Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs (13 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

Ahh, the honesty of little ones.

She wasn’t asking to be mean. She simply wanted to know why this other girl was . . . different . . . different from her and her friends. I crouched down and put my hand on Jaimie’s chest while she stared up at the clouds. She seemed oblivious to the other girl beside me. The inquisitive girl stood astride her bike, staring down at me and waiting for her answer.

I struggled to find the right words to help her understand. “Tell me something. Have you ever tried really hard to do something, but it was really hard for you?”

“Oh, yeah, lotsa times,” she nodded.

“And what happened when you tried to do something hard, and you couldn’t do it right away? How did it make you feel?”

She scrunched up her face, as though it helped her to remember. “I remember learning to ride this bike with no extra wheels, and I kept falling off. I hurt myself a lot. I didn’t want to do it anymore because every time I tried I fell. It made me very mad, and I cried,” she said all in one breath. “My dad and mom told me to keep trying and that I could do it. Then one day, I did!”

“That’s wonderful,” I smiled. “Those mad feelings you felt . . . where you cried . . . didn’t feel very good, did they?”

“No. I didn’t like that.” She looked down.

“That’s how Jaimie feels every single day. The hard part is that what hurts her isn’t always something we can see.”

“You mean something invisible is making her like that?” she asked, her emerald eyes widening.

“I guess you could say that,” I laughed. “You see, Jaimie feels things differently than you or I do. Hey! Have you ever been at the park when it’s really busy and loud?”

“Oh, yes. It’s like that every day at recess,” she said.

“Right! Okay, well, it can get pretty busy there, right? So busy you can’t always concentrate on one thing.”

“Yeah, like if I’m trying to talk to my friends, but everyone is running around and screaming.”

“Exactly. That’s how Jaimie feels all the time. Like there are lots of sounds, things to see, smells, or people trying to touch her, and she gets scared. She doesn’t know how to ignore stuff so she can listen to one noise or see one thing. She gets very scared, and she runs, or she stands there and screams.”

The little girl stared at me for a good minute, then looked down at Jaimie. Her eyes rimmed with tears. “Is that why she ran away from us at the playground?” she asked.

“Yes. It wasn’t because she didn’t want to play with you. There was just too much going on for her to feel comfortable enough to talk to you. That’s all. She’s a wonderful girl to know. You just have to be patient with her until she feels safe enough with you.”

The young girl wiped her nose on her arm, then got back on her bike. “I get scared, too, sometimes. That’s not so weird.”

“No, that’s not so weird.” Jaimie got up and started spinning again. The young girl rode back over to her friends, who asked her why she was talking to “the weird girl.”

As I walked back to the stairs to sit down, I heard the young girl’s voice echo around our complex: “Hey! She’s not weird. Her name is Jaimie, and she’s special. And I’m going to be friends with her.” With that, she dropped her bike, ran back over to our front lawn, and began to spin with Jaimie. “See, Jaimie? There’s nothing wrong with being scared. I’ll spin with you until you want a friend.”

Kids amaze me.

Chynna Laird

Chynna Tamara Laird

lives in Edmonton, Alberta, with her partner, Steve, and three children—Jaimie (four), Jordhan (two), and new baby boy, Xander. She’s a freelance writer, completing a B.A. in psychology. She eventually wants to specialize in developmental neuropsychology to help children and families with special needs. Jaimie has made excellent progress since her diagnosis. Her verbal skills are strong, she loves music and art, and she’s slowly building up her courage to venture out of the boundaries of her strict routine to try new things. She’ll even be attending a special preschool class with her sister, Jordhan, very soon. Please email Chynna at [email protected].

Last year, we went to Niagara Falls and found out that nearby Marineland had orcas. Our son, Sam, has loved killer whales since he was about a year old. The walls in his room are covered in posters and picture calendars of orcas, and we have dozens of orca toys: plastic, plush, large and small, plus magnets, stickers, and pillowcases. And did I mention books? We have countless books on whales and dolphins, but mostly orcas.

Free Willy?

He’s a friend we watch nearly every day.

So off we went to Marineland on Thursday, August 16, 2005. Once in the park, we headed straight for Friendship Cove, home of four orcas. I can’t tell you how excited we all were to watch Sam’s face as he saw, for the first time in his life, a real killer whale. It was a moment to remember, followed by many more that weekend. We purchased tickets to stand with the trainer, and feed and pet an orca.

After a full day of fun with the family at the park, Sam and I returned for a second day—nine hours just standing at the tanks, watching the whales. Sam was in heaven. As we left, he said, “Good-bye, whales. See you next year.”

From the day we departed Canada, Sam started talking about returning on Thursday, August 17, 2006. If you know a child with autism, you know that you have to talk about the upcoming trip daily, like twenty times a day. Fast-forward to this past August. Sam was ready, wearing the same shirt as last year so the whales would recognize him. We got to Friendship Cove, and there were no more ticket sales for feeding the whales! The activity had been replaced with a new Splash Show. Sure, the Splash Show was fantastic and fascinating, but I could see the despair and confusion on my sweet boy’s face. We stayed for two shows, took lots of photos and video, saw the rest of the park, went on rides, and returned to say good-bye to the whales. Sam and I came back again for a second day.

We planted ourselves into position, as we had been last year, to spend the day watching the whales swim around their wide-open tanks. We were literally two feet away from those beautiful mammals. The Splash Show took place every hour and a half. People would start filing into the area ten minutes before showtime, then disperse twenty minutes later, soaking wet.

The trainers noticed we were there—and still there, and again, still there. We started up a conversation with one of the attendants, who asked Sam about the pile of books he was carrying. This young man, Nicholas, recognized that Sam was no ordinary child, and tried to keep him engaged in conversation. One thing became obvious to Nicholas— Sam adored the whales! Then, just prior to the next Splash Show, the “host” of the event, Sean, came over to talk with Sam. I could feel myself leaving my body—you know, that kind of moment you have when something really good is happening. Time stands still, you can barely speak, and tears flood down your face. Sean told Sam, “I could really use a helper for the show. Do you think you could helpme?”

What did he just say? Dear God, thank you.

If I could have felt my legs at that moment, I would have dropped to my knees.

The show began. Mike and Kendra, the whale trainers, introduced themselves to this hysterical mom with winks and smiles. Sean went up to the microphone and introduced Sam Ward from New Jersey. Sam, who had memorized the show, mimicked the trainers. He knew what to do, and he knew the act. The trainers got such a kick out of it! Sam was not afraid in the least to be in front of a huge crowd, and directed the whales to do their tricks. I will be eternally grateful to Nicholas, who had the insight, and to Sean, Mike, and Kendra, who had the hearts, to give this special boy a very special day.

Michelle Ward

Michelle Ward

began her career in architecture, but has been a working artist for ten years. She is a regular contributor to

Somerset Studio

magazine and serves on their editorial advisory board. Michelle and her husband, Graham, live in New Jersey with their three children. And Thursday, August 16, 2007? You know where they’ll be!

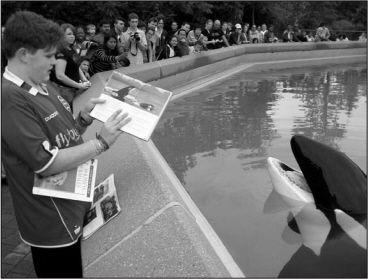

Sam enjoying a good read with a new friend.

Reprinted by permission of Michelle Marie Kelly Ward. ©2006 Michelle Marie Kelly Ward.

B

etter keep yourself clean and bright; you are the window through which you must see the world.

George Bernard Shaw

My nine-year-old daughter, Jessica, is a friendly soul. From the time she was tiny, she would march right up to strangers on the street and say, “Hello!” Her brown eyes would twinkle, and she’d be sporting a big grin on her face. I wish she weren’t so gregarious, because she’s vulnerable. Not only is she young and female, but she also has a disability: she has a cognitive disability, with a debilitating brain disorder that causes autistic and obsessive-compulsive behavior. But that’s also why I’ve done my best to curb my nervousness. Children with autism don’t relate well to others, and I don’t want to discourage her attempts. I worry, though, that people will snub her or be cruel to her, or that she will trust the wrong person.

Happily, in our small town, when Jessica strikes up a conversation with someone, that person almost always responds kindly to her. She never expects to be rebuffed, but I am always waiting, tense, and ready to collect the pieces if it happens. “What’s your name?” she asks total strangers. “Do you have a dog? How old are you?” It always surprises me that people patiently answer her queries. They must sense something about Jessica, that she’s a little bit different. They never seem to expect me to stop her, although I’ve tried.

“We don’t ask adults that,” I say. “That’s a rude question, sweetie,” I tell her, to no avail. She asks anyway, and people tell her. When she is done with her inquisition, she will turn to me and say, “We know Michelle now,” or “That was Mrs. Crawford.” She moves them easily from one category to another: people we don’t know, people we do know. Strangers are merely people she hasn’t yet asked for their names. I’m less sure that finding out their names means we know them. But it’s a small, easygoing town, and I don’t fret too much. It’s not as if she goes about unsupervised or that she tells them anything too personal.

But talking to strangers in our small town is one thing. In New York City, where we visited last year, it’s another. I wasn’t surprised to hear her saying “Hello!” to every single person we saw as we walked the streets of midtown Manhattan, but I certainly wasn’t comfortable. On the first day, I decided not to try to stop her.

This will be a good lesson for her,

I thought.

People will snub her—these are New Yorkers, after all—and then when we get back to the hotel room tonight, she and I will talk about the difference between people in big cities and small towns. And maybe she will learn not to talk to strangers.

But I never got a chance to have my discussion with Jessica. Every single person she said “hello” to said “hello” right back—the businessmen in their somber suits, scurrying from one place to the other; the gawking tourists with their cameras at the ready; the doormen standing at attention in their uniforms. She even said “hello” to the homeless people. She asked what they were doing there, and they told her. I’ve never asked because I don’t talk to strangers. One man on his cell phone stopped in his tracks and told her not only his name and age, but also his occupation and what he was going to do with his girlfriend over the weekend. As he strode off after Jessica’s grilling, I heard him say into the cell phone, “I have no idea who that was. Just a little kid.”

Just a little kid . . . who doesn’t know better than to talk to strangers.

Later, we were at a corner waiting for the light to change, and Jessica greeted everyone there. Over the top of Jessica’s head, I met the glance of a casually dressed man with curly brown hair. “She’s autistic, isn’t she?” he said to me, with a directness that took my breath away. After all, he was a perfect stranger. I put my hand protectively on Jessica’s shoulder. “Yes,” I said. This is the kind of encounter I dislike, but I wasn’t telling him anything he didn’t already know.