Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs (31 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Soul: Children with Special Needs Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

On Halloween 1992, we were going to a nightclub in our costumes. She was Catwoman, and I was a gypsy. A car ran a red light, hitting us head-on. Sarina went through the windshield, and I was a mess—broken knees and hands, and a fractured skull. Sarina sustained no injuries but a scratch on the nose and neck.

When we were discharged from the hospital, I could barely walk and was in constant pain. Sarina had to cook, assist me in the shower, help me get dressed, and do my hair—basically everything I had done for her previously. She was amazing! She had retained all that I had taught her and was able to apply it to real-life situations, not only for herself, but also for another. We had switched roles—I was now being taken care of by my sister.

After five years, I decided to move back to the New England area. Sarina and I climbed Calico Basin in Las Vegas on Christmas day, and when we got to the top I told her that I wanted to go back. She very clearly said to me with a smile, “You go, my sister. I stay here.”

I asked her who would take care of her, and she said, “I take care of myself.” I had little doubt she could, but I just couldn’t leave her alone in Las Vegas, so she gave in and moved back to New England with me. After we got settled, she got her own apartment with twenty hours of assistance and took college classes.

I will never forget how I wondered if I could take care of Sarina. Now I wonder if I could have accomplished all I did if I didn’t have her in my life. She has shaped my career, my personality, my parenting skills, and my life. I love you, my sister.

Gina Favazza-Rowland

Gina Favazza-Rowland

is a holistic counselor in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and a case manager for folks with “different abilities,” not disabilities. She is currently writing a book about Sarina and their lives together. Sarina and Gina each have their own My Space account—feel free to look the mup at

www.myspace.com/gypseahealer

and

www.mspace.com/angelface38

!

“He’s ruining my life,” Clayton yelled as he ran upstairs to his bedroom and slammed the door. Clayton was talking about his younger brother, Bennett, who resides in the same bedroom. The two boys share not only their room, but also their clothes, toys, friends, and, on occasion, underwear.

As I followed Clayton upstairs, I glanced at the Lego tower he had just finished building. It was now in pieces, and in the middle of the destruction was, of course, Bennett, quietly gathering up all the red Lego pieces.

“How is Bennett ruining your life?” I asked Clayton.

“He follows me everywhere. He ruins our games. He growls too loudly in my ear. He won’t let me sleep at night. He breaks my stuff. He’s just ruining my life!”

Bennett entered our family when Clayton was three years old. Clayton didn’t have to share much with his little brother for the first year. But after Bennett’s first birthday, he moved into Clayton’s room. Bennett was still in his crib, and Clayton slept in a bed. Three feet of space separated the two sleeping boys. At night, I could hear Clayton sing songs to his little brother and attempt to tell him stories with his limited speech. In the morning, I would find Clayton’s favorite stuffed animals scattered in the crib with Bennett. Very often, Clayton would be in there, too.

We soon moved to a bigger house with an extra bedroom, but we decided it was best to keep the two boys together. That was also the same month that Bennett

turned three and was diagnosed with autism.

The boys continued to play somewhat independently. Bennett was content to play dinosaurs by himself, leaving Clayton to his own friends, and games of Legos and Pokémon. Then, one day, Bennett became Clayton’s unshakable shadow, stuck fast to his back, front, side, and even his head.

That’s when Clayton first declared, “Bennett’s ruining my life!”

My husband and I just smiled, thinking we knew how he felt since both of us had had to share a room with a younger sibling who ruined our lives as well. My own childhood memories didn’t stop me from forcing our two boys to spend every waking moment side by side. My voice could often be heard encouraging their twosome. “Include Bennett. Let Bennett play. Let him take a bike ride with you. Let him go outside with you. Share your pop. Give him a cookie. Let him hold your Pokémon cards. Let him have all the red Legos. Give him the frog.”

Clayton obliged most of the time, albeit begrudgingly, and I knew there was little he could do on his own as long as Bennett was around.

I thought I knew how he felt since I had a little sister who was my shadow for eighteen years. One night, I found out how little I knew about how he felt.

I had just put the boys down for bed and was settling into my book and a bowl of popcorn when I heard what sounded like crying from the upstairs bedroom.

I sighed and hesitantly climbed the stairs. “What are you crying about?” I demanded angrily. Clayton had used the crying stall tactic many times at bedtime.

“I . . . I . . . I . . . wahhhh!”

“What? Slow down, I can’t hear what you’re saying,” I said, softening my voice and sitting down on his bed.

“I just wish Bennett had a different brain . . . wahhh!”

That’s when my heart sank in my chest. I had never realized until that moment what a burden my oldest son was carrying as he tried to be a big brother to Bennett.

“Why do you wish Bennett had a different brain?” I asked, sincerely wanting to know how he felt.

“I just get so mad at him, and then I feel so bad because I know he can’t help it. It’s just not fair that I can’t have a normal brother who understands things like I do.”

My throat tightened, and tears filled my eyes. I knew exactly what Clayton was talking about. I knew how Bennett’s disability had impacted me, but I had never really thought about how it had impacted his siblings.

I rubbed Clayton’s back softly as he continued to sob. “Do you know why Bennett was given to our family?”

“Yes, I know. So that I could protect him, and that he could teach us and others to love people who are different than us. I know. I know. But I still wish he had a different brain and that he didn’t have autism.”

“Do you think he knows that we love him even when we get mad at him?”

“Yes,” Clayton said, sitting up and looking over at Bennett, who was playing on his bed unaware that a conversation about him was happening just three feet away. Bennett continued to crash his plastic dinosaurs together, making gnashing and gnarling sounds as they wrestled on top of the bedspread.

“Benny, do you want to sleep in my bed tonight?” Clayton asked with tears still staining his cheeks.

Bennett grabbed his pillow, his blanket, and twenty toy dinosaurs, and crawled onto the foot of Clayton’s bed, curling himself around his big brother’s feet.

“I love you, Benny,” Clayton said.

“I wove you, Benny,” Bennett replied.

After tucking the boys in for the “this is the last time, and I mean it” time, I pondered Clayton’s words and realized he needed some time away from Bennett. He didn’t know how to say it and probably didn’t even realize he needed time off from being “Big Brother.”

I found babysitters for Bennett so Clayton could spend some uninterrupted time with Mom and Dad. I also arranged more play dates for Clayton away from home. Clayton still gets angry and frustrated with his little brother, but he knows when he needs time alone that he can ask. When Clayton comes to me and says, “I need to be alone,” I find a special spot for him to be alone with his thoughts and his Legos. After a little while, he returns, looking for Bennett, who greets him with a toothless smile.

The boys still share their clothes, their bedroom, and their toys. But as this mother found out, they don’t always need to share their time. They needed time off from being full-time brothers.

And at the end of the day, when the lights are out, I still hear two brothers at the end of the hall, trying hard to whisper as they fly their toys off the end of the bed and battle plastic dinosaurs until they fall asleep, sharing a bed and possibly each other’s underwear.

Kimberly Jensen

Kimberly Jensen

is the mother of three children, and writes children’s books focusing on loving children. Today, Clayton and Bennett have separate bedrooms after a move to a new house and a heartwarming essay by Clayton entitled, “A Room of My Own.” That essay solidified Kimberly’s decision to separate her growing boys after reading the line where Clayton expressed the need for “a room to be me.” Please e-mail Kimberly at [email protected].

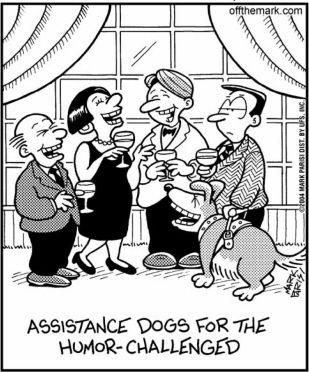

My husband and I are the good-humored parents of four children with autism. Not many people come to visit, but when they do, they are sometimes surprised at what they may experience. One day, a repairman came to our house. Upon seeing our 110-pound dog, he fearfully asked if the dog bites.

My eleven-year-old son with Asperger syndrome said to him, “No, our dog is very well behaved and does not bite. However, you may want to make sure that you do not get too close to my three-year-old brother. He has sensory problems, and biting is his way of checking you out. So if he gets too close, run.” At that moment, our three-year-old was in the process of biting the dog, who just looked at me as if to say, “Please, help me. The toddler is biting me again.”

The repairman, looking a bit surprised, commented that our dog was very well behaved indeed.

Deana Newberry

Deana Newberry

received her master’s degree in Spanish education from the University of Buffalo in 1994. She is a teacher in western New York. She is currently completing a Spanish lesson book for her special-education students. You can email her at [email protected].

off the

mark.com

Reprinted by permission of Off the Mark and Mark Parisi. ©2006 Mark Parisi.

I

sn’t it splendid to think of all the things there are to find out about? It just makes me feel glad to be alive—it’s such an interesting world.

Lucy Maud Montgomery,

Anne of Green Gables

T

here are two ways of exerting one’s strength:

one is pushing down, the other is pulling up.

Booker T. Washington

I have worked with people with disabilities since I was in college. Honestly, though, I have always said, “This really isn’t where I belong.” I did not study special education in college. I was a psychology major. When I pursued my master’s degree, I chose early-childhood education hoping to open a parenting center in my community to teach expectant parents the wonders of newborns and very young children.

Yet, time after time, I kept finding jobs and opportunities in the field of developmental delays and disabilities. My husband and I were blessed with two little girls when I was working as the director of an early-intervention program for children from birth to age three with developmental delays and disabilities. My young daughters were raised around a kitchen table where stories were shared about the triumphs, challenges, joys, and struggles of parenting children with disabilities. They heard many of my “soapboxes” about stereotyping people with disabilities. They cried or laughed at wonderful stories from those infants and toddlers and their families who opened their lives to me.