Chatham Dockyard (4 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

Worst still, in 1667, the river Medway was subjected to a direct raid carried out by a Dutch squadron of warships. The object was the destruction of both naval warships moored in the river and the dockyard at Chatham. Over a period of four days, the Dutch gradually inched along the Medway, destroying both government facilities and naval warships as they progressed. Having entered the Medway on 10 June, the Dutch squadron had reached as far as Upnor by the morning of 13 June. A number of ships had either been destroyed or captured with the destruction of the dockyard looking inevitable. However, the Dutch, under the command of Vice-Admiral Willem van Ghent, were concerned that an English fleet might well be in the vicinity and could possibly trap them within the river. To avoid this fate, which was not even a developing possibility, van Ghent chose to withdraw, leaving the yard at Chatham to build and repair for another day.

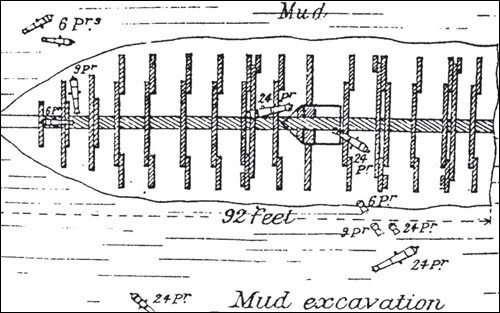

In 1667 the dockyard at Chatham was the ultimate goal of a Dutch squadron that raided the Medway. At the time a number of ships moored in the Medway were sunk, with evidence of one such sunken vessel revealed during the nineteenth century when work was being undertaken on an extension of the yard. Although the remains were not retained, this drawing was made of the find. (TNA Works 41/114)

Upnor Castle, which lies opposite the dockyard at Chatham, played an important part in the defence of the yard at the time of the Dutch raid.

Once again, Peter Pett was viewed with suspicion, described by Pepys as ‘in a very fearful stink for fear of the Dutch, and desires help for God and the King and the kingdom’s sake’.

29

A further witness to the Dutch raid, Thomas Wilson, the Navy victualler, together with his assistant, Mr Gordon, provided members of the Navy Board with a first-hand account of the progress of the Dutch squadron. Somewhere off Gillingham they had seen ‘three ships burnt, they lying all dry, and boats going from men-of-war to fire them’.

30

The unwillingness of the government to pay yard workers their hard-earned wages did not help the situation within the dockyard. In choosing to reject government promises of future payment they chose to withdraw their services during the period of crisis with most seeming to take the view that, if the government would not pay them, then there was no reason why they should risk their lives. According to the Duke of Albemarle, who commanded the English fleet in the Medway, ‘I found scarce twelve of eight hundred men which were then in the King’s pay, in His Majesty’s yard, and these so distracted with fear that I could have little or no service from them’.

31

Once the Dutch retreated the yardmen began to return, but even then they were reluctant to work without wages. To encourage them they were offered a shilling a day extra. According to William Brouncker, a Navy Commissioner, this failed to enthuse them:

But all this stops not the mouths of the yard, who have two quarters [six months’ pay] due to them, and say they deserted not the service but for mere want of bread, not being able to live without their pay. We are fain to give them good words, but doubt whether that will persuade them to stand in the day of trial.

32

The stringent economies and lack of available money to be spent on the dockyard at Chatham were eventually terminated in 1684 when Charles II (1660–85) sanctioned a programme of expenditure that was designed to reverse the sad state into which both the Royal Navy and its support facilities had fallen. For Chatham, plans began to be put in hand for a further extensive enlargement when additional land was acquired, this in two separate purchases, one from the Manor of West Court and the other from the Dean and Chapter of

Rochester. The object was to create sufficient room for two new dry docks built of timber together with a possible enclosed basin that could be used for the more efficient refitting and graving of ships. In the event, only the two dry docks were to be built, these both having a length of 200ft (61m), under very different arrangements. While the workforce of the dockyard constructed one themselves in an attempt to reduce overall costs, the other was built under contract by a certain John Rogers. His tender was for a total payment of £5,310 with estimated time for construction being approximately sixteen months from the signing of the contract. Under James II (1685–88) further improvements to the yard saw the addition of a large brick storehouse situated in the ropery together with ten mast houses. While another round of improvements would undoubtedly have been made if James had remained on the throne, he was usurped after a short reign by the Duke of Orange, who claimed the throne as William III (1689–1702). Equally naval minded, the new King continued to sanction money being spent on Chatham, agreeing to the construction of a second mast pond and a further mast house. Additional stores were also built together with a smithery, painters’ shop and two substantial houses to be occupied by the yard surgeon and his assistant. Finally, with all this new work deemed complete, the original wall of the yard was extended, ensuring that the new mast pond and other facilities were fully secure from the attentions of uninvited visitors.

These important improvements that took place during the latter part of the seventeenth century naturally increased the capacity of Chatham dockyard. Not only that, but it also allowed Chatham to retain its premier position among the royal dockyards. Whereas the other four long-established dockyards, those of Portsmouth, Woolwich, Deptford and Sheerness, could only muster five dry docks between them, Chatham could boast four. Furthermore, Chatham had the addition of a ropeyard with Woolwich the only other yard with such a facility. Finally, through the recent addition of a range of new storehouses and workshops, Chatham was given a further edge over the other naval yards.

Unfortunately for Chatham, however, its supremacy over the other yards was not to remain unchallenged. The new century was to bring a great number of wars, of which France was invariably the enemy. Battlegrounds changed, with the Atlantic and, eventually, the Mediterranean being the future theatres of war. Chatham, in this changing environment, was somewhat ill-placed when compared with the other royal dockyards. Portsmouth began to expand and, within a few years, was able to boast a greater workforce than that of Chatham. Plymouth, an entirely new dockyard, also grew rapidly. Established in 1691, it had, by 1703, a workforce just under half that employed at Chatham. By the middle of the century this had expanded so that it was about equal to that of Chatham.

Not that Chatham ceased to have an important role to perform. Increasingly it was seen as a dockyard more suited to constructing the nation’s warships and less suited to fitting out fleets during times of mobilisation. The result was that many of the nation’s greatest warships – including

Victory

– were to be built there. In doing so, the dockyard at Chatham had lost one role, but was to take on a new and equally important role. As such, it is to this important warship building and heavy repair work to which the rest of this book is devoted, this initial chapter serving only as an introduction to a yard that was to become pre-eminent in its role as the nation’s most important warship building yard.

2

I

N THE

F

OOTSTEPS OF

B

LAISE

O

LLIVIER

On Monday 2 May 1737 Blaise Ollivier, Master Shipwright at Brest, the French government’s most important naval dockyard, passed without restriction into the dockyard at Chatham. Carefully concealing his identity, although his heavy accent and limited knowledge of English clearly marked him out as a foreigner, he was on a very special mission and one that had been sanctioned at the very highest level. His task: that of securing information on working methods used at Chatham and how this compared with those used in the French yards. In other words, Ollivier was a spy, and one who was to report directly to Jean Frédéric, Comte de Maurepas, Secretary of State for the Marine.

That Ollivier was so easily permitted to enter this major military industrial complex might, in this day and age, raise a few eyebrows. After all, Ollivier came from a country with which Britain was frequently at odds, a war breaking out between the two countries only eight years after his infiltration of the dockyard. Yet it was not unusual at that time. Rather than keeping shipbuilding technology a secret, it was often openly shared. The more talented shipwrights sometimes took employment in the yards of other nations, either because they wished to gain a greater range of experiences or had been headhunted and offered a much higher level of remuneration. Certainly, it is known that shipwrights from the British yards had at various times worked in the state yards of Spain, Holland, Russia and Denmark.

1

In turn, the British yards, during earlier periods of their existence, had employed naval shipwrights trained in the arsenal at Venice. Perhaps the best example of this openness to foreign visitors was that of William III giving the Tsar of Russia, Peter the Great (1672–1725), full access to the yard at Deptford. Here, Peter spent a considerable period of time talking to the master builders and making copious notes on both shipbuilding techniques and dockyard procedures. Furthermore, ‘whenever he came into contact with someone he believed could be useful to him, he tried to lure him into service’.

2

As a result, some sixty specialists returned with the Tsar to Russia, these including shipwrights, mast makers, anchor smiths and joiners, all of whom served at the newly created Admiralteiskie Verfi Shipyard in St Petersburg, advising on the facilities and layout necessary for the creation of this yard before going on to lead in the design and construction of a number of large battleships.

3

Given that it was not so unusual for foreign nationals to be given access to a British naval dockyard, this is not the reason for attention being directed towards Ollivier. Instead, it is because of the copious notes that he took, which were turned into a full report that was subsequently submitted to Maurepas. In arriving at Chatham, he cast his professional eye over the activities of the yard, commenting not only upon the unusual and different but also everyday common practice – the type of activities that are difficult for historians to fathom out because nobody sees the point in noting down such occurrences. Furthermore, as the Master Shipwright at Brest, charged with the construction of some of the largest warships being built for a rapidly expanding French Navy, he makes the occasional comparison, indicating whether he considered French or British practice to be superior.

4

On first entering the dockyard at Chatham, Ollivier would have passed under the pedestrian arch of the Main Gate, the same structure that still does duty as the main gateway for those approaching the yard from the town of Chatham. At that time, however, this three-storey brick structure was the only point of entry; all other gates date from the nineteenth century. Completed in 1720, and now known as the Main Gate, its two raised wings at that time provided accommodation for the yard porter and Boatswain of the Yard. Here, Ollivier would have been required to present his letter of authority. Already provided by the Navy Board, this permitted him entry not only into Chatham but all of the other royal dockyards of Deptford, Woolwich and Portsmouth.

Once inside the yard, Ollivier would have followed a well-worn dirt track, the dockyard not at that time having been paved, which took him in the general direction of the Master Shipwright’s office. This was a single-storey wooden building that stood close to the South Dock and provided a convenient location for the Master Shipwright to

observe progress on the repair and building of ships. For purposes of administration, Ollivier had now entered the jurisdiction of the Extraordinary, the part of the yard managed entirely by the Master Shipwright, one of the principal officers of the yard. This area concentrated entirely on the building, repair and maintenance of warships. In addition, there were two other administratively separate areas also headed by principal officers: the ropery, under the charge of the Clerk of the Rope House; and the moorings of the river Medway, known as the Ordinary, and under the authority of the Master Attendant. While the Commissioner of the dockyard coordinated and had a watching brief over all areas of the dockyard, his actual authority was fairly limited and frequently he had to defer to the authority of his principal officers.