Chinese Fairy Tales and Fantasies (Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library) (5 page)

Read Chinese Fairy Tales and Fantasies (Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library) Online

Authors: Moss Roberts

Suddenly he remembered that he was carrying a bag of fox-bane at his waist. Prying it free with two fingers, he broke open the bag and spilled the poison onto his palm. Then, turning his neck so that he could see his opened palm, he let the blood drip from his nose onto his palm. In moments his hand was full. The serpent drank a little of the poisoned blood, whereupon its body uncoiled, its tail thrashed with a peal like thunder, and it knocked against the tree, cracking the tree in half. Then it lay down on the ground and died, looking like a huge beam.

At first Chang was too faint to get to his feet, but in an hour or two he revived enough to load the serpent on his boat and row home. It was more than a month before he fully recovered from the attack by the beautiful girl who was a serpent spirit.

—

P’u Sung-ling

A Girl in Green

A student called Sung from Yitu, Shantung, was studying in the Temple of Sweet Springs. One night when he was reciting aloud over his open books, a girl appeared outside his window. “How diligently young master studies,” she said admiringly. As Sung wondered how such a maiden came to dwell in the mountain depths, she had already come smiling into the room. “Such diligence!” she repeated. Sung rose, surprised. She was graceful and dainty, green-bloused and long-gowned. Though he sensed that she might not be human, Sung questioned her about her home town.

“Can’t you see I’m not going to bite you? Why bother with all these questions?” she replied.

Greatly attracted, Sung shared his bed with her that night. When she took off her gossamer jacket, her waist was so slender that two hands could enclose it. Later, as the last night drum sounded, she fluttered away and was gone.

She came every evening after that. Once when they were having wine together, her conversation revealed a knowledge of music. “Your voice is so bewitching,” Sung said. “If you would compose a song it would melt my heart.”

“For that very reason,” replied the maiden, “I must not sing.” He pleaded, and she explained, “Your serving maid would not begrudge you the song, but what if someone should hear? Still, if you insist, I can only show my poor skills—just a whispered sign of my affection.” As she sang, she tapped her tiny foot lightly upon the couch.

No butcherbird must catch

This slave girl’s midnight song.

No chill night dew can stay me

From keeping my lord company.

Her voice was a fine hum, the words barely audible. But to the absorbed listener the movement of the melody was lissome and ardent, affecting the heart as it touched the ear.

When the song was over, she opened the door and peered outside. “I must make sure no one is out there.” She looked all around Sung’s chamber before reentering.

“What makes you so anxious?” he said.

“The proverb ‘A ghost that steals into the world fears all men’ applies to me.” Then she went to bed, but she was still uneasy. “The end of our relationship may be at hand,” she said. Sung pressed her for an explanation. “My heart is restless,” she told him. “I sense danger. My life will end.”

Sung tried to calm her. “Such flutters of the heart are normal,” he said. “Do not jump to conclusions.” The maiden seemed relieved, and they embraced again.

When the water clock had run dry and it was morning, the maiden put on her clothes and got out of bed. She was about to open the door, but walked back and forth instead. Finally she returned to him. “I don’t know why,” she said, “but fear is in my heart. Please see me out.” The youth arose and escorted her outside. “Keep an eye on me,” she said. “You may go back after I get over the wall.” Sung agreed. He watched as she rounded the corridor, then could see her no more.

Sung was about to return to bed when he heard her cry out desperately. He rushed toward the sound, but there was no sign of her—only a noise under the eaves. Looking carefully, he saw a spider the size of a pellet with something in its clutches that made a whining sound. Sung broke the web, picked out the object, and removed the threads that bound it. The captive was a green bee on the verge of death. He took it to his room, where it rested on his desk for a long while. When the bee was able to walk, it slowly climbed to the inkwell and pitched itself in. Then it crawled out and walked back and forth until it had formed the word “Thanks.” The bee stirred its wings and with a last effort flew out of the window, ending the relationship forever.

—

P’u Sung-ling

Butterfly Dreams

Chuang Tzu said, “Once upon a time I dreamed myself a butterfly, floating like petals in the air, happy to be doing as I pleased, no longer aware of myself! But soon enough I awoke and then, frantically clutching myself, Chuang Tzu I was! I wonder: Was Chuang Tzu dreaming himself the butterfly, or was the butterfly dreaming itself Chuang Tzu? Of course, if you take Chuang Tzu and the butterfly together, then there’s a difference between them. But that difference is only due to their changing material forms.”

—

Chuang Tzu

Suited to Be a Fish

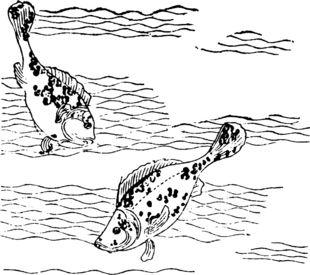

Hsüeh Wei was appointed deputy assistant magistrate in Ch’ing-ch’eng county in the year

A.D

. 759. He was a colleague of the assistant magistrate, Mr. Tsou, and the chief constables, Mr. Lei and Mr. P’ei. In the autumn of that year Hsüeh Wei was ill for seven days. Then he suddenly stopped breathing and did not respond to persistent calling. But the area around his heart was slightly warm, and the family, reluctant to bury him too quickly, stood guard over him and waited.

Twenty days later, Hsüeh Wei gave a long moan and sat up. “How many days was I senseless?” he asked.

“Twenty days.”

“Find out for me whether or not the officials Tsou, Lei, and P’ei are now having minced carp for dinner,” Hsüeh Wei said. “Tell them I have regained consciousness and that something most strange has happened. Bid them lay down their chopsticks and come to listen.”

A servant left to find the officials, who were indeed about to dine on minced carp. He conveyed Hsüeh Wei’s request, and they all stopped eating and went to Hsüeh Wei’s bedside.

“Did you gentlemen order the revenue officer’s servant, Chang Pi, to get a fish?” Hsüeh Wei asked them.

“Yes, we did,” they replied.

Hsüeh Wei then turned to Chang Pi and said, “Chao Kan, the fisherman, had hidden a giant carp that he had caught; he offered to fill your order with some small fish instead. But you found the carp in the reeds, picked it up, and brought it back. When you

entered the magistrate’s office, the revenue officer was sitting east of the gate; one of the sergeants was sitting west of the gate. The revenue officer was in the midst of a game of chess. As you entered the hall, Mr. Tsou and Mr. Lei were gambling. Mr. P’ei was chewing on a peach. When Chang Pi told them how the fisherman had withheld his fine catch, they had him flogged. Then they turned the fish over to the cook, Wang Shih-liang, who was delighted with the carp and killed it. Is not all this true?”

The officials turned and consulted one another and confirmed everything, saying, “But how did you know?”

“Because that carp you had killed was me!” Hsüeh Wei replied to the astounded group.

“Tell the whole story,” everyone said.

“When I first took sick,” Hsüeh Wei began, “the fever was so intense that I could hardly bear it. All at once I felt stifled and forgot that I was ill. Burning as if I had caught fire, I sought to cool myself. I began to walk with a staff in my hand, unaware that I was dreaming.

“When I had gone past the city wall, an ecstatic mood came to me, as if I were a caged bird or beast gaining its liberty. No one could know how it felt! I made my way into the hills, but I felt more stifled there than before. So I went down to wander by the edge of the river. It was deep and quiet, like a pool. The autumnal quality of the water made my heart ache. Not even a ripple was moving, and the water mirrored remotest space. Suddenly I had a desire to enter the water. I left my suit of clothes on the bank and dove in.

“Ever since my youth I have been fond of the water, but in adulthood I no longer went swimming. Now I felt eager to enjoy myself so freely and satisfy a long-held desire. But I thought to myself, ‘Swimming in the water, man is not as fast as fish are. I wonder if I could enter somehow into the life of a fish and swim rapidly?’