Christmas Tales of Alabama (4 page)

Read Christmas Tales of Alabama Online

Authors: Kelly Kazek

Truman was a prodigious child who taught himself to read before he attended school and began writing at age eleven. Truman's busy mind, sensitivity and sense of abandonment would isolate him. Many years later, Truman told a reporter he felt like “a spiritual orphan, like a turtle on its back.”

He considered Sook his truest friend. With her childlike manner, she and Truman spent their days in innocent pursuits, such as killing flies in the house for a penny-each bounty, flying kites and searching for the perfect Christmas tree.

Their main activity each Christmas was baking fruitcakesâas many as thirtyâto give to people who caught their fancies or showed them kindness. One year, one of Sook's special fruitcakes was sent to President Roosevelt at the White House; another went to missionaries to Borneo. The year of “A Christmas Memory,” Truman, referred to in the story as “Buddy,” and Sook add another fruitcake recipient, Mr. Haha Jones, the bootlegger who sold them the whiskey to make the cakes. Truman's love of Sook and his childhood home shine through, making the story sparkle in the simplicity that overlays a hard truth: traditions, even comforting and happy ones, come to an end, leaving only memories in their wake.

Truman would become famous, though, not for short stories about the South but for books such as

Breakfast at Tiffany's

and the genre-bending

In Cold Blood

. Though Sook died when Truman was still a child living in New Orleans, many of his other cousins and aunts remained part of his life through adulthood. In later years, Truman would work on a book with Marie Rudisill, his mother's sister, whom he called Aunt Tiny, one of the orphans who had lived in the Faulks' Monroeville home. Rudisill and Truman had discussed writing a book of Sook's recipes, which Rudisill called “receipts,” but before it was completed, Truman became a world-renowned author caught in a busy social whirl. Then, in 1983, Rudisill wrote a book about Truman's childhood that angered him, along with many Monroeville residents.

Finally, Rudisill completed

Sook's Cookbook: Memories and Traditional Receipts from the Deep South

in 1991. Years after Truman's 1984 death, Marie used some of his recollections and Sook's recipes to publish

Fruitcake: Memories of Truman Capote and Sook

. While promoting the book, Marie made an appearance on

The Tonight Show

with Jay Leno, showing himâand guest Mel Gibsonâhow to make a fruitcake. The sassy attitude of the eighty-something Rudisill led to occasional repeat appearances on the show as the advice-dispensing “Fruitcake Lady.”

Rudisill died in 2006, days before the publication of her final book:

Ask the Fruitcake Lady: Everything You Would Already Know If You Had Any Sense

.

T

HE

S

TORY OF THE

“A

LABAMA

B

ABY

”

Just after Christmas 1897, Verna Pitts, a little girl who lived in Roanoke, Alabama, dropped and broke the prized porcelain bisque doll she had received as a gift. Little Verna, inconsolable, took her broken doll to Miss Ella, a lady known around town for her creativity and ingenuity.

Ella had a love of children, though she had none of her own, and took seriously the task of repairing Verna's doll. After pouring plaster into the broken head, she laid its pieces in the proper places and secured them with strips of cloth torn from Verna's petticoat. Miss Ella then coated the cloth with plaster of Paris and painted a new face on the doll. Little Verna took one look at her doll's new countenance and skipped happily away. This doll, Miss Ella was sure, would not break.

It was the start of a new career for the childless woman and a venture that would leave its legacy on the tiny town of Roanoke.

Ella Louise Gantt was born in April 1868 in Heard County, Georgia, to industrious, artistic parents. Her father fought with the Confederate army and was an inventor who held several patents, including one for a coiled spring used in mattresses. Ella's mother enjoyed painting. Unlike many young women of the time, Ella continued her education after high school and studied art at LaGrange College. Within a few years, she would arrive in Alabama to teach art at Roanoke Normal College. There she met Samuel Swainswright Smith, a local carpenter who went by the nickname “Bud.” They married two years later.

Bud built the couple a home on the picturesque town's Main Street. Now a housewife, Miss Ella spent time creating oil paintings and longing for children of her own. She was a well-known figure around Roanoke because she wore large hats and kept lots of animals, including a talking parrot. The parrot also had a reputation around town: it was known for singing hymns. Another legend states that when men would knock on the door asking if the Smiths needed a load of firewood, they would hear a response telling them to unload in the backyard. Eventually, Miss Ella went out back to find a yard filled with wood, and that was when she realized the parrot had apparently been ordering for her.

Ella's longing for children often took her to the local orphanage, particularly at Christmas, her favorite time of year. After repairing little Verna's doll, Miss Ella realized she could use the process to create dolls that would be virtually indestructible. Beginning in 1899, she began creating what would become known as the Alabama Indestructible Doll, or, more colloquially, the “Alabama Baby.”

Using her home as a factory, Ella created each doll by hand and then painted each of their faces. As the dolls' popularity grew, Bud constructed a two-story outbuilding as a factory, and Ella hired women to help with production of the dolls. Already accustomed to a house filled with animals, Miss Ella used carrier pigeons to send messages to conduct her business.

Dolls varied widely in appearance. They were typically from twelve to twenty-seven inches, although a few were as small as eight inches. The eyes were typically cornflower blue or deep brown. The lips were painted a deep orange. In some cases, hair was painted on; in others, real hair or sheep's wool was applied. Some dolls were custom made. Miss Ella would ask a child's parents to save locks from a haircut and use the future doll owner's hair to make the doll's wig. At the turn of the century, the dolls cost anywhere from seventy-five cents for an undressed, twelve-inch doll to twelve dollars for the largest doll with hair and a dress. A legend about the dolls' construction began in the early 1900s after a child reportedly dropped a doll in the street, where it was run over by truck. The doll, unscathed, earned the title Indestructible Doll. Ella also is known for making the first black dolls in the South.

At its peak, Miss Ella's factory produced eight thousand dolls in one year. Knowing his wife's love of the Christmas season, Bud built a wooden display sleigh that Miss Ella would place on the porch filled with dolls to distribute to local needy children. She also delivered numerous dolls to orphanages across Alabama. In 1904, Ella presented her dolls at the St. Louis Exposition. She won blue ribbons, and business boomed. The doll design was patented in 1905 but in Bud's name because women were not allowed to hold patents. The dolls' bodies were stamped “Mrs. S.S. Smith.”

At one point, Ella had twelve women working in the Main Street “factory.” Her dolls were sold in Sears & Roebuck catalogues and in Macy's stores. Within a few more years, Ella would finally have the family for which she longed. She was at the local train station in 1909 when she met a family with six children who were being delivered to the orphanage. Ella offered to take the six-week-old infant, who was quite ill. She unofficially adopted the child, Mary Louise Dixon, and changed her name to Macie Louise Smith. Later, she took in Cary Gantt, the son of her half brother, to rear.

The Alabama Indestructible Doll, or “Alabama Baby,” created by Ella Gantt Smith of Roanoke, was a favorite Christmas gift in the early 1900s.

Photograph courtesy of the Museum of East Alabama

.

In 1922, tragedy would bring Miss Ella's doll dynasty to a halt. Roanoke businessmen B.O. Driver and W.E. McIntosh wanted to become partners in the thriving business. They agreed the men would represent Miss Ella's company at the 1922 Toy Fair in New York. They took hundreds of orders for the dolls. On the way home, the train's last car, in which the men were traveling, was derailed and went into a creek near Atlanta. Driver and McIntosh died, and the orders were scattered to the winds.

Miss Ella and the people of the town mourned the loss of its citizens; however, the men's grieving families wanted moreâthey sued Miss Ella, accusing her of causing the men's deaths, and she eventually lost her factory.

In her last years, she lived in her Main Street home with her husband and animals and would walk aimlessly around town, cutting a mysterious figure in a long black cape with her beloved parrot on her shoulder. She died on April 22, 1932, and was buried in Roanoke. A local citizen raised funds to erect a marker inscribed: “Wife of S.S. Smith, Inventor, Manufacturer of the AL Indestructible Doll 1899â1932.”

Miss Ella, who loved children and giving gifts at Christmastime, would likely be surprised to know a museum now holds her dolls and tells of her life. The Randolph County Historical Museum on Roanoke's Main Street, near the Smiths' home, features a collection of the dolls, which are now highly collectible. In 1997, the U.S. Postal Service issued stamps bearing images of some of history's most beloved dolls, including Raggedy Ann and Miss Ella's Alabama Baby.

G

IRL

, G

OING

B

LIND

, T

HANKS

G

OVERNOR FOR

K

EEPING

F

AMILY

T

OGETHER

One morning in the fall of 1959, when Wyona Griffith was thirteen years old, she awoke to darkness.

“Mama, I can't see,” she said to her mother.

Imogene Griffith, thinking her daughter wanted to avoid going to school, dismissed the strange claim. Wyona, though, insisted: “I can't see anything.” Her mother suggested a trip to the doctor, and when Wyona readily agreed, Mrs. Griffith knew her daughter wasn't exaggerating. Something was wrong.

At the doctor's office, Wyona and her mother learned that the vision impairment stemmed from pressure in her brain, which had likely been growing since Wyona was kicked in the head by a calf at age four. Wyona's vision would later return, but the doctor in Kentucky, where the family was living at the time, said it would likely fade again. Wyona's mother and her father, James Griffith, decided to move the family to Attalla, Alabama, where Imogene's parents lived. Wyona, her parents and Wyona's little brother, who was three years old, made the move within weeks.

Back in Alabama, Wyona's father, a civil engineer, was unable to find work. He took a job in West Virginia and spent days at a time away from his family.

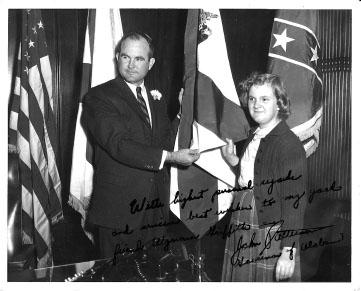

Wyona was “daddy's girl.” She missed her father terribly, especially during the time of uncertainty. She decided to write to the governor of Alabama, John Patterson, who seemed a kind man, and ask if he could find her father a job near home. With her mother doing the writing, Wyona related a message to the governor, who was moved by the family's plight. In a letter addressed to “Miss Wyona Jean Griffith,” Patterson wrote, “It is wonderful that you have written about your Daddy, and I will do everything I possibly can to assist him in finding employment.”