China Witness (56 page)

Authors: Xinran

The policewoman who had acted as go-between and set up our meeting was clearly also moved by the openness and courage of the old officer. She had said she would do everything in her power to help us in our survey of the real China of today, to help the future understand the uncertainties of today and the price paid in the past. In fact, without her help, how would I ever have found this outstanding PSB officer, since he had already been consigned to limbo?

As we said farewell to Henan, the policewoman presented me with her personal case notebook and the newspaper clippings she had put together for our survey, as a memento. I only realised after reading them that she had made me another gift too. There was a sheet of paper tucked into the back of her notebook:

Ten very sad stories: From this mountain, I cannot see our present era clearly.

*24

1.

I want to go home, I want my wages!

This was the last thing Yue Fuguo, a worker, said before he died. After these words, he suffered a cerebral haemorrhage and lost consciousness. Thirty-six hours later, the hospital reported that he had died. Yue Fuguo had still not received the wages that were due to him. The grief-stricken widow, Yao Yufang, asked indignantly: "How could they not pay him?" (Reported in

Chengdu Commercial News

)

People say: When his parents named him "wealthy nation" [fu-guo], little did they imagine that he would not succeed in making even himself wealthy.

2.

I will never abandon my dream of going to Beijing University.

Because her university entrance exam results had not given her the number of points required to get into university, Xiao Qian (not her real name), a seventeen-year-old from Shaanxi, threw herself from the balcony of her fifth-floor home. A week later she died, and after her death, reporters found a note in her room which read:

I will never abandon my dream of going to

Beijing University

. Her leap, however, put paid forever to her dream. (Reported by Xinhuanet)

People ask: Are you happy, children of China?

3.

What are you actually doing?

It was the small hours of 18 May 2004, and Chang Xia was still asleep, when five police officers and an informer erected a ladder and broke in through the window of her flat. A stunned Chang Xia plucked up the courage to ask them who they were. "They" wanted Chang Xia to "hand over that man who did it with you". Eventually they discovered that, apart from the uninvited guests – themselves – there was no one else there, whereupon they said, somewhat sheepishly, that they "might have got the wrong person". Still thunderstruck, Chang Xia asked again: "Who are you, and what are you actually doing?" but "they" simply swaggered out. Looking through the window, Chang Xia saw their car number plate. The fright they had given her unbalanced her mind. She mutters over and over to herself: "The car number plate, I remember it, those people, the middle of the night, they climbed in through the window, they were looking for someone, they searched my flat . . ." (Reported in

Shenyang Today

)

People ask: West of the Taishan Mountains, there's a saying which goes: "Wind and rain may get in, but the King of China cannot get into my house." But now there's no one to ensure people's privacy.

4.

He went to the Great Wall but was drowned by the waters.

The "he" here refers to Zheng Jinshou, a young labourer from Fujian province working in Beijing. He and his girlfriend Xu Zhenjie were interrogated by the Civil Defence while meeting in the park, and were beaten up for not having their documents with them and for refusing to pay a fine for not having them. Zheng Jinshou staggered blindly off in panic and,

as he was injured, ended up falling into the river and drowning. After his death, his girlfriend said: "He used to quote the saying that 'to be a real man you have to get to the Great Wall', but he went there and the waters took his life." His elder brother, Zheng Jinzi, said: "My brother was a strong swimmer, he was an athlete at school. If he hadn't been beaten almost unconscious, he definitely wouldn't have drowned." (Reported by Digital Media)

People say: To misquote Confucius: to think that the Civil Defence may take more lives than venomous snakes do!

5.

I wanted that child.

When being interviewed, Ma Weihua said quietly: "I wanted that child." Ma Weihua had been arrested as a drug dealer. She was pregnant at the time and, according to the law, the death sentence could not be carried out on a pregnant woman so, without her permission, the police authorities anaesthetised her and carried out an abortion. Afterwards the police spokesman said that they suspected that Ma Weihua had become pregnant deliberately, in order to avoid the death sentence. (Reported by

South Weekend Review

)

People say: No comment.

6.

You go to school now, Mum's got to be off . . .

When Huihui was born a girl, her father abandoned the family. For seven years, her mother endured all kinds of hardships to bring up her daughter. However, she was not a very capable worker, and life was indescribably hard. For seven years, she had not had any new clothes, for seven years, she had lived off pickled vegetables. If she did happen to buy a fish, she gave it to her daughter to eat. Even so, on Huihui's birthday every year, her mother would always buy her a birthday cake. But this year, Huihui's mother just couldn't get together the 100 yuan, so when Huihui had gone to school, her mother hanged herself. (Reported by

Anhui Market News

)

People say: A harmonious society, huh!

7.

If you didn't force me, would I volunteer to go out and sweep snow in the

streets?

Sun Fengmei is a blind girl. After a snowfall, the local area committee asked Sun Fengmei to "volunteer for snow-sweeping" under threat of removing her minimum living standard benefit from her. When news of this got out, they changed their tune and said that even if she didn't, they

still couldn't take away her benefit. At the same time, they absolutely deny that they ever said she had to sweep snow or they would remove her benefit. But Sun Fengmei asks: "If you didn't force me, would I volunteer to go out and sweep snow in the streets?" (Reported by

Shengyang Daily

)

People say: It seems as if "volunteering" is often used as the opposite to its real meaning.

8.

I'm wearing my best clothes

.

Putting on his convict's uniform, Ma Jiajue said: "I'm wearing the best clothes I've ever had." Police officers who heard him say this could not help shedding a tear. Ma Jiajue was a murderer, but the law could not take into account how he had grown up. When his school grant was not approved, Ma was so poor that he did not dare go to school because he had no shoes to wear. His schoolmates remembered that, after this, his character completely changed, and he stopped talking to anyone. (Reported by

Souhu Cultural News

)

People ask: Don't the poor also have their dignity?

9.

By the time you read this, son, I won't be alive any more

. . .

"Son, when you read my letter, I won't be alive any more, because I'm not capable of getting you into school, and I can't face you. Only with my death can I truly apologise to you . . ." When the son of Sun Shoujun, a Liaoning peasant, received his school placement letter, his father had no money to send him. So he left a suicide note to him and killed himself. (Reported by Xinhuanet)

People say: Don't say stuff like if you don't go to university, you can still make a good life for yourself. Even comedian Stephen Chow's screen characters know everyone's desire to go to school gives you a way of deceiving people.

10.

I could have put up with it for three more days

.

Guan Chuanzhi is a miner. He was trapped in a mine shaft during a mining accident, where he survived for seven terrible days. The first thing he said when his rescuers brought him out into daylight was: "I could have put up with it for three more days." (Reported by

Nanjing Morning News

)

People ask: Brother miners, good brothers, how long will you have to put up with this?

Will Chinese law become the sticking point in China's progress to a democratic future? I know a lot of Chinese people are asking, and waiting,

but we need many more Chinese people who will work hard for the law, like old Mr Jingguan.

On 30 December 2006, I had just edited the second draft of

China Witness

to this point, when I got a phone call from the BBC World Service

World

Today

programme, asking me to join a discussion on some news from the Xinhua News Agency in China:

On 1 January 2007, the

Supreme People's Court is to implement a policy requiring ratification by the Supreme People's Court of all death sentences handed down by lower courts. This is a historically significant step in the development of Chinese criminal law, not only for China's criminal justice work, but also for the progress

and development of the Chinese legal system.

With regard to criminal cases, China operates a system of the Court of Second Instance being the Court of Last Instance. Judicial review of death sentences falls outside the First and Second Instance system, and there are special procedures set up which are targeted at death penalty cases. After New China was established, the policy of retaining and strictly controlling the death sentence was implemented and the ratification system for death sentences was set up. In 1954, regulations on the organisation of the

People's Courts were issued and these decreed that death penalty cases must be ratified by the Supreme People's Court and the

Higher People's Courts. In a decision made at the fourth session of the First People's Congress in 1957, all death-penalty cases were thenceforth to be decided or ratified by the Supreme People's Court. Between 1957 and 1966, all death penalties were ratified by the Supreme People's Court.

During the Cultural Revolution, the People's Courts came under heavy attack, and the system of ratifying death sentences ceased to operate except in name. In July 1979, the second session of the Fifth National People's Congress passed the

Chinese Criminal Code and Criminal Procedure Law, revising the organisation of the People's Courts. It was decreed that all death sentences other than those passed by the Supreme People's Court, must be approved by the latter. However, in February 1980, not long after the Chinese Criminal Code and Criminal Procedure Law had been passed, another decision was passed by the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress, with the aim of meting out swift and severe punishment to criminal elements who had seriously jeopardised the social order: the Supreme People's Court thereby authorised Higher People's Courts to handle some death-sentence

cases for a limited period. Following further reforms of the organisation of the People's Courts, and repeated delegation of authority, this system has persisted up to the present day.

My first reaction was to telephone Mr Jingguan. I hoped I would hear him say: Finally the Supreme Court has reclaimed the right to confirm the death sentence, and removed it from the hands of muddled and incompetent judges who indiscriminately execute the innocent! But when I called him, just before the Spring Festival in 2007, to send him and his family season's greetings, and we talked about the new legislation, the old policeman said: "These are just words on paper, miles away from the heads of the people who deal with the cases. It's only when everyone is capable of understanding the significance of those words that people will understand the law, and the law enforcers will no longer dare persist in their reckless ignorance. How many people has China tortured? How many 'Clear Sky Baos' are there?"

From the first Qin emperor of China, and the first law to operate on the principle that "the nine clans bore responsibility for the misdemeanours of their members", to a China, two thousand years later, which has just emerged from political adversity, the ghostly wails of the countless wrongly accused, victims of corrupt local officials who use their power to trifle with human lives, echo down the centuries. In two thousand years of Chinese history, for all our boasting about our ancient political and judicial system, there has only been one great judge, the Song dynasty's Justice

"Clear Sky Bao", known to every Chinese for his uncompromising honesty. Just one.

The Shoe-Mender Mother:

28 Years Spent out in All Weathers

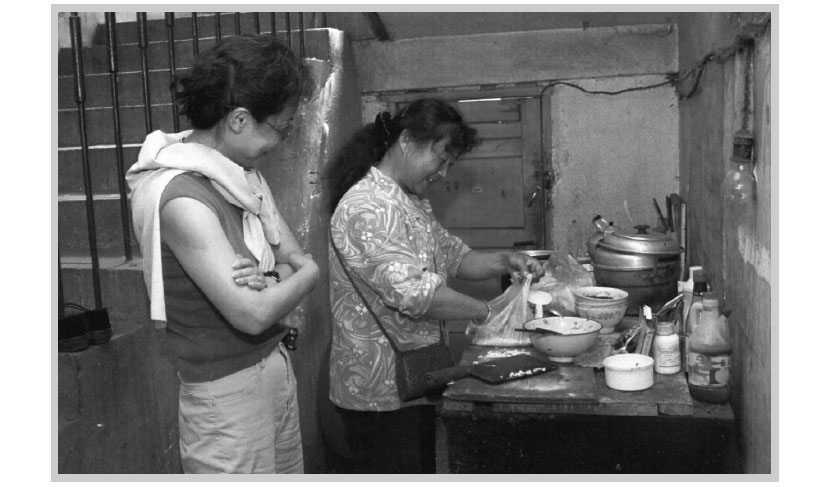

The shoe-mender woman, Zhengzhou, was at first shy of our camera . . .

. . . but later invited us home for lunch.