Circus Parade (15 page)

Authors: Jim Tully

Â

N

O man moved. The boss canvasman pushed the door shut quickly. Cameron and Finnerty, momentarily disturbed, resumed talking. The card players were soon quarreling again over the game.

“I took it with my ace,” insisted one.

“You did like hell, you mean you took an ace from underneath,” scowled the other.

Silver Moon Dugan joined Cameron and Finnerty.

Gorilla Haley rose, his jaws swollen with tobacco juice. He rushed to the door and swung it open.

“God Almighty, Gorilla, it's wet enough outside. Do you wanta flood the state?” the Ghost asked.

“Shut your trap,” flared Gorilla, shambling back to his place.

My worn brain would not allow me to sleep.

I thought once of crawling over the train to the horse car. One of the horses had been ill that day and I knew that Jock would travel with him. It suddenly dawned on me that the car had no end exits, out of which I might have muscled myself onto the roof of the next car.

Blackie, still holding his pipe, rose indifferently and walked to the end of the car. He stood still for a moment, legs spread apart, head down. In another second he laid his pipe on a wet piece of canvas, then turned, facing us.

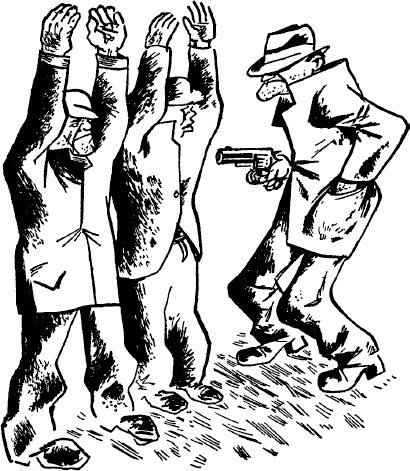

“Everybody stand up!” He whipped out the words sharply. In his extended right hand a blue steel gun. It looked to me as long as a railroad tie.

We all rose like soldiers standing at attention. Cameron was the most obedient. Silver Moon hesitated.

“Work fast, you lame bastard. I just want an excuse to send you to hell.” He took one step forward. “I'll put a hole through you so big you can pound a stake in it.” Silver Moon's lip curled, as he hesitated about putting up his hands.

For a paralyzing second I thought Blackie would shoot. He held the gun on a level with Dugan's heart and moved nearer. I closed my eyes as if to shut out the noise of the explosion. Then Blackie's voice went on. “What a dirty bunch of sons of bitches you all are.” Then, looking straight at Dugan, Cameron and Finnertyâ“Throw your gats down. And let me hear them fall hard. Come on.” Finnerty and Dugan threw revolvers on the floor.

“Now throw your money downâfastâevery God damn one of you.” Pocketbooks followed the guns. I threw a twenty-five cent piece.

Blackie half-grinned as it lit near a revolver.

He turned to me. “Open that door, kid.” Obedient at once, I slid the door backward its full length of six feet.

The noise of the rushing train increased. The rain swished across the car.

“Now everybody turn around. Walk to the doorâand

jump

. The guy that turns gets a bullet through his dome.”

Cameron looked at Blackie appealingly. Blackie laughed.

“You crooked old hypocrite, you can't talk your way outta this.” He lunged forward with the gun and shouted, “JUMP!”

Being second to no man in the art of catching a flying train, I jumped swiftly and with supreme confidence. The rest of the men followed me.

Before I could gain my balance on the soggy ground, a car had passed. There were two more to come. I knew every iron ladder and every portion of the train by heart. I could see the forms of the other men, some stretched out, others scrambling to their feet on the ground. I heard an unearthly screech. A gun went off.

My brain, long trained in hobo lore, functioned fast. I sized up the ground to make sure of my footing and looked ahead to make sure I would crash into no bridge while running swiftly with the train.

When one more car whirled by me, I started running.

If I missed the end of the last car I at least would not be thrown under the train. Running full speed, my brain racing with my feet, I knew that to grab was one thing, to grab and not to miss was another, and to cling like frozen death once my hands went round the iron rung of the ladder. I knew that I must race with the train, else if I grabbed it while I stood still, my arms might be jerked out of their sockets.

My cap was gone. The rain slashed across my face. When about to grab, my right foot slipped, and I was thrown off my balance for a second.

With muscles suddenly taut, then loosened like a springing tiger's, I sprang upward. My hands clung to the iron rung. My body was jerked toward the train. Thinking quickly, I buried my jaw in my left shoulder, pugilist fashion. It saved me from being knocked out by the impact of my jaw with the side of the car. I finally got my left foot on the bottom of the ladder, my right leg dangling.

The car passed the group who had been redlighted with me. A man grabbed at my right foot. I kicked desperately, and felt for an instant my foot against the flesh of his face. My arms ached as though they were being severed from my shoulders with a razor blade. A numbness crept over me. My brain throbbed in unison with my heart. Drilled in primitive endurance of the road for four long years, I was to face the supreme test.

I had no love for the red-lighted men. Rather, I admired Blackie more. Neither did I blame him for red-lighting me. A man had once trusted another in my world. He was betrayed.

I had the young road kid's terrible aversion against walking the track for any man. My law wasâto stay with the train, to allow no man to “ditch” me.

When the numbness left me I crawled up the ladder. Blinded by the rain, my hair plastered to my head in spite of the wind that roared round the train, I lay, face downward, and clawed with tired hands at the roof of the smooth wet car.

Sometime afterward, whether a minute or an hour, I do not know, I tried to rise. My arms bent. I lay flat again.

My mania had been to tell Jock. It suddenly dawned on me to tell anybody I saw. But how could I see anyone while the train lurched through the wind-driven and rain-washed night?

I cried in the intensity of emotion. Pulling myself together, I dragged my body to the end of the first car, about sixty feet. Reaching there, I had not the strength to muscle my body to the next car. After a seemingly endless exertion I pulled myself across the three-foot chasm between the two cars. Beneath me the wheels clicked with fierce revolutions on the rails. The wind blew the rain in heavy gusts through the chasm.

With the aid of the chain which ran from the wheel at the top of the car to the brake beneath, I worked my body around to the ladder, and crawled laboriously to the top of the second car. My muscles throbbed with pain at the armpits. I wondered if I had dislocated my arms. I tried to crawl on my hands and knees, and gave it up. Finally I succeeded in dragging myself across the second car. My heart pounded as though it would jump from my breast.

I leaned out from my position between the cars. The light still gleamed in the open door of the car from which we had been red-lighted.

Blackie was standing in the doorway. His shadow was thrown far across the ground. The running train gave it a weird dancing effect. It pumped over the rough earth and cut through telegraph poles and fences as the rain splashed upon it.

The engine whistled loud and long. My heart jumped with glee. It was going to stop. Suddenly the train gained momentum and the engine whistled twice. This meant: straight through. We passed a few red and green lights, and later some that were yellowish white.

The whistle shrieked again, a low moaning dismal effort like a whistle being blown under water. I sensed a long run for the train. The fireman's hand lay heavily on the bell rope. It became light as day each time he opened the fire-box to shovel in coal.

The rain still slashed downward with blinding fury. In spite of everything my eyes became heavy. Knowing the folly of going to sleep and falling between the cars, I opened my coat and held my body close to the iron rod which held the brake. I then buttoned the coat around it. While being forced to stand as rigid as one in a straight jacket, it would nevertheless save me from being dashed under the wheels.

After many wet miles the train slowed at the edge of a railroad yard. Lights from engines blended with white steam and made the yards light as early day.

I looked across the yards and saw Blackie making for the open road.

We gained speed for a few minutes and then ran slower, at last coming to a stop in the yards.

I hurried to the horse car and found Jock. He was sitting on some straw near Jerry, the sick horse. I gasped out the story of the red-lighting to him.

Jock said without energy, “It was a tough break for you, kid,” and shrugged his shoulders. “I'll tell the Baby Buzzard.” He frowned. “We'll have to go back after them, I guess.”

He studied for another moment. “It would be a great stunt to let 'em walk in. They deserve it.

But no

. I guess it's best for you to come and tell the Baby Buzzard. We'll be all finished in a week and you'd lose your wages if you ducked now and didn't tell.”

“Yeah, Jock, you're right,” I said. And then, “I saw Blackie beatin' it across the yards about a mile back.”

“Well,” exclaimed Jock, “say nothin' about it, kid. A guy that kin pull a stunt like that deserves to go free. I don't think he meant you no harm. He

had

to red-light you, too.”

“Gosh! I wonder what he'd think if he knew I made the train again.”

“He wouldn't be surprised. He'd have made it if you'd of red-lighted him. He's just a hell of a guy, that's all.”

Jock put on his soft grease-stained hat. “We'd better go an' tell the Baby Buzzard together, kid, but don't mention seein' Blackie. Let him make his getaway. I wouldn't turn a dog over to the law.”

“All right, Jock,” I muttered, and followed him out of the car.

Â

T

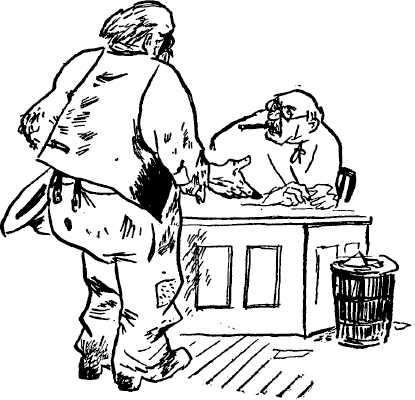

HE misty morning at last turned clear. The sun shone bright. We walked toward the Baby Buzzard's car. In a few words I told my story. The Baby Buzzard's eyes narrowed.

“Who'd you say red-lighted 'em?”

I told her again.

“What become of him?” she asked.

“That don't matter,” answered Jock, “it's what'll become of them if we don't get 'em. Maybe they're hurt, or even killed.”

The Baby Buzzard sneered. “Killed hell. No sich luck for some of 'em.” Then quickly, “Come with me.”

We followed her toward the engine. The fireman leaned out of the left window and watched the engineer oil the large drive wheels.

The Baby Buzzard approached him and asked, “Are you a runnin' this here train?”

“I was, till it stopped,” he answered with irritation.

The engineer's answer angered the Baby Buzzard.

“Well, would you mind runnin' your damn train back about fifty mile an' pickin' up my husban' and some more of his men that got red-lighted with the kid here.”

“Not me, lady. I'm all through. I've been smellin' this circus long enough. You'll have to tell your troubles to the trainmaster. He's right over in that corner of the round house.”

We walked across the tracks in the direction of the round house, a place in which the engines were kept like so many automobiles in a huge round garage. The Baby Buzzard hobbled along with us, delivering a scathing remark toward the engineer, which ran, “The nerve o' that devil. No wonder poor people git no wheres in this world. They're too damn saucy.”

The trainmaster had one arm and a happy smile. His hair was sandy, his face the color of an overripe mulberry. He telephoned the chief train despatcher and asked, “What's due out of âââ? Boss of the circus and some other fellows made to walk the plank.”

Turning to meâ“You say it was about fifty miles out? No towns between of any size?”

“No sir.”

The despatcher made answer!

“Then Number Four'll ketch 'em if they've stayed close to the track. All rightâtell conductor Number Four to be on lookout for themâbring 'em on in here.”

“How long'll it be?”

“About three or four hours, lady.”

The Baby Buzzard grunted and walked away. “Pay the railroads all the damn money you make an' then they can't do you a little favor. Have to wait all this time to git started.”

The Baby Buzzard lost no time in getting the circus unloaded. The property boss was given Silver Moon Dugan's work to do. Buddy Conroy took charge in place of Slug Finnerty.

She hobbled about snapping orders. The men cursed her under their breath.

An old “roughneck” canvasman and stake-driver laid out the tent on the lot. And to the surprise of all it was done as well as Dugan could have accomplished.

Jock gave me some dry clothes and allowed me to sleep until time for the parade to return. All that day I basked in my little glory.

Number Four arrived after dinner with its diversified cargo.

Cameron with both legs broken, was carried out of the caboose. On his face was scorn for his position and pity for himself.

The entire circus gathered about the train. Silver Moon Dugan looked ashamed. His limp was more decided.

“How's hittin' the ties, Silver?” yelled a voice.

“Go to hell,” was Silver's retort.

The Ghost and Gorilla Halen were unhurt.

Back of them came the young fellow whom Silver Moon Dugan had red-lighted.

His clothing was badly torn, his face deeply scratched.

As I had spread the story of his first having been red-lighted by Dugan, his appearance was greeted with a wild shout.

A doctor was called. He pulled and twisted at Cameron's legs, and then put them in crude plaster casts. The battered barbarian looked at them when the doctor had finished. He glanced then at the Baby Buzzard and shook his head violently, at last snapping out:

“God damn the God damned luck!”

One of the hardest, the most merciless, and the meanest of mankind, who had red-lighted many men himself and who had cheated many hundreds in his wandering life, he added:

“That man ain't human. He's lower'n a skunk's belly.”

“Well he's hard enough to be human,” sneered Silver Moon Dugan, “and I've seen him somewhere. It seems to me he pulled a fast one with Robinson's five or six years ago. Believe me or not, if I ever put my glims on 'im agin there'll be music along this railroad. I'll play âHome Sweet Home' on his God damn ribs with bullets.”

Cameron tried to turn over. His body twitched with pain.

“You're a tune too late, Silver. You'll never see that bozo this side of hell.” His eyes were bleared with the wind and rain of the night. They were crossed for a moment with clouds of humor.

“But you gotta say this, Silver, you done met your match in that greaser.”

“I have like so much hell,” returned Silver Moon Dugan.

Cameron, oblivious of the retort, added:

“It's funny about people. The minute I saw that guy I felt like apologizin' for ownin' the show. That's the kind of a guy he was. His damn hard eyes were like diamond drills an' his nose hooked like a buzzard's. He's no regular roughneck, I knew it, but what'n hell is he?”

The Baby Buzzard, never soft, looked down at the hulk with broken legs. She started to say something, changed her mind, then turned to me. Her flat and aged breast rose once, then sank. An emotion was killed within her.

In all the months she displayed no interest in me, save that I could read well aloudâand now:

“Where you from, kid?”

“Oh, I'm just a drifter. Joined on in Louisiana before the Lion Tamer got bumped off.”

“That's right. I'd forgot,” she returned. “Did that lousy wretch take your money too?”

“My last two bits,” I replied.

The Baby Buzzard allowed herself the shadow of a grin. Then for fear of being too generous with herself, she frowned.

“Damn his hide, the nerve. A guy that'd do that ud skin a louse for its hide.”

She handed me a half dollar. Clutching it in my hand I returned to Jock.

Cameron insisted on being present each time the tent was pitched. A covered wagon was turned over to him, the canvas on each side being made to roll up like curtains. It was roped off from the gaze of the public. Here he would lie like a flabby, wounded but unbeaten general directing his forces. I was his errand boy.

The circus was to close in a week. The nights even in the South were now cold. Frost covered everything each morning. Roughnecks, musicians, acrobats, all talked of a headquarters for the winter.

Cameron's reputation as a red-lighter had been accentuated by his own catastrophe. “He'll have to pay us now, the old devil. He can't make a gitaway on broken pins,” was the comment of the old roughneck who had laid out the tents in Silver Moon Dugan's absence.

But nevertheless we were all worried about our wages. If we allowed the show to go into headquarters in another state it would be impossible to collect. We would not be allowed to go near Cameron's headquarters. Citizens and police would protect Cameron against the claims of circus hoboes. Such communities had always protected Cameron and his tribe of red-lighting circus owners from the ravages of roughnecks who wanted justice.

I could feel the tension on the lot. Many of the older canvasmen had what is known as a “month's holdback” due them, twenty or thirty dollars for a month of drudging labor. It was wealth to men of our kind to whom a dollar was often opulence.

The final pay-day would cost Cameron several thousand dollars. How would he face the situation with two broken legs? We all wondered.

“You'll git yours, kid, don't worry,” Jock had assured me. But even then, I was not so sure.

To ease my mind I talked over the matter indirectly with the Baby Buzzard.

“Gosh, I'll feel rich next Thursday, when the show closes,” I said to her.

“What for?” she asked. “Money only runes people like you. You won't do nothin' with it but git drunk an' go to whore houses an' git your backbones weak.”

I passed the word along. It made us more determined to collect than ever.