplanted by Hezbollah, and the breakaway factions from the PLO, such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, which often fired on UNIFIL peacekeepers. He preferred his informal meetings to those with state officials. He marveled to Goksel, “The UN is such a statist organization. If we played by UN rules, we wouldn’t have a clue what the people with power and guns were plotting.”

Vieira de Mello was amazed at the degree of disrespect accorded to the UN by all parties. UNIFIL had set up observation posts and checkpoints throughout the mission area in the hope of preventing PLO fighters from moving closer to Israel. But the fighters simply stayed off the main roads and used dirt trails to transport arms and men. And because the central Lebanese authorities did not control southern Lebanon, when UNIFIL picked up a PLO infiltrator on patrol, no local Lebanese civil administration existed to press charges. The demoralized UN soldiers simply escorted Palestinian fighters out of the border area and released them. Some found themselves arresting the same raiders again and again.

7

UN peacekeepers who challenged armed Palestinians were regularly taken hostage. On November 30, 1981, just after Vieira de Mello arrived, PLO fighters stopped two UN staff officers, fired shots at their feet, and ridiculed them as “spies for Israel.”

7

UN peacekeepers who challenged armed Palestinians were regularly taken hostage. On November 30, 1981, just after Vieira de Mello arrived, PLO fighters stopped two UN staff officers, fired shots at their feet, and ridiculed them as “spies for Israel.”

The Israelis were equally brazen.They made no attempt to conceal their residual presence. They laid mines, manned checkpoints, built asphalt roads, transported supplies, and constructed new positions on the Lebanese side of the border.

8

Still, because UN officials did not want to offend the most powerful military in the region, they chose not to refer to Israel’s control of the area as “annexation” or “occupation” and complained instead of “permanent border violations.”

9

8

Still, because UN officials did not want to offend the most powerful military in the region, they chose not to refer to Israel’s control of the area as “annexation” or “occupation” and complained instead of “permanent border violations.”

9

The Israeli authorities did not return the favor.They threatened the peacekeepers and regularly denigrated them.

10

Back in 1975 the Israeli public had turned against the UN when the General Assembly—the one UN body that gave equal votes to all countries, rich and poor, large and small—had passed a resolution equating Zionism with racism.

5

Callaghan and Vieira de Mello pleaded with their Israeli interlocutors to cease their anti-UN propaganda, arguing that it was endangering the lives of UN blue helmets, more than seventy of whom had already been killed.

10

Back in 1975 the Israeli public had turned against the UN when the General Assembly—the one UN body that gave equal votes to all countries, rich and poor, large and small—had passed a resolution equating Zionism with racism.

5

Callaghan and Vieira de Mello pleaded with their Israeli interlocutors to cease their anti-UN propaganda, arguing that it was endangering the lives of UN blue helmets, more than seventy of whom had already been killed.

Israel had handed many of its positions to Lebanese proxy forces under a Christian renegade leader named Major Saad Haddad, who delighted in sending Callaghan insolent demands.

6

“I want you to know that tomorrow at 10 a.m., I am intending to send a patrol,” he wrote in a typical message. “I ask for a positive answer.”

11

Whenever the UN peacekeepers got in his way, Haddad simply sealed off the roads in his area, preventing the movement of UN personnel and vehicles. When UN equipment was stolen, which was often, neither Callaghan nor Vieira de Mello could secure its return.

6

“I want you to know that tomorrow at 10 a.m., I am intending to send a patrol,” he wrote in a typical message. “I ask for a positive answer.”

11

Whenever the UN peacekeepers got in his way, Haddad simply sealed off the roads in his area, preventing the movement of UN personnel and vehicles. When UN equipment was stolen, which was often, neither Callaghan nor Vieira de Mello could secure its return.

The PLO had amassed long-range weapons and continued to fire them into Israel; the Israeli army and its Christian proxies regularly retaliated with raids against PLO camps and bases in southern Lebanon.Vieira de Mello’s letters and in-person protestations over the next eighteen months would convey “surprise,”“dismay,” and “condemnation”; they would insist that bad behavior by the Israelis, the Christian proxy forces, and the Palestinians would “not be tolerated”; and they would remind the parties that their transgressions would be “brought before the Security Council.” But because the peacekeepers had neither sticks nor carrots to bring to bear, his protests were generally ignored. Vieira de Mello quickly deduced that the Security Council had placed peacekeepers in an environment in which there was no real peace to keep. As was typical during the cold war, influential governments seemed to be more interested in freezing a conflict in place than they were in trying to solve it. Until the Israelis and Palestinians resolved their differences, or the powerful countries in the UN decided to impose peace, there would be little that a small peacekeeping force could do.

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

10.81Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

Strife by John Galsworthy

Deluded Your Sailors by Michelle Butler Hallett

Forged by Greed by Angela Orlowski-Peart

The Brothers by Sahlberg, Asko

Vertical Burn by Earl Emerson

Déjà Vu: A Technothriller by Hocking, Ian

The Promise Pact (Promise to Love Book 1) by J. A. Fraser

Mystery of the Mummy's Curse by Gertrude Chandler Warner

Faith Hope and Love (A Homespun Romance) by Kakade, Geeta

RecruitZ (Afterworld Series) by Bolton, Karice