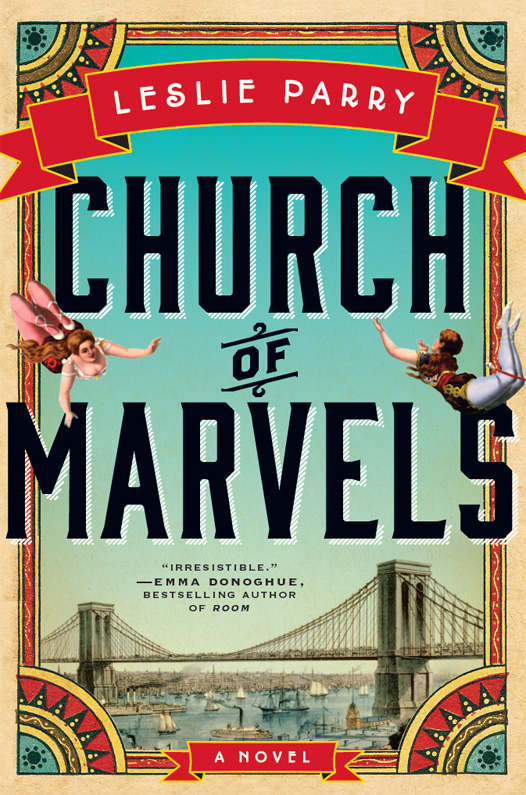

Church of Marvels: A Novel

Read Church of Marvels: A Novel Online

Authors: Leslie Parry

For my sister

In what distant deeps or skies

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

—“The Tyger,” William Blake

Claudia Ballard, you are the hero of this tale. Thank you for believing so ardently in this book, and for your wisdom, insight, patience, and humor. Thank you to the team at Ecco, especially Megan Lynch, Lee Boudreaux, and Dan Halpern. I couldn’t have asked for more incisive, clear-eyed, sensitive editors. Thanks to Elizabeth Sheinkman, Tracy Fisher, and the dedicated folks at WME; Jane Warren and Iris Tupholme at HarperCollins Canada; Lisa Highton and Federico Andornino at Two Roads. (And

grazie

, Federico, for helping me with the Italian phrases.) To everyone at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop—my teachers, my peers, the staff—profound thanks. This book would not exist without you.

This is a work of fiction, but I found inspiration in the writings of Nellie Bly, Herbert Asbury, and Earl Lind. I’m grateful to institutions like the New York Public Library, the New-York Historical Society, the Brooklyn Historical Society, and the Tenement Museum for further stoking my imagination. Thanks to Yaddo, the Vermont Studio Center, and the Kerouac Project—welcome shores on stormy seas.

Thank you to Adam Farabee, Melelani Satsuma, Zachary Mann, Sharon Smith, Dan Gomez, Jan Wesley, Virginia Parry, and Cris Capen for supporting this undertaking (and its roving author) at many vital turns. To my parents, Dai and Susie Parry, who were always ready with a word of encouragement, or a sing-along around the player piano. To my first reader, my sister Peanut: French martinis on me. To Florence Parry Heide and Suzanne Vidor Parry, who spent years listening to my stories, and regaling me with theirs: I wish you could hear this one. And to Joe Gerdeman, who was so certain for so many years: thank you for giving me a place to come home to.

I

HAVEN’T BEEN ABLE TO SPEAK SINCE I WAS SEVENTEEN YEARS

old. Some people believed that because of this I’d be able to keep a secret. They believed I could hear all manner of tales and confessions and repeat nothing. Perhaps they believe that if I cannot speak, I cannot listen or remember or even think for myself—that I am, in essence, invisible. That I will stay silent forever.

I’m afraid they are mistaken.

People who don’t know any better assume I’m a casualty of the stage life I was born into: a stunt gone awry beneath the sideshow’s gilded proscenium—mauled by a tiger, perhaps, or butchered by a sword that plunged so far down my throat I could kiss the hilt. But it’s a bit more complicated than that. No sword I’ve ever swallowed has been sharp enough to cut. At worst, those blades (blunted by pumice stones in my dressing room after hours) tickle like a piece of straw.

When I first came to Mrs. Bloodworth’s I knew nothing beyond the home I had left. I’d never been to the city before. I believed I had already seen the worst of the world, but of course I was wrong. I was just a scrappy tomboy from the seashore, my voice

a blend of Mother’s airy lilt and the peanut-cracking babel of the boardwalk. My mother was fearsome and beautiful, the impresario of the sideshow; she brought me and my sister up on sawdust, greasepaint, and applause. Her name—known throughout the music halls and traveling tent shows of America—was Friendship Willingbird Church. She was born to a clan of miners in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, but ran away from home when her older brother was killed at Antietam. She cut off her hair, joined the infantry, and saw her first battle at the age of fourteen. In the tent at night, she buried her face in the gunnysack pillow and wept bitterly thinking of him, hungry for revenge. A month later she was wounded. In the leaking hospital tent, a nurse cut open her uniform and discovered her secret. Before the surgeon could return, however, the nurse—not much older than Friendship herself—dug out the bullet, sewed up her thigh with a fiddle string, and sent her back to Punxsutawney in the dead of night.

But Friendship never made it home. Instead she traveled out to the great cities of the Middle West. She joined a troupe of actors and journeyed on to New York. She played town halls and hog fairs, bawdy houses, nickel parlors. She built her own theater at Coney Island—the Church of Marvels—and made a life for herself in a sideshow by the sea. It was the water she loved most, far away from the hills of Punxsutawney, from the black dust that fell like snow twelve months of the year. But she couldn’t shake the coal mines entirely: she prized industriousness and made us work.

All great shows, she told me when I was little (and still learning to flex the tiny muscles in my esophagus), depend on the most ordinary objects. We can be a weary, cynical lot—we grow old and see only what suits us, and what is marvelous can often pass us by. A kitchen knife. A bulb of glass. A human body. That something so common should be so surprising—why, we forget it. We take it

for granted. We assume that our sight is reliable, that our deeds are straightforward, that our words have one meaning. But life is uncommon and strange; it is full of intricacies and odd, confounding turns. So onstage we remind them just how extraordinary the ordinary can be. This, she said, is the tiger in the grass. It’s the wonder that hides in plain sight, the secret life that flourishes just beyond the screen. For you are not showing them a hoax or a trick, just a new way of seeing what’s already in front of them.

This,

she told me,

is your mark on the world. This is the story that you tell.

But I was young. I mistook my talent for worldliness, my vanity for a more profound sensibility. It was only when I arrived in Manhattan that I saw myself as coarse and strange, a Brooklyn savage with a bag of swords and ill-suited for any other life. I had come to seek the help of Mrs. Bloodworth, and in her care I tried to forget my old life, the troubles that had ended a naïve and happy childhood.

But the real troubles had yet to begin.

I would stand beside her in that smoky, sepulchral office, the curtains drawn against the hot glare of July. I wore a benign smile on my face while other young women, pale and nervous, sat before her desk. They cried into handkerchiefs, fiddled with abalone combs nested in their hair, drew fans to their faces when they felt sick or faint. Mrs. Bloodworth kicked her heels up on the desk and sighed out smoke. She nodded her head and closed her eyes in sympathetic meditation while the young girls sang of their sorrows. Before I lost my voice I sat there too, sick with the smell of blooming flowers, listening to my secrets echo off the mahogany walls.

Many think now that I’ve disappeared for good. They might even believe I have died. I can see them huddled in their grim houses, ruffle-breasted and thin-lipped, rattling dice over a backgammon board, kissing their pretty children good night. They believe they are safe. They believe that all is past and that I’ll hold my tongue.

Sometimes I want to laugh and say, “Oh but I have!” I’ve stared at it in my own cupped hands, stiff and bloody and fuzzed with white, gruesomely curled as if around a scream.

At seventeen I crossed the river alone. I didn’t know, when I departed, that in a few short months I would see the islands of New York—from Coney Island to Manhattan Island to the Island I shudder to name. Like the girls who came to Mrs. Bloodworth’s, I believed my decision was singular and private; I didn’t know that it would determine the fate of people I’d never met. The girls were frightened and alone, in need of a confessor. With a name such as mine, they believed me to be some sort of saint. But how could they know, as they trembled there at the desk, just how cruel the world could be, and I a willing part of it?

Let me say, this life is not the one I envisioned for myself. I remember the long-ago days when my mother would come up to me after a show, when I was tired and sweaty and sliding my swords into the rack. She’d pull me close and say, “My girl—how proud I am,” and I would hug her and smell the hair oil melting down her neck, her gabardine coat trailing the musk of the tiger cage. There are times when I long to feel just something of that old life—the crunch of sand beneath my feet, the beads of salt in my hair, the sight of Brighton Beach at dusk. I think of my sister, who is still there. I always believed we’d be together—the two of us living in our house by the sea, playing duets on the old piano, ringing in the new century as fireworks showered from the sky. (1900—how far away it seemed to me then! and now only a breath away.) And thinking of this, of her alone, of what I have never been able to tell her—this is something I cannot bear.

But this story, in truth, is not about me. I am only a small part of it. I could try to forget it, perhaps. I could try to put it behind me. But sometimes I dream that I’ll still return to the pageantry of the sideshow, hide myself beneath costumes and powder and paint, grow

willingly deaf amid the opiating roar of the audience and the bellow of the old brass band. It will be like the old days—when Mother was ferocious and alive, before the Church of Marvels burned to the sand. But how can I return now, having seen what I have seen? For I’ve found that here in this city, the lights burn ever brighter, but they cast the darkest shadows I know.