Cherry (52 page)

Picnicking near Lamer: Charlotte Shaw, Pussy Russell Cooke, Cherry, Peter Scott, Kathleen Scott, GBS.

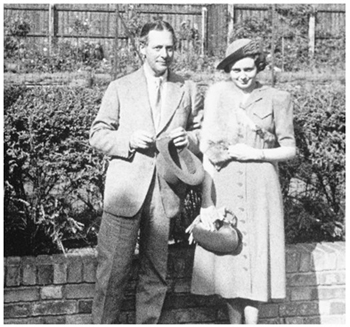

Cherry and Angela on their wedding day.

Cherry in the 1940s, birding on the South Downs.

Cruising (i): 1930s.

Cruising (ii): 1950s.

‘It makes a tale for our generation which I hope may not be lost in the telling.’

Illustrations

Lamer (courtesy of Mr John Gott)

Evelyn Cherry and her son (courtesy of Mrs Angela Mathias)

The Cherry-Garrard family (courtesy of Mrs Angela Mathias)

Culver House at Winchester College, 1903 (Winchester College)

Christ Church 2nd Torpid, 1906 (Christ Church College, Oxford)

Cherry at Lamer (courtesy of Mr John Gott)

The Wilsons and the Scotts at Kirriemuir (Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum)

Assistant zoologist on the

Terra Nova

(Private Collection)

The Southern Ocean (Scott Polar Research Institute)

The

Terra Nova

in the ice (SPRI)

Cape Evans (SPRI)

The Tenements (SPRI)

Dr Edward Atkinson (‘Atch’) (SPRI)

Camping near the Transantarctic Mountains (SPRI)

A sledging party leaves Ross Island (SPRI)

The Barne Glacier (SPRI)

Setting out on the winter journey (SPRI)

After the winter journey (SPRI)

The

South Polar Times

(SPRI)

Scott’s birthday dinner, 1911 (SPRI)

Charles (‘Silas’) Wright (SPRI)

Denis Lillie (SPRI)

The polar party manhauling (SPRI)

One Ton Depôt (Sir Joseph Kinsey Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand)

Man, mule and Emperors (SPRI)

Lieutenant-Commander Cherry-Garrard (courtesy of Mrs Angela Mathias)

Cherry and Angela Turner on their wedding day (courtesy of Mrs Angela Mathias)

Picnicking near Lamer with the Shaws and Kathleen Scott (courtesy of Mrs Angela Mathias)

Birding in the 1940s (courtesy of Mrs Angela Mathias)

Cruising in the 1950s (courtesy of Mrs Angela Mathias)

Cruising in the 1930s (courtesy of Mr Peter Wordie)

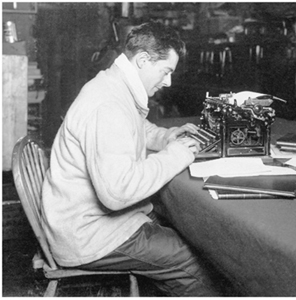

Cherry at his typewriter (SPRI)

Endnotes

1

When Dr Sharpin died in his eightieth year, the local paper ran a long obituary, noting that, ‘In nearly all serious cases in the town in the practice of other medical men, Dr Sharpin was called in when further advice was needed, and many people in his neighbourhood owe their lives to the advice tendered by Dr Sharpin in critical illnesses.’

2

The book was published the year Apsley was born.

3

The Cherrys were solid Tories, but the sentiment applies.

4

Evelyn got out her best gown for dinner at the Salisburys’. Hobbs’ daughter remembered that her mistress chose less splendid attire when dining with Lord and Lady Cavan at Wheathampstead House, though the servants couldn’t decide whether it was because there were dogs in the house, or because the Cavans were merely Irish nobility.

5

Pupils were known as Wykehamists after the school’s founder, William of Wykeham.

6

At the Treasury, Cripps led a ministerial team made up of himself and two other Wykehamists, Hugh Gaitskell and Douglas Jay.

7

Mais was also a prolific book writer. One of his novels,

Caged Birds

, was memorably reviewed in the New Statesman by Rebecca West with the six words, ‘How long, O Lord, how long.’

8

Farrer & Co., still at the same address, are solicitors to the Queen.

9

Now, as a result of boundary changes, in Oxfordshire.

10

Then still Virginia Stephen.

11

The image of a slumbering continent was popular among the first men to land in the Antarctic. The American Frederick Cook, the doctor on the

Belgica

expedition, wrote on his return that with the right backing, ‘The combined armies of peace could . . . march into the white silence, the unbroken, icy slumber of centuries about the South Pole . . .’

12

Peary’s claim has subsequently also been challenged, and he probably didn’t get to the Pole. But at the time it was thought that he had.

13

’This is how it looked,’ wrote Doris Lessing, who grew up in South Africa and was fascinated by Scott’s expeditions, ‘to quite a lot of people not European: there was little Europe, strutting and bossing up there in its little corner, like a pack of schoolboys fighting over a cake.’

14

Finding myself among thirty British men on an Antarctic base eighty-five years later I was gratified to see that nicknames were still going strong. A man with the surname Garrard (no relation) had, pleasingly, been named ‘Cherry’.

15

Nigger was black, with white whiskers on the port side. He was very popular and much photographed, especially after he had mastered a couple of tricks such as jumping through a hoop formed by a man’s arms. When he got a fright and leapt overboard the following year, the ship hove to, a boat was lowered, and the cat saved. In 1912, when the

Terra Nova

was returning from her second journey to the Antarctic, he went up into the rigging one day with the men, as was his custom, and disappeared during a squall.

16

Cherry came to believe that Evans had obtained his position as Scott’s second-in-command through deception. Although Evans surrendered the funds he had raised for his own expedition in exchange for his place on Scott’s, the sum turned out to be far less than he had suggested. Cherry privately accused Evans of ‘[trying] to raise a mutiny’ at Port Chalmers, presumably over the reinstatement of Taff Evans. ‘It seems incredible,’ Cherry wrote furiously years after the event, ‘that Scott should have written (at Port Chalmers) “all is well”.’

17

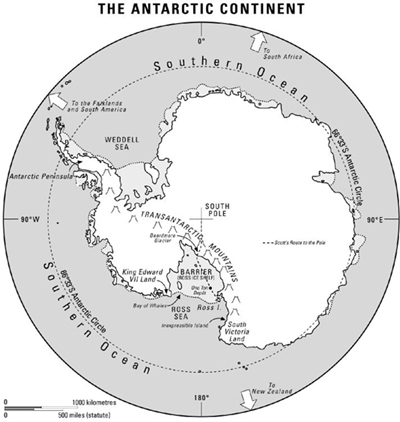

Many floating ice shelves fill embayments (recesses) in the Antarctic coast, all fed by glaciers and ice streams flowing off the land like icing sliding off a wedding cake.

18

‘It is a terrible blow to me that you are seriously thinking about staying out there another year,’ she wrote on 14 May after getting the news.

19

Both sides were apprehensive about this meeting. When the Norwegian watchman spotted the

Terra Nova

he prepared himself for all eventualities by loading his gun with six bullets and looking up ‘How are you this morning?’ in the ship’s English phrase book.

20

The reader may wonder if minus 60 feels any colder than minus 40. My own experience has taught me that it does. Before I went to the Antarctic I glibly assumed that once I had got used to low temperatures it wouldn’t matter terribly if they were in the minus twenties or thirties or forties. I soon learned otherwise. At minus 15 I was able to spend a few minutes repositioning the wire of a radio antenna without gloves. At minus 30 this was a perilous venture: I could manage less than half a minute gloveless before my fingers turned into wooden chipolatas. At minus 45 I could not take any outer gloves off, let alone the polypropylene liners. My lungs hurt when I inhaled such bitter air, my balaclava froze hard to my mouth and I had to massage my nose to prevent the moisture in my nostrils freezing. (Once I threw a mug of boiling tea in the air at around minus 46 and the liquid froze before it hit the ice.) A few degrees made a huge difference to my ability to function, and, as a result, after a few months in the Antarctic I was able to judge the temperature fairly accurately just by standing still.

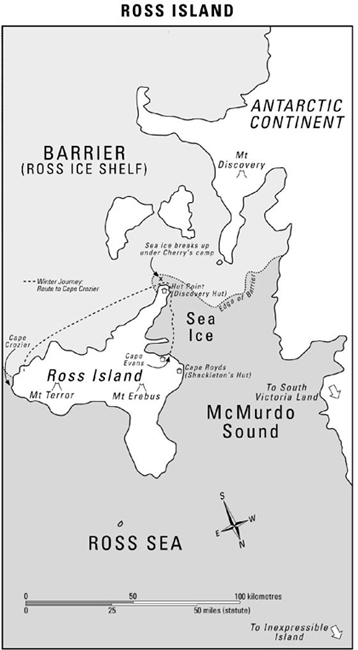

All this, of course, is without wind. A 25-mile-an-hour wind turns a modest ambient temperature of minus 20 into a brutal minus 74 that would freeze exposed flesh in seconds. I once experienced minus 115 with wind-chill at a camp I had at Cape Evans. That day my companion and I had to stay outside for some time anchoring our hut to ensure that it did not go careering off across McMurdo Sound. I can’t recommend it.

21

I was there in February. Flying low over the icefields round Mount Terror, the Texan helicopter pilot pointed down at the gnarled pressure ridges. ‘See those?’ he said over the headset. ‘You could drive a truck through them.’ As for the igloo, a ring of stones about ten inches high had survived. When we landed next to it, the heavy VXE-6 helicopter swung in the wind like a rocking chair.

22

He stuck to his judgement, with one caveat: Scott. ‘The marvellous part of it is,’ Deb wrote, ‘that the Owner is the single exception to a general sense of comradeship and jollity amongst all of us.’

23

Simpson the meteorologist was now universally known as ‘Sunny Jim’ on account of his dashing quiff, which made him look like a popular cartoon figure who appeared on cereal packets.

24

Cherry was annoyed when he read this in Scott’s published diary. ‘Wilson,’ he noted, ‘wrote that I was completely fit.’

25

Wilson thought Scott took Titus because he wanted the army represented at the Pole.

26

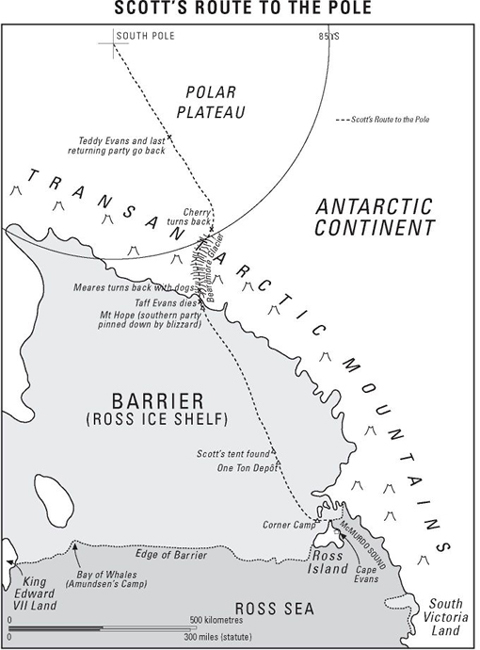

Evans asked Atch if he was going to have to go home on the ship, and the doctor said that he was. Evans was pleased, as before turning round at the top of the Beardmore Scott had ordered him home anyway. (In a letter to Joseph Kinsey, his agent in New Zealand, Scott wrote that Evans had to be sent home ‘as it would not do to leave him in charge here in case I am late returning’.) Evans could now legitimately claim to have been invalided home rather than sent back in disgrace by Scott. Yet Scott had also furnished Evans with a letter of recommendation which duly led to his promotion to the rank of commander. In later years Cherry got in a stew over the role of Evans at this point in the expedition.

27

Near the end, Scott seems to have realised the muddle he had unleashed. When he got to his Mount Hooper depôt and found that the dogs had not been brought that far south, he concluded, ‘It’s a miserable jumble.’ The comment was deleted from the published diary. † Three and a half years later, Dick Richards and other members of Shackleton’s Ross Sea Party found Cherry’s note. The supplies Cherry depôted at One Ton were of incalculable help to them, in a desperate situation themselves: ‘At last we have struck gold in the Antarctic,’ Ernest Joyce wrote that night. So Cherry’s journey was not in vain.

28

In later years Cherry asked a doctor specialising in psychiatric illness about Dimitri, and the man diagnosed hysterical hemiplegia.

29

They probably had died of scurvy, though Cherry was always adamant that this was not the case.

30

During the course of the expedition the Norwegians explored new territory and made significant discoveries. But though they did make meteorological and geological observations, they did not pursue an ambitious scientific programme like Scott’s.

31

It did. I was there eighty-four years later when a small party of Americans repaired it after it had fallen in a blizzard. They re-erected it in a simple ceremony. Cherry would have been pleased.

32

The officers and scientists were also awarded medals by the Royal Geographical Society; the senior navy men were promoted; and Crean and Lashly got the Albert Medal for saving Teddy Evans’ life.

33

Professor Cossar Ewart of Edinburgh University had produced an interim report indicating that the embryos might shed some light on the relationship between scales and feathers. Cherry still believed that an Emperor embryo would reveal the missing link between birds and reptiles.

34

A groundbreaking paper on the spread of Asiatic schistosomiasis, co-authored by Leiper and Atch, was published in the

British Medical Journal

in 1915. With the help of pioneering work by Japanese scientists they had discovered that the parasite entered sailors’ feet while they were swabbing decks. Atch later turned away from parasitology, but Leiper went on to become an international authority on very small worms.

35

In a draft paragraph of

The Worst Journey

that never made it into print he discoursed on how much the Antarctic had to teach ‘the stereotyped respectability of the City Man’. Being in the Antarctic was like climbing a mountain and getting ‘an untrammelled view’ of what before was obscured by clouds and complications. ‘War is another such mountain, but it loses by being artificial, whereas the Antarctic is natural.’

36

Industrial unrest on the home front was all over the papers, notably among the munitions workers on Clydeside.

37

After Shaw’s death Harold Nicolson advised the National Trust that it was morally obliged to accept the house for the nation and to keep it exactly as Shaw left it, ‘as an example of the nadir of taste to which a distinguished writer could sink’.

38

Mysterious to me, I mean.

39

Christabel McLaren (later Lady Aberconway) was a fashionable society hostess and art collector who married Lloyd George’s private secretary. Cherry touched the edges of ‘Society’ through acquaintances like McLaren, but he never entered the fold.

40

‘The two most brilliant theatre geniuses of the first years of this century,’ wrote Sir John Gielgud, ‘were undoubtedly Edward Gordon Craig and Harley Granville Barker.’

41

Shaw, who also spoke out against the maltreatment of conscientious objectors, had cited these two men in an article in the

Nation

.

42

In 1933 Macquarie Island was formally declared a wildlife sanctuary by the Governor of Tasmania.

43

Cherry admired Galsworthy’s work immensely. ‘I’m afraid I’m taking a larger hat,’ he wrote to the author of the Forsyte chronicles after he had praised

The Worst Journey

in print.

44

The largest base in the Antarctic, America’s McMurdo Station, is situated on Ross Island, adjacent to the

Discovery

hut. The summer population of the base can reach 1,500.

45

During the General Strike – class war by any other name – Cherry was astonished to read in

The Times

that the descendants of his armoured cars were patrolling the streets of London, mobilised by their old ally Churchill to keep law and order.

46

Now part of the Lamerwood Golf Course, where hole 10 is ‘Garrard’s Trek’.

47

Glancing from his bedroom window on the eve of a meet, Cherry often glimpsed the flash of a hurricane lamp as the spotter, who lived in a cottage at Lamer Farm, stole through the woods with his brushing hook to block the entrance to the fox earths.

48

Doran merged with Doubleday in 1927, making Doubleday Doran the largest publishing concern in the English-speaking world. Almost fifty years later Dial was also acquired by Doubleday.

49

Emerson said that an institution is the lengthened shadow of a man. The Scott Polar Research Institute, now an internationally renowned centre and the heart of British polar studies, lies in Deb’s friendly shadow. After Cherry died, Deb wrote to his widow, ‘Though I called the work I did over the PRI “in memory of the Pole Party”, it was really in memory of Bill.’ So it should be renamed the Wilson Polar Research Institute.

50

Atch had researched the subject, and shared his conclusions with Cherry. In a draft of

The Worst Journey

Cherry wrote that the polar party had starved, but in the end he held this bald statement back from the public.

51

Charles Webb was a Pooterish figure who for a period ran his wife’s hairdressing shop. He described himself as a hairdresser on Sidney’s birth certificate.

52

Professor Norman MacKenzie, who edited a selection of her letters, concluded, ‘For a well-read and highly intelligent woman the psychological assumptions which underlie her social analysis are astonishingly naïve.’

53

One of these amiable Ponkos turned up at Christie’s recently.

54

The hard-working Frost was relentlessly determined. Working with the American arm of Penguin in the fifties on a new edition of A. J. A. Symons’ classic biography of Frederick Rolfe, she wrote, ‘Even more important than

The Quest for Corvo

is the quest for my stockings and I confirm nine and a half is my size.’ She was later awarded an OBE for services to literature.

55

The second Lord Brocket did little to improve his image when Ribbentrop turned up as a house guest.