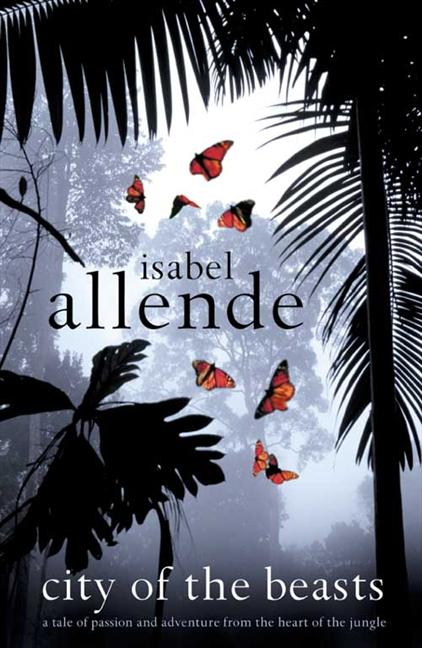

City of the Beasts

ALSO BY ISABEL ALLENDE

The House of the Spirits

Of Love and Shadows

Eva Luna

The Stories of Eva Luna

The Infinite Plan

Paula

Aphrodite: A Memoir of the Senses

Daughter of Fortune

Portrait in Sepia

City of the Beasts

Translated from the Spanish by

Margaret Sayers Peden

HARPERCOLLINS

PUBLISHERS

City of the Beasts

Copyright © 2002 by Isabel Allende

English translation copyright © 2002

by HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

Printed in the U.S.A. All rights reserved.

www.harpercollins.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Allende, Isabel.

City of the beasts / by Isabel Allende; translated from the Spanish by Margaret Sayers Peden. p. cm.

Summary: When fifteen-year-old Alexander Cold accompanies his individualistic grandmother on an expedition to find a beast in the Amazon, he experiences ancient wonders and a supernatural world as he tries to avert disaster for the Indians.

ISBN 0-06-050918-X—ISBN 0-06-050917-1 (lib. bdg.)—ISBN 0-06-051195-8 (large print : pbk.)

[1. Adventure and adventurers—Fiction. 2. Supernatural—Fiction. 3. Amazon River Valley—Fiction. 4. Indians of South America—Amazon River Valley—Fiction. 5. Grandmothers—Fiction.] I. Peden, Margaret Sayers. II. Title.

PZ7.A43912 Ci 2002 2002022338

[Fic]—dc21 CIP

AC

Typography by Hilary Zarycky

123456789 10

First Edition

To Alejandro, Andrea, and Nicole,

who asked me for this story

Chapter One

The Nightmare

Chapter Two

The Eccentric Grandmother

Chapter Three

The Abominable Jungleman

Chapter Four

The Amazon River

Chapter Five

The Shaman

Chapter Six

The Plot

Chapter Seven

The Black Jaguar

Chapter Eight

The Expedition

Chapter Nine

People of the Mist

Chapter Ten

Kidnapped

Chapter Eleven

The Invisible Village

Chapter Twelve

Rites of Passage

Chapter Thirteen

The Sacred Mountain

Chapter Fourteen

The Beasts

Chapter Fifteen

The Crystal Eggs

Chapter Sixteen

The Water of Health

Chapter Seventeen

The Cannibal-Bird

Chapter Eighteen

Bloodstains

Chapter Nineteen

Protection

Chapter Twenty

Separate Ways

The Nightmare

ALEXANDER COLD AWAKENED at dawn, startled by a nightmare. He had been dreaming that an enormous black bird had crashed against the window with a clatter of shattered glass, flown into the house, and carried off his mother. In the dream, he watched helplessly as the gigantic vulture clasped Lisa Cold's clothing in its yellow claws, flew out the same broken window, and disappeared into a sky heavy with dark clouds. What had awakened him was the noise from the storm: wind lashing the trees, rain on the rooftop, and thunder.

He turned on the light with the sensation of being adrift in a boat, and pushed closer to the bulk of the large dog sleeping beside him. He pictured the roaring Pacific Ocean a few blocks from his house, spilling in furious waves against the cliffs. He lay listening to the storm and thinking about the black bird and about his mother, waiting for the pounding in his chest to die down. He was still tangled in the images of his bad dream.

Alexander looked at the clock: six-thirty, time to get up. Outside, it was beginning to get light. He decided that this was going to be a terrible day, one of those days when it's best to stay in bed because everything is going to turn out bad. There had been a lot of days like that since his mother got sick; sometimes the air in the house felt heavy, like being at the bottom of the sea. On those days, the only relief was to escape, to run along the beach with Poncho until he was out of breath. But it had been raining and raining for more than a week—a real deluge—and on top of that, Poncho had been bitten by a deer and didn't want to move. Alex was convinced that he had the dumbest dog in history, the only eighty-pound Labrador ever bitten by a deer. In the four years of his life, Poncho had been attacked by raccoons, the neighbor's cat, and now a deer—not counting the times he had been sprayed by the skunks and they'd had to bathe him in tomato juice to get rid of the smell. Alex got out of bed without disturbing Poncho and got dressed, shivering; the heat came on at six, but it hadn't yet warmed his room, the one at the end of the hall.

At breakfast Alex was not in the mood to applaud his father's efforts at making pancakes. John Cold was not exactly a good cook; the only thing he knew how to do was pancakes, and they always turned out like rubber-tire tortillas. His children didn't want to hurt his feelings, so they pretended to eat them, but anytime he wasn't looking, they spit them out into the garbage pail. They had tried in vain to train Poncho to eat them: the dog was stupid, but not that stupid.

"When's Momma going to get better?" Nicole asked, trying to spear a rubbery pancake with her fork.

"Shut up, Nicole!" Alex replied, tired of hearing his younger sister ask the same question several times a week.

"Momma's going to die," Andrea added.

"Liar! She's not going to die!" shrieked Nicole.

"You two are just kids. You don't know what you're talking about!" Alex exclaimed.

"Here, girls. Quiet now. Momma is going to get better," John interrupted, without much conviction.

Alex was angry with his father, his sisters, Poncho, life in general—even with his mother for getting sick. He rushed out of the kitchen, ready to leave without breakfast, but he tripped over the dog in the hallway and sprawled flat.

"Get out of my way, you stupid dog!" he yelled, and Poncho, delighted, gave him a loud slobbery kiss that left Alex's glasses spattered with saliva.

Yes, it was definitely one of those really bad days. Minutes later, his father discovered he had a flat tire on the van, and Alex had to help change it. They lost precious minutes and the three children were late getting to class. In the haste of leaving, Alex forgot his math homework. That did nothing to help his relationship with his teacher, whom Alex considered to be a pathetic little worm whose goal was to make his life miserable. As the last straw, he had also left his flute, and that afternoon he had orchestra practice; he was the soloist and couldn't miss the rehearsal.

The flute was the reason Alex had to leave during lunch to go back to the house. The storm had blown over but the sea was still rough and he couldn't take the short way along the beach road because the waves were crashing over the lip of the cliff and flooding the street. He took the long way, running, because he had only forty minutes.

For the last few weeks, ever since his mother got sick, a woman had come to clean, but that morning she had called to say that because of the storm she wouldn't be there. It didn't matter, she wasn't much help and the house was always dirty anyway. Even from outside, you could see the signs; it was as if the whole place was sad. The air of neglect began with the garden and spread through every room of the house, to the farthest corners.

Alex could feel his family coming apart. His sister Andrea, who had always been different from the other girls, was now more Andrea than ever; she was always dressing in costumes, and she wandered lost for hours in her fantasy world, where she imagined witches lurking in the mirrors and aliens swimming in her soup. She was too old for that. At twelve, Alex thought, she should be interested in boys, or piercing her ears. As for Nicole, the youngest in the family, she was collecting a zoo full of animals, as if she wanted to make up for the attention her mother couldn't give her. She was feeding several of the raccoons and skunks that roamed outside the house; she had adopted six orphaned kittens and was keeping them hidden in the garage; she had saved the life of a large bird with a broken wing; and she had a three-foot snake in a box in her room. If her mother found that snake, she would drop dead on the spot, although that wasn't likely, because when she wasn't in the hospital, Lisa spent the day in bed.

Except for their father's pancakes and an occasional tuna-and-mayonnaise sandwich, Andrea's specialty, no one in the family had cooked for months. There was nothing in the refrigerator but orange juice, milk, and ice cream; at night they ordered in pizza or Chinese food. At first it was almost like a party, because each of them ate whenever and whatever they pleased, mainly sweets, but by now everyone missed the balanced diet of normal times.

Alex had realized during those months how enormous their mother's presence had been and how painful her absence was now. He missed her easy laughter and her affection, even her discipline. She was stricter than his father, and sharper. It was impossible to fool her; she had a third eye and could see the unseeable. They didn't hear her singing in Italian now; he missed her music, her flowers, the once-familiar fragrance of fresh-baked cookies, and the smell of paint. It used to be that his mother could work several hours in her studio, keep the house immaculate, and still welcome her children after school with cookies. Now she barely got out of bed to walk through the rooms with a confused air, as if she didn't recognize anything; she was too thin, and her sunken eyes were circled with shadows. Her canvases, which once were explosions of color, sat forgotten on their easels, and her oils dried in their tubes. Lisa seemed to have shrunk; she was little more than a silent ghost.

Now Alex didn't have anyone to scratch his back, or brighten his spirits when he got up feeling depressed. His father wasn't one for spoiling children. Besides, John had changed, like everyone else in the family. He wasn't the calm person he once had been. He was often cross, not only with his children but with his wife, too. Sometimes he shouted at Lisa because she wasn't eating enough or taking her medicine, but immediately he would feel terrible about his outburst and ask her to forgive him. Those scenes left Alex trembling; he couldn't bear to see his mother so weak and his father with tears in his eyes.

When Alex got home that noontime, he was surprised to see his father's van; at this hour he was usually at the clinic. He went in through the kitchen door, which was always unlocked, intending to get something to eat, pick up his flute, and shoot back to school. He looked around, but all he found were the fossilized remains of last night's pizza. Resigned to going hungry, he went to the refrigerator to get a glass of milk. That was when he heard the crying. At first he thought it was Nicole's kittens in the garage, but then he realized that the sound was coming from his parents' bedroom. Not meaning to spy, almost without thinking, he walked down the hall to their room and gently pushed the partly opened door. He was petrified by what he saw.

In the center of the room was his mother, barefoot and in her nightgown, sitting on a small stool with her face in her hands, crying. His father, standing behind her, was holding an old straight razor that had belonged to Alex's grandfather. Long clumps of black hair littered the floor and clung to his mother's fragile shoulders, and her naked skull gleamed like marble in the pale light filtering through the window.

For a few seconds, Alex stood frozen, stupefied, not taking in what he saw: the hair on the floor, the shaved head, the knife in his father's hand only inches from his mother's neck. When he came to his senses, a terrible cry rose up from his very toes and a wave of madness washed over him. He threw himself on John, pushing him to the floor. The razor traced an arc through the air, brushed past Alex's forehead, and landed point first in the floorboards. His mother began to call Alex's name, tugging at his clothing to pull him away as he blindly pounded on his father, not seeing where the blows landed.

"It's all right, son! Calm down, it's nothing," Lisa begged, weakly trying to hold Alex as his father protected his head with his arms.