Chernobyl Strawberries (26 page)

Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

In the forties, in a room in the coach house which stood in the Japanese garden of Warren House, the Kingston Hill residence of Lady Paget, the Serbian novelist Milos Tsernianski wrote the second volume of

Migrations

, a haunting story of exile and loss, one of the greatest Slavonic books. The Tsernianskis could not afford to pay rent, and repaid their benefactress in kind. Milos, a former Yugoslav diplomat, used his calligraphic skills to address her party invitations and his wife, Vida, baked biscuits for Lady Paget's guests. It is terribly unfair, but I keep thinking of the couple as pets, a pair of Pekinese perhaps. I imagine Lady Paget turning towards one of her friends and saying, against the clinking of porcelain cups, âI keep a Serbian novelist here, you know, my dear.' To his credit, Tsernianski was never a particularly grateful guest: indeed, the veiled references to his hostess in his novels are invariably ironical and bitter. He was a pet piranha rather than a pet Pekinese, biting the hand which fed him. I briefly saw myself in my own coach house at the bottom of Kingston Hill, baking biscuits and writing party invitations, although I no longer had the kind of conceit which would make me feel Tsernianski's equal without having done anything to prove it. On the other hand, I had one enormous advantage

over him. I was free to come and go as I pleased. I needed to feel that freedom in my bones again if I was to survive.

In the early thirties, my Herzegovinian grandfather was visiting Subotica, a town close to the Yugoslav border with Hungary, when he met his future Montenegrin bride. Subotica was the birthplace of James Joyce's Leopold Bloom, a confection of Habsburg neo-Baroque and Jugendstil where poplars and spires still provide the highest points on the cityscape. It is built on land so flat that it tricks the eye into seeing the earth's surface bend and slope off towards the horizon. After the Great War, hundreds of Montenegrins were settled on the farmland around Subotica, in order to firm up the new border of the kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. They continued to yearn for the mountains well into the third generation.

Because of an administrative error, my grandmother's identity card lists Subotica as her birthplace, even though she was born 300 miles further south, in what used to be the kingdom of Montenegro. An educated, well-to-do girl from a good tribe, of which she remained fiercely proud, my grandmother might have married a Sirdar or a courtier. She had raven-black hair and deep-set eyes like sloes. The Great War left her with an invalid father, shipwrecked in the northern plains. She worked in a rope factory to support her younger siblings through school. Surrounded by Hungarian, German and Romanian workers, she picked up words from their languages and for the rest of her life spoke âGranny', a unique Montenegrin-Central European dialect in which Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian layers of vocabulary blended into a singular concoction. No one else in the world spoke this language; her parents were too old to change their speech, her siblings too

young to remember the inflections of the old country. Granny's voice was coarse with asthma â a memento from the years she spent inhaling hemp dust on the factory floor.

I sometimes ring my little sister in her important big office in Toronto and leave a message in âGranny' on her voicemail. I adopt an asthmatic wheeze and let flow a torrent in which complaints and endearments alternate in a linguistic

macédoine

, until I run out of breath and start laughing. My grandmother's rages were biblical, her outpourings of love unmatched. Her way of speaking always seems several sizes too big for me. The telephone line which connects me to my sister's answering machine in the depths of the Canadian winter conveys a code which is more perfect than any my father in his career as a codebreaker ever deciphered. The language of my dead grandmother brings to life all our lost homelands, yet no book has ever been written in it. This is the language I lost when I chose to write books in English, a choice I affirmed when English turned out to be my son's mother tongue. When I capture the code in the language of my son, I'll burn the books and set myself free.

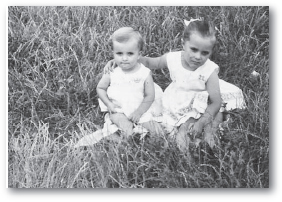

Sisters on the grass

7. Homesickness, War and Radio

ONE OF THE GAMES

my sister and I liked to play when we were children was called âtelevision'. We'd put two chairs side by side at the dining-room table, sit upright and smile beatifically towards imaginary cameras as we shuffled the blank sheets of paper from which we âread' our news bulletins. We had our

noms de plume

, or, rather,

noms de microphone

. âRespected viewers, good evening,' my sister would begin, with the standard opening of Belgrade TV news. âComrade Tito visited a factory today. Over to you, Natasha.' âThank you, Clementine,' I'd say, carefully enunciating every syllable.

My lips were the colour of violets. Before a broadcast we âwent into make-up': early on, we played each other's make-up girls, but then, because of different approaches to aesthetics, each started doing her own. Father had a stash of marker crayons in the garage, red on one side and blue on the other, of an old-fashioned kind which needed a lick in order to write. The crayons made convincing make-up tools: blue for the eyelids, red for the cheeks, a layer of red followed by a layer of blue for the lips, and, only occasionally, a fragrant cloud of Mother's face powder to finish. My sister was fond of fake moles. I hated the way she sometimes read the news looking like a shrunken version of Madame de Pompadour, but I was in no position to choose my co-anchors at that stage. My sister

was the only show in town. While she went on as cheerfully as ever, my growing hostility became apparent in my broadcasts, which I increasingly delivered through clenched teeth.

In those days, news readers on Belgrade television were not really journalists. They tended to be elegant men and women with sonorous, educated voices, selected as much for their political suitability as for their poise and reading skills. News bulletins were static affairs which followed a strict running order. No matter what was going on in the world, Comrade Tito's activities came first. Foreign news could be as bleak as you liked, but home offerings were generally cheerful and positive. Sports achievements followed news of production quotas met and surpassed and the export successes of Yugoslav industry. Contented tourists from around the world visited our coast, and Yugoslav cars raced along the roads of foreign capitals.

It was easy to produce convincing imitations of such daily litanies of success, but they made our broadcasting game repetitive. My sister and I desperately needed excitement and disasters. We occasionally tried to interview our grandmother for the programme, sensing some potential in her story, but she kept rejecting our bids. She never believed anything anyone said in the news bulletins, not even the weather reports, and was indifferent towards the idea of media stardom. Furthermore, she tended to enquire about the nationality of any person who appeared on television, and â if it was a Montenegrin â say something along the lines of, âI knew it. You do not get much more handsome or cleverer than that.' It was only because of her that we noticed that Montenegro, not much more populous than a small British county, produced a disproportionate number of talking heads. This might have had something to do with its beautiful but barren landscape: there was little point in trying to make a go of it at home.

Granny loved agricultural programmes, boxing and Montenegrin folk-dancing â which was itself a convincing imitation of fighting. That was about it as far as television was concerned. She would stay up late watching international boxing championships and always chose her favourites according to their religion. So long as the Orthodox boys won, she was happy; unfortunately, in the world of boxing, that did not happen very often. Mother was exasperated. How could such a seemingly sweet old thing be so fond of savage entertainment and yet cheerfully talk her way through the New Year's Day concert from Vienna which was Mother's favourite TV programme? As far as Mother was concerned, Granny's Montenegrin blood was to blame for all her unladylike excesses.

On those rare occasions when our house filled with those Montenegrin cousins with whom my grandmother was still on speaking terms, and the noise of their arguments became unbearable, Mother would beckon me to the kitchen to help arrange the trays of

meze

. Closing the door behind her, she sighed in resignation. She could never accept the fact that arguing was just the way they communicated. They knew how to keep quiet when they wanted. It was not uncommon to find close relatives living under the same roof who hadn't said a word to each other for ten years because of some tiff the origins of which were long forgotten.

Mother was particularly incensed by Granny's way of dividing people into friend or foe according to their faith, or, rather, according to her perception of it. If one were to believe Granny, the whole of Asia and Africa was âTurkish' and most of the rest of the world Catholic, and we were never quite sure which was worse. The Jews, whom she called

Chivuti

, were great, both because they continued to stand up to the âTurks' and because communist Yugoslavia was hostile to Israel (and anything maligned by that bunch was

ipso facto

fantastic), but

one couldn't quite escape the feeling that that was because she had never really met any Jews, Israeli or otherwise. One thing was certain: we Orthodox folk had to stick together! Not that, in her case, that ever stood in the way of expressing prejudice about Romanians, Bulgarians, Greeks or, in particular, her fellow Serbs. While the Serbs from the highlands were generally OK, those from the lowlands were a bunch of thieves to a man.

My father's mother

How all this annoyed Mother! She was too polite to argue, but she would turn towards Granny and say, âMother, how can you?' in a steady, even tone, using the polite form of

you

. In the thirty years they lived together, my mother preserved the formal

vi â

the Serbian second-person plural â in addressing her mother-in-law, whereas Granny was on familiar,

ti

terms with everyone, including God, with whom she argued

incessantly and loudly as though he were a fellow Montenegrin. âWhy wouldn't you do this for me, God?' she prayed, sounding the word God as though it were a Christian name. âHave I ever thrown a stone at you?'

My sister or I would raise a small, clenched fist â the imaginary microphone â towards Mother's lips, sensing a statement fit for our news bulletins. âYou should never, ever judge people by their faith,' Mother would say, making sure that Granny was within earshot, with examples of wonderful friends who were either Catholic or Muslim at the ready. The older woman shrugged her shoulders and waited for the knockout.