Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States (25 page)

Read Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States Online

Authors: Andrew Coe

Mechanical pianos, fixtures in many chop suey joints by World War I, propelled some Chinese restaurant owners into a new phase of business. These machines were the jukeboxes of their day: you put a nickel in the slot, and the piano’s mechanism played fox-trots, jazz tunes, and popular songs. Unsettled by one such piano’s “whang and pulse,” the members of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union chapter in Hammond, Indiana, drilled holes in the floor of the apartment above the King Honk Low restaurant and poured dirty mop water onto the patrons in 1913. The mechanical piano’s quick rise to popularity soon inspired

entrepreneurial restaurant owners to bring entertainment—music, dancing, and a floor show—into their establishments. (They had been best known as

after

-theater joints.) One of the earliest of these new nightclub-restaurants was the Pekin, at Broadway and Forty-seventh Street, which a 1916 New York City guidebook listed as “an elaborate Chinese show restaurant; cabaret, music, dancing.”

11

This trend only accelerated when the Volstead Act banning the sale of alcoholic beverages went into effect in early 1920. In the first years of Prohibition, tens of thousands of restaurants and nightclubs across the nation, from Manhattan lobster palaces to Los Angeles cantinas, went out of business. Chinese restaurants, however, thrived, because they had never served alcohol—tea had always been their most potent beverage.

By 1924, Broadway between Times Square and Columbus Circle was home to fourteen big “chop suey jazz places.” One Chinese nightclub owner, a former Essex Street laundryman, supposedly wore a huge diamond ring, rode in an imported car, and squired around a bottle-blond burlesque dancer. In San Francisco, most of these new nightspots were in Chinatown, probably beginning with Shanghai Low in the 1920s. Featuring all-Chinese singers, musicians, chorus lines, and even strippers, clubs like the Forbidden City attracted a clientele of politicians, movie stars, and businessmen out for an exotic good time. In smaller cities, the entertainment at Chinese restaurants, still revolving around the player piano, was more modest. On Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue, the heart of the African American district, the Lum Pong Chop Suey Place had the danceable “I’ll Be Glad When You Are Dead, You Rascal You” cued up on the piano.

Nearly all of these Chinese restaurant-nightclubs catered strictly to mass tastes; there was never a Chinese version of El Morocco or the Stork Club. A 1934 New York restaurant guide describes Chin Lee’s, one of the largest of these joints at Broadway and Forty-ninth Street, as “chop suey chef to the masses and dispenser of dim lights, ceaseless dance music, undistinguished floor shows, and tons of chow mein.” As for its patrons, they were young, numerous, and hungry:

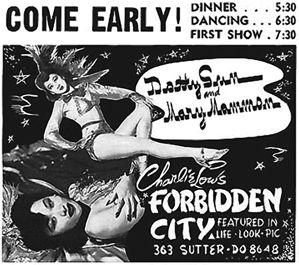

Figure 6.2. From

1938

to

1962,

San Francisco’s Forbidden City nightclub featured performances by Asian-American musicians, dancers, strippers, and magicians. Performers were given such nicknames as the “Chinese Sinatra” to attract non-Chinese clients.

Here at any hour of the day, from eleven to midnight, you may find the girl who waits on you at Gimbel’s, her boy friend, who is one of Wall Street’s million margin clerks, noisy parties of Bronx handmaidens babblingly

bent on a movie and subgum spree, college boys from Princeton (slumming, of course), and, perhaps, even your next-door neighbor. Within the not-so-occidental confines of Chin’s, the girls dance with other girls, and the boys dance with anyone handy. The prices are scaled down to suit the toiling thousands, and Chin Lee’s offers its clientele, for 55 cents or 85 cents, their idea of a $5 floor show. Though their idea may be a bit vague and thin, the customers seem to like it and applaud lustily between mouthfuls of fried noodles and oriental onions.

12

These restaurant owners were all too aware that they weren’t selling caviar and champagne but chop suey, ham and cheese sandwiches, and the like—food everybody liked but nobody wanted to spend much money on. The real profits were in volume and in liquor; the businessmen rented the largest possible spaces and featured a wide array of exotic cocktails on their menus.

The specialties of the Chinese American menu, from chop suey to moo goo gai pan to pepper steak, eventually lost their exotic associations. In his 1916 novel

Uneasy Money

, P. G. Wodehouse listed chop suey among the “great American institutions,” up there with New Jersey mosquitoes, the Woolworth Building, and corn on the cob. In big cities like New York, the most popular Chinese restaurant dishes had become everyday food:

[Chop suey] has become a staple. It is vigorously vying with sandwiches and salad as the sometime nourishment of the young women typists and telephonists of John, Dey and Fulton Streets. It rivals coffee-and-two-kinds-of-cake as the recess repast of the sales forces of West Thirty-Fourth Street department stores. At lunch hour there is an eager exodus toward Chinatown of

the women workers employed in Franklin, Duane and Worth Streets. To them the district is not an intriguing bit of transplanted Orient. It is simply a good place to eat.

13

In midwestern towns like those Sinclair Lewis used as models for Gopher Prairie, Chinese food probably held on to its mystery through the 1930s. (For small-town sophisticates, the local Chinese restaurant was often the only eatery where they could find both glamour and late closing hours.) Beyond these establishments, chop suey was now served in soda fountains, coffee shops, school cafeterias, military messes, church suppers, and even Manhattan’s ultrasophisticated Stork Club (whose version was made with wild rice, butter, celery, spinach, and big rib steaks). Forty years after its appearance on Mott Street, chop suey had become cheap, fun, and filling American food.

Americans’ embrace of chop suey was impelled by more than the assemblage of ingredients, style of preparation, and lingering whiffs of the far-off East: chop suey penetrated the larger culture, mutating and changing its meaning depending on the context. Cookbooks gave housewives one way to prepare chop suey and other Chinese dishes, but soy sauce, bean sprouts, and the like remained hard to find outside big cities. By 1915, regional companies like Chicago’s Libby, McNeil & Libby had started canning chop suey and selling it in grocery stores; apparently, these products were bland and unappealing and didn’t really take off. In 1920, two men in Detroit, Wally Smith and Ilhan New, began growing bean sprouts in Smith’s bathtub and canning them. Within four years, their company, which they named La Choy, had a whole line of canned Chinese foods on the market: bean sprouts, mushrooms, crispy chow mein noodles, Chinese vegetables (mixed water chestnuts and bamboo shoots), “Chinese Sauce” (soy sauce), and “Brown Sauce,” a kind of savory, molasses-based gravy. The labels claimed you could now make “genuine Chop Suey or Chow Mein in ten minutes.” According to the millions of recipe booklets La Choy distributed, all you had to do was fry up some meat, onions, and celery; mix in La Choy vegetables; spoon in the Chinese Sauce and Brown Sauce; and serve the resulting stew over rice or chow mein noodles. Semi-homemade chop suey tasted better than the canned version, and La Choy soon dominated the grocery aisles. (Now owned by ConAgra Foods, it remains the leader in canned Chinese American provisions today.)

Figure 6.3. The

1916

menu for the Oriental Restaurant in New York’s Chinatown contains dishes like birds’ nest soup and sharks’ fins, as well as “chop sooy” and chow mein.

In the early twentieth century, chop suey also took a lexical jump from Chinese restaurants onto other kinds of menus—a testament to its penetration of the culture. Soda fountains began offering “chop suey sundaes,” described as “chopped dates, cherries, figs, raisins, citron and different kinds of nuts, all forming a cherry colored syrup, [and] poured over a round allowance of cream; then . . . sprinkled with more nuts.”

14

Two decades later, this concoction had become a mélange of chopped tropical and fresh fruits flavored with cherry syrup and served over ice cream with sliced bananas, nuts, and whipped cream. “American chop suey,” another faux version of the dish, was invented around the same time. The

Alton

(

IL

)

Evening Telegraph

called the Chinese dish “the high water mark of the delicacy” and then described the American version as perhaps more satisfying to less sophisticated appetites. Here’s the recipe:

Place in a spider a lump of butter, size of a walnut; in this, when hot, brown one and one-half pounds of Hamburg steak; heat a can of tomatoes, fry four medium-sized onions, and boil two cups of macaroni or spaghetti; seasoning each article well; drain macaroni and add it, with the onions and tomatoes, to the meat, and simmer five minutes. No side dishes are needed if this is made for lunch, as it makes a palatable, substantial lunch for six or seven people.

15

Home cooks in rural New England and the Midwest today still prepare nearly the same recipe—filling food for

hardworking people. As the writer for the

Evening Telegraph

admitted, chop suey was just another word for hash.

Away from the restaurant counter and home dinner table, the practitioners of the other popular arts also embraced chop suey as a concept. As early as 1900, Chinese food was considered fun and lively, with plenty of mass appeal. Why not throw it into a song, a movie, or a vaudeville show? That year, chop suey was the centerpiece of a twenty-four-second short entitled

In a Chinese Restaurant

. Produced by the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company, it showed the Bowery personality Chuck Connors and two Chinese men seated at a table and eating chop suey while having an animated conversation—a scene of intercultural fraternization that probably shocked many in the audience. Over the next few decades, Chinese restaurants appeared in a number of movies, usually as the quintessential urban, working-class eatery—the kind of place where hard-bitten showgirls discussed their men, or the cop fell in love with the gangland moll. A few of these films also played with the old white slavery stereotypes. In Harold Lloyd’s 1919 short

Chop Suey & Company

, a heroic but hopelessly naïve policeman becomes convinced that evil Chinese are plotting to abduct a young woman eating in a chop suey joint. After many gags, it’s revealed that she’s really an actress rehearsing scenes for a play. Others traded in chauvinism, like Gale Henry’s 1919 comedy

The Detectress

, featuring special glasses that allow a character to see what’s really in chop suey: dead dragonflies, rope, the sole of a shoe, and a puppy. One of the rare films to apply these stereotypes more seriously to the Chinese restaurant setting was the 1930 potboiler

East Is West

, starring Lew Ayres. In it, young Ming Toy (played by Lupe Vélez!) is rescued from slavery and brought to San Francisco, where she attracts the attention of evil Charlie Yong (Edward G. Robinson), the city’s chop suey kingpin. In the nick of time, they discover that Ming Toy

isn’t Chinese at all but the child of white missionaries and can finally marry Lew Ayres after all. (The

New York Times

reviewer noted that even pulp magazines would hesitate to publish such a trashy story.)

Race also figured in some of the early song lyrics that referred to Chinese food. The 1909 “Chink, Chink, Chinaman,” by Bert Williams, a popular African American vaudeville performer, begins: “One time have chop suey house / on street where heap white boys, / all time sing ‘bout chink chink chinee / all time make heap noise.” The narrator decides to move to the African American neighborhood but discovers that even there the residents sing “Chink chink chinee.” By the 1920s, these stereotypes had become stale and overused, at least in their most blatant form. The era’s most popular dance was the jazz fox-trot, inspiring tunes like the 1923 “Hi Lee Hi Lo—I Love You Chop Suey a la Foxee” and Louis Armstrong’s famous “Cornet Chop Suey,” an instrumental with a bright and lively melody. Two years later, Margaret Johnson recorded Sidney Bechet’s humorous “Who’ll Chop Your Suey When I’m Gone?”