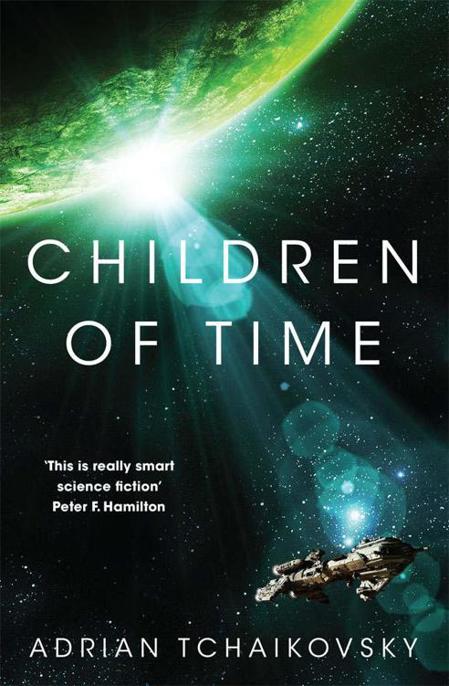

Children of Time

Dear Reader,

Thank you for buying this book. You may have noticed that it is free of Digital Rights Management. This means we have not enforced copy protection on it. All Tor ebooks are available DRM-free so that once you purchase one of our ebooks, you can download it as many times as you like, on as many e-readers as you like.

We believe that making our Tor ebooks DRM-free is the best for our readers, allowing you to use legitimately-purchased ebooks in perfectly legal ways, like moving your library from one e-reader to another. We understand that DRM can make your ebooks less easy to read. It also makes building and maintaining your digital library more complicated. For these reasons, we are committed to remaining DRM-free.

We ask you for your support in ensuring that our DRM-free ebooks are not subject to piracy. Illegally downloaded books deprive authors of their royalties, the salaries they rely on to write. If you want to report an instance of piracy, you can do so by emailing us:

[email protected]

.

Very best wishes,

The Tor UK team & our authors

To Portia

2.1 TWO THOUSAND YEARS FROM HOME

2.5 ALL THESE WORLDS ARE YOURS

3.12 A VOICE IN THE WILDERNESS

5.5 THE OLDEST MAN IN THE UNIVERSE

6.2 AN OLD MAN IN A HARSH SEASON

6.6 AND TOUCHED THE FACE OF GOD

GENESIS

1.1

JUST A BARREL OF MONKEYS

There were no windows in the Brin 2 facility – rotation meant that ‘outside’ was always ‘down’, underfoot, out of mind. The wall screens told a pleasant fiction, a composite view of the world below that ignored their constant spin, showing the planet as hanging stationary-still off in space: the green marble to match the blue marble of home, twenty light years away. Earth had been green, in her day, though her colours had faded since. Perhaps never as green as this beautifully crafted world though, where even the oceans glittered emerald with the phytoplankton maintaining the oxygen balance within its atmosphere. How delicate and many-sided was the task of building a living monument that would remain stable for geological ages to come.

It had no officially confirmed name beyond its astronomical designation, although there was a strong vote for ‘Simiana’ amongst some of the less imaginative crewmembers. Doctor Avrana Kern now looked out upon it and thought only of

Kern’s World

. Her project, her dream,

her

planet. The first of many, she decided.

This is the future. This is where mankind takes its next great step. This is where we become gods.

‘This is the future,’ she said aloud. Her voice would sound in every crewmember’s auditory centre, all nineteen of them, though fifteen were right here in the control hub with her. Not the true hub, of course – the gravity-denuded axle about which they revolved: that was for power and processing, and their payload.

‘This is where mankind takes its next great step.’ Her speech had taken more of her time than any technical details over the last two days. She almost went on with the line about them becoming gods, but that was for her only.

Far too controversial, given the

Non Ultra Natura

clowns back home

. Enough of a stink had been raised over projects like hers already. Oh, the differences between the current Earth factions went far deeper: social, economic, or simply

us

and

them

, but Kern had got the Brin launched – all those years ago – against mounting opposition. By now the whole idea had become a kind of scapegoat for the divisions of the human race.

Bickering primates, the lot of them. Progress is what matters. Fulfilling the potential of humanity, and of all other life.

She had always been one of the fiercest opponents of the growing conservative backlash most keenly exemplified by the

Non Ultra Natura

terrorists.

If they had their way, we’d all end up back in the caves. Back in the trees. The whole

point

of civilization is that we exceed the limits of nature, you tedious little primitives.

‘We stand on others’ shoulders, of course.’ The proper line, that of accepted scientific humility, was, ‘on the shoulders of giants’, but she had not got where she was by bowing the knee to past generations.

Midgets, lots and lots of midgets

, she thought, and then – she could barely keep back the appalling giggle –

on the shoulders of monkeys.

At a thought from her, one wallscreen and their Mind’s Eye HUDs displayed the schematics of Brin 2 for them all. She wanted to direct their attention and lead them along with her towards the proper appreciation of her – sorry,

their

– triumph. There: the needle of the central core encircled by the ring of life and science that was their torus-shaped world. At one end of the core was the unlovely bulge of the Sentry Pod, soon to be cast adrift to become the universe’s loneliest and longest research post. The opposite end of the needle sported the Barrel and the Flask. Contents: monkeys and the future, respectively.

‘Particularly I have to thank the engineering teams under Doctors Fallarn and Medi for their tireless work in reformatting –’ and she almost now said ‘Kern’s World’ without meaning to – ‘our subject planet to provide a safe and nurturing environment for our great project.’ Fallarn and Medi were well on their way back to Earth, of course, their fifteen-year work completed, their thirty-year return journey begun. It was all stage-setting, though, to make way for Kern and her dream.

We are –

I

am – what all this work is for.

A journey of twenty light years home. Whilst thirty years drag by on Earth, only twenty will pass for Fallarn and Medi in their cold coffins. For them, their voyage is nearly as fast as light. What wonders we can accomplish!

From her viewpoint, engines to accelerate her to most of the speed of light were no more than pedestrian tools to move her about a universe that Earth’s biosphere was about to inherit.

Because humanity may be fragile in ways we cannot dream, so we cast our net wide and then wider . . .

Human history was balanced on a knife edge. Millennia of ignorance, prejudice, superstition and desperate striving had brought them at last to this: that humankind would beget new sentient life in its own image. Humanity would no longer be alone. Even in the unthinkably far future, when Earth itself had fallen in fire and dust, there would be a legacy spreading across the stars – an infinite and expanding variety of Earth-born life diverse enough to survive any reversal of fortune until the death of the whole universe, and perhaps even beyond that.

Even if we die, we will live on in our children.

Let the NUNs preach their dismal all-eggs-in-one-basket creed of human purity and supremacy

, she thought.

We will out-evolve them. We will leave them behind. This will be the first of a thousand worlds that we will give life to.

For we are gods, and we are lonely, so we shall create . . .

Back home, things were tough, or so the twenty-year-old images indicated. Avrana had skimmed dispassionately over the riots, the furious debates, the demonstrations and violence, thinking only,

How did we ever get so far with so many fools in the gene pool?

The

Non Ultra Natura

lobby were only the most extreme of a whole coalition of human political factions – the conservative, the philosophical, even the diehard religious – who looked at progress and said that enough was enough. Who fought tooth and nail against further engineering of the human genome, against the removal of limits on AI, and against programs like Avrana’s own.

And yet they’re losing

.

The terraforming would still be going on elsewhere. Kern’s World was just one of many planets receiving the attentions of people like Fallarn and Medi, transformed from inhospitable chemical rocks – Earth-like only in approximate size and distance from the sun – into balanced ecosystems that Kern could have walked on without a suit in only minor discomfort. After the monkeys had been delivered and the Sentry Pod detached to monitor them, those other gems were where her attention would next be drawn.

We will seed the universe with all the wonders of Earth.

In her speech, which she was barely paying attention to, she meandered down a list of other names, from here or at home. The person she really wanted to thank was herself. She had fought for this, her engineered longevity allowing her to carry the debate across several natural human lifetimes. She had clashed in the financiers’ rooms and in the laboratories, at academic symposiums and on mass entertainment feeds just to make this happen.

I,

I

have done this. With your hands have I built, with your eyes have I measured, but the mind is mine alone.

Her mouth continued along its prepared course, the words boring her even more than they presumably bored her listeners. The real audience for this speech would receive it in twenty years’ time: the final confirmation back home of the way things were due to be. Her mind touched base with the Brin 2’s hub.

Confirm Barrel systems

, she pinged into her relay link with the facility’s control computer; it was a check that had become a nervous habit of late.

Within tolerance

, it replied. And if she probed behind that bland summary, she would see precise readouts of the lander craft, its state of readiness, even down to the vital signs of its ten-thousand-strong primate cargo, the chosen few who would inherit, if not the Earth, then at least this planet, whatever it would be called.

Whatever

they

would eventually call it, once the uplift nanovirus had taken them that far along the developmental road. The biotechs estimated that a mere thirty or forty monkey generations would bring them to the stage where they might make contact with the Sentry Pod and its lone human occupant.

Alongside the Barrel was the Flask: the delivery system for the virus that would accelerate the monkeys along their way – they would stride, in a mere century or two, across physical and mental distances that had taken humanity millions of long and hostile years.

Another group of people to thank

, for she herself was no biotech specialist. She had seen the specs and the simulations, though, and expert systems had examined the theory and summarized it in terms that she, a mere polymath genius, could understand. The virus was clearly an impressive piece of work, as far as she could grasp it. Infected individuals would produce offspring mutated in a number of useful ways: greater brain size and complexity, greater body size to accommodate it, more flexible behavioural paths, swifter learning . . . The virus would even recognize the presence of infection in other individuals of the same species, so as to promote selective breeding, the best of the best giving birth to even better. It was a whole future in a microscopic shell, almost as smart, in its single-minded little way, as the creatures that it would be improving. It would interact with the host genome at a deep level, replicate within its cells like a new organelle, passing itself on to the host’s offspring until the entire species was subject to its benevolent contagion. No matter how much change the monkeys underwent, that virus would adapt and adjust to whatever genome it was partnered with, analysing and modelling and improvising with whatever it inherited – until something had been engineered that could look its creators in the eye and understand.