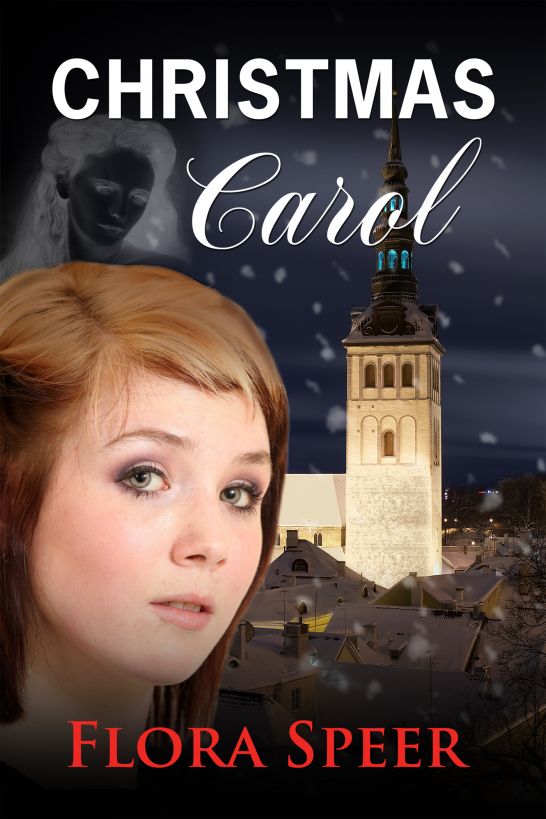

Christmas Carol

By Flora Speer

Smashwords Edition

Published by Flora Speer at Smashwords

Copyright © 1994, by Flora Speer

Cover design Copyright 2012, By

http//:DigitalDonna.com

This book is dedicated to my readers, and

most especially to those who enjoy historical, time-travel, or

futuristic romances. We who read or write in those subgenres of

romance believe that true love is not confined by the limits of

ordinary time or space. Thus, I give you Carol’s story, with the

wish that every one of your holidays will be merry and bright and

that love, which is the true spirit of any holiday, will remain in

your hearts throughout all the years to come.

All the best to you,

Flora Speer

Humbug.

London, 1993

.

Considering her dislike of any occasion that

required the distribution of gifts or money, it was regarded by all

who knew her to be perfectly in character for Lady Augusta Marlowe

to take her leave of this world on the 18th day of December. By

doing so she neatly avoided having to hand out Christmas presents

to her servants or to the few tradespeople who were still willing

to deliver groceries, or wine or spirits, or the occasional

garment, to her door. That is to say, to the door assigned for

servants and tradesmen. The front door—original to the house and

carved of solid oak—was seldom used anymore. Even Carol Noelle

Simmons, who was Lady Augusta’s paid companion, and thus might have

passed with impunity through the mansion’s chief portal had she

chosen to do so, almost always used the servants’ entrance instead.

However, on Tuesday, the twenty-first day of December, Crampton the

butler was kept busy opening and closing the heavy front door, for

this was the day of Lady Augusta’s funeral.

Carol was forced to admire the old girl’s

spunk. Early in the autumn Lady Augusta had declared with all the

shrill force of which she was capable that she

would not

be

taken to a nursing home or to a hospital. She absolutely defied her

despairing physician on that point. Nor, as it turned out, did she

intend to pay for professional nursing care at home. Thus, it had

fallen to Carol and the few remaining servants to bathe and feed

her, and to turn her when she became incapable of moving on her

own.

Lady Augusta’s fury at her ever-increasing

helplessness had fallen upon all of her staff, but most especially

on Carol. Cantankerous to the end, during the last few months of

her life Lady Augusta had even denied Carol the free day each week

that she was supposed to have.

While not daring to disobey her employer,

Carol had resented the deprivation. She had precious little money

to spend—Lady Augusta considered room and board to be a large part

of her servants’ wages and Carol was, in Lady Augusta’s opinion, no

more than an overpaid servant—but London offered pleasures that

cost nothing at all. The only requirements were a comfortable pair

of walking shoes, an umbrella, and a weatherproof outer garment.

But since Lady Augusta had become permanently bedridden at the end

of September, Carol’s solitary walks had been denied to her. Those

treasured hours could soon begin again, for Carol stood now, in

late afternoon of the day of Lady Augusta’s funeral, in the chilly,

pale yellow drawing room of Marlowe House, bidding farewell to the

mourners.

There were few of them and they departed

ill-fed. When she knew her end was fast approaching, Lady Augusta

had stipulated that only tea and biscuits should be served at the

funeral “feast.” Even in death her commandments were not to be

disobeyed. Carol wondered if the servants feared Lady Augusta would

return to haunt them if they opened a bottle of sherry for the

guests as she herself had suggested the day before.

“Certainly not, Miss Simmons,” Crampton had

responded to Carol’s remark with barely concealed horror. “There

will be no wine served. Lady Augusta personally ordered the menu

for this occasion and we will, as always, follow her directions to

the letter.”

And so they had. A small coal fire burned in

the grate, a plate of biscuits and a pot of tea sat upon a tray on

one of the delicate Regency-style tables, and Carol felt certain

the drawing room was every bit as cold and cheerless as it must

have been in the early eighteen hundreds when Marlowe House was

first built.

Now the Reverend Mr. Lucius Kincaid, who was

the rector of nearby St. Fiacre’s Church and who had performed the

funeral service, approached Carol. Assuming that he was about to

take his leave, Carol put out her hand to shake his. But the

clergyman apparently had no intention of departing from Marlowe

House until he had extracted some information from Carol.

“I do hope,” he said, “that Lady Augusta

remembered St. Fiacre’s Bountiful Board in her will.” He was a

tall, thin man with dark hair going gray and clothes that did not

fit him very well. Carol regarded him with distaste for, like her

late employer, she was not interested in religion. In fact, Carol

could not remember Lady Augusta ever entering a church. It was

Crampton who had suggested that the Reverend Mr. Kincaid be asked

to conduct the funeral service.

“We have not yet heard anything about Lady

Augusta’s charitable bequests,” said the rector’s wife, who joined

them. In contrast to her nondescript husband, the blond, blue-eyed

Mrs. Kincaid wore a fashionable outfit with a remarkably short

skirt and a hat that might have come right out of the American

West. “I must confess that we at St. Fiacre’s are feeling a bit

desperate right now. There always seems to be such need at

Christmastime, so much that ought to be done to help the poor. We

stand ready to provide what is required, if only we have the funds.

Or at least a pledge.”

“I am not authorized to make donations in

Lady Augusta’s name,” Carol said coldly. “If you want money, speak

to her solicitor.”

“Then perhaps you yourself would care to

contribute to our holiday efforts,” urged the rector, giving Carol

a smile she chose not to return.

“I do not,” Carol snapped.

“Surely,” Lucius Kincaid persisted, “having

received from Lady Augusta generous recompense for your devoted

care of her over these last five years and more, you will be

disposed at this holy season to give liberally to help the less

fortunate.”

Biting her tongue to keep herself from

retorting that there was no one less fortunate than herself, Carol

glared at the Reverend Mr. Kincaid. Until meeting him on the day of

Lady Augusta’s death she had not known that people stiff talked the

way he did. With his cultivated accent the man sounded as if he

belonged in the Victorian Age. How dare he hit her up for money at

a funeral?

“St. Fiacre’s Church,” Carol murmured, taking

a nasty pleasure in what she was about to say. “I know who St.

Fiacre was.”

“In this nation of gardeners, most people

do,” the rector responded, “since he is the patron saint of

gardeners.”

“That’s not all,” said Carol. “St. Fiacre was

a typical woman-hating, sixth-century Irish hermit-monk. As I

recall, he made a rule forbidding all females from entering his

precious enclosure.” She was not sure why she was deliberately

being so unpleasant. She usually had better manners than she was

displaying on this occasion, but something about the Kincaids

grated on her. For a reason she could not understand, they were

making her feel guilty. She did not like the feeling.

“Saints are notoriously difficult people,

whose very saintliness makes everyone around them uncomfortable,”

Mrs. Kincaid said, laughing as if to show she was not offended by

Carol’s rudeness. “There is even a legend about a noblewoman who

once broke St. Fiacre’s rule. She actually dared to walk into the

enclosure surrounding his hut and attempted to speak with him. Of

course, she immediately suffered a dreadful death. But that

happened, if it happened at all, more than fourteen hundred years

ago. It would take a foolish woman indeed to still be angry over

attitudes that existed so far in the past. In these modern times,

we ought instead to forgive poor old St. Fiacre his sins, if any,

against the gentler sex, and perhaps occasionally invoke his

horticultural spirit when we are having trouble with our gardens.”

She finished her speech with a smile.

“I don’t garden,” Carol said. “I never have.”

She watched with pleasure as Mrs. Kincaid’s smile vanished.

“If you would like to learn,” Lucius Kincaid

offered in a friendly way, “we can always put volunteers to good

use in the little garden in our churchyard when spring arrives.” •

“No, thanks. I’m a city girl.” The Kincaids would probably expect

her to donate plants to their wretched garden. Carol had no

intention of throwing any money away on

flowers

.

“Look,” Carol said, “it’s none of your

business, but just so you won’t waste your time asking me again,

Lady Augusta left me nothing.”

“Nothing at all?” gasped the rector’s

wife.

“Nothing.” Carol was still reacting with

rudeness to what she perceived as prying questions. “Since you

appear to be indecently interested in the will, let me tell you

what the solicitor told me and the

other

servants this

morning. Lady Augusta did leave small amounts to Crampton and to

Mrs. Marks, the cook. But Nell the chambermaid, Hettie the scullery

maid, and myself receive nothing but room and board for one month

after Lady Augusta’s death, during which time we are to search for

new employment.”

“Dear me.” The rector appeared to be in

shock. “Not a generous arrangement, I must say.”

“You’re damned right about that. I hope you

weren’t expecting Lady Augusta to be generous.” Carol included both

the rector and his wife in her mirthless grin. “She was the

stingiest, coldest woman I nave ever known.”

“Now, now, Miss Simmons,” Lucius Kincaid

said. “Whatever your personal disappointment in this matter, one

must always speak well of the dead.”

“That’s what I was doing. I admired Lady

Augusta’s stinginess, and the way she never took any nonsense from

anyone. She lived and died the way she wanted and I say, good for

her.”

“She lived for the most part alone, and died

alone, too, save for her employees,” the rector noted, adding in

one of his old-fashioned phrases, “One would hope to have at one’s

side at the end of life a close relative, or at least a dear

friend.”

“Instead she had me, and she didn’t think I

was worth much. She proved that by her non-bequest.” Carol did not

add what she was thinking, that everyone else she had ever known

had also assumed that Carol Noelle Simmons wasn’t worth much. Not

unless she had plenty of money to boost her charms into something

interesting. She made herself stop thinking about her own past. She

had promised herself long ago to put out of her mind the uncaring

man who—

“Speaking of close relatives,” said the

rector’s wife, intruding into Carol’s unpleasant ruminations, “why

isn’t Nicholas Montfort here? I believe he is Lady Augusta’s only

living relative?”

“Yes,” her husband put in. “Mr. Montfort is

Lady Augusta’s nephew, her only sister’s child.”

With an effort, Carol refrained from asking

if her two inquisitors had been researching the Marlowe-Montfort

genealogy. Instead, she offered a reasonably polite explanation for

the absence of Nicholas Montfort.

“Mr. Montfort was unable to leave Hong Kong

immediately. Business interests keep him there. He sent a telegram

urging us to go on with the funeral in his absence. He expects to

arrive in London sometime next week to meet with the solicitor

about the estate.”

“One would think,” said the rector’s wife,

“that he would have wanted the funeral delayed until he could be

present.”

“No doubt Mr. Montfort was as fond of his

late aunt as were most people.” Carol’s eyes narrowed as she

addressed the rector. “Come to think of it, I never noticed

you

visiting Lady Augusta while she was alive. Would you

have asked

her

for a donation?”

“I did, during a pastoral visit several years

ago. She refused to give any money to St. Fiacre’s and said she

never wanted to see me in her house again. Still, in Christian

charity, one would have thought—in her will—and here it is

Christmastime.…” Lucius Kincaid paused meaningfully.

“Oh, yes.” Carol could not keep the sneer out

of her voice. In truth, she did not try very hard, for her

exasperation with this ecclesiastical couple was increasing

rapidly. “The holiday. I am afraid I would be the last person to

help you in the name of the season. I don’t think much of

Christmas.”

“Not think much of Christmas?” Mrs. Kincaid

echoed.

“That’s right.” Carol had had enough of being

questioned. Noting the glance that passed between husband and wire,

she added, “The way Christmas is celebrated these days is just an

excuse for rampant commercialism. There’s no real spirit left in

the holiday anymore.”