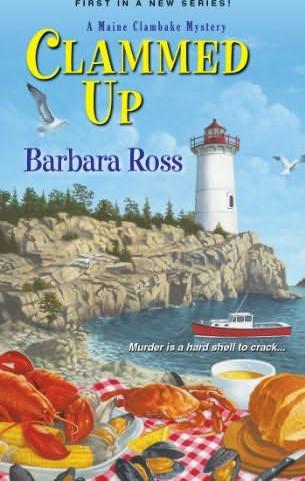

Clammed Up

MURDER IN MAINE

“Is there any way Ray Wilson could have done this to himself ?” I asked.

“Doesn’t look like it,” Lieutenant Binder answered.

I cleared my throat and asked the question I’d been dreading. “How long will we be closed?” I felt selfish asking. A man was dead. But the future of our business depended on the answer.

“Certainly you’ll be closed tomorrow. After that, it’ll be day-to-day.”

The Snowden Family Clambake was teetering on the brink as it was. Every day we were shut would bring us closer to financial ruin. And to losing this island. Which I was convinced would break my mother, still recovering from my father’s death. That’s why I’d come home. To save the business that provided for my family. And to save Morrow Island for my mother.

“Lieutenant, we have a short season here on the coast. Every day we’re shut—”

“I understand, Ms. Snowden. I do. But we need to process the scene. We also need to make sure the island is a safe place for you and your guests.”

A safe place?

“You think this could have something to do with the island?”

“You think this could have something to do with the island?”

It was another question I hadn’t wanted to ask, though it was all I had thought about for a couple of hours . . .

CLAMMED UP

Barbara Ross

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

MURDER IN MAINE

Title Page

MURDER IN MAINE

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Recipes

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

Copyright Page

This book is dedicated to Bill Carito,

my best friend, the love of my life,

who has supported me in everything I’ve ever done.

Honey, I’m sorry I got annoyed at you for breathing

while I was trying to write.

my best friend, the love of my life,

who has supported me in everything I’ve ever done.

Honey, I’m sorry I got annoyed at you for breathing

while I was trying to write.

Chapter 1

She hadn’t seemed like a Bridezilla. Not in the least. Most brides who would celebrate their wedding with a clambake on an island in Maine were pretty relaxed. Just think about all that broth and butter, and the dress-staining properties of blueberry grunt. We were making the first run of the day out to Morrow Island with the wedding party, well almost all of the wedding party, and the bride had a grip on my upper arm like a blood pressure cuff that tightened with each swell our boat steamed over.

“Julia. Turn. The Boat. Around,” the bride, a willowy brunette named Michaela, demanded.

I shook my head. “Not a good idea. We’ve discussed this. We’ll get to the island and unload the food. Then the boat will head right back to the harbor.”

My eyes swept the deck, searching for the maid of honor. Wasn’t calming the bride her job? But she was off in a corner of the stern with the bridesmaids, gossiping vigorously. I knew exactly what they were talking about. The best man wasn’t onboard. Neither was the groom.

Back at the dock, when the best man hadn’t shown up at the appointed time, there’d been some nervous joking. The night before, after the rehearsal dinner, a group had gone out to Crowley’s, the noisiest tourist bar in Busman’s Harbor, and evidently, the best man had gotten pretty hammered. Nobody remembered walking him to his hotel. He must have been the last member of the wedding party left in the bar.

As time had ticked by, his continued absence wasn’t so funny. His hotel door had been pounded on. His cell phone had been tried, though service was pretty spotty in the harbor. I called from my phone, which would at least get a signal, but his end went straight to voice mail.

“We have to get going,” I’d finally told Michaela. “If we don’t get the food over to the island soon, you’ll have a lot of hungry guests.” The hold of the

Jacquie II

was filled with live lobsters, clams, and sweet corn that still needed to be shucked so only one thin layer of husk remained.

Jacquie II

was filled with live lobsters, clams, and sweet corn that still needed to be shucked so only one thin layer of husk remained.

Michaela had agreed. “Julia’s right. Ray can take the later boat with the guests.”

The groom, Tony, who up to then had been relaxed and smiling, shook his head. “You guys go along. Get to the island, get settled, fix your hair, or whatever it is you’ve gotta do. I’ll find Ray and bring him on the later boat.”

“But—” Michaela had started to protest, but then the reality of the situation hit her.

The other groomsmen were her teenage brothers. Tony’s father was slightly disabled by a stroke and Michaela’s dad had died years before. The ancient minister wasn’t up to searching the harbor. Michaela’s mother, Tony’s mother, and the bridesmaids were already dressed and in high heels. The rest of the passengers included the DJ and my crew, the cooks, waitstaff, and general helpers who made the clambake run smoothly. As far as I knew, none of my folks had ever seen the best man. There was really no one but the groom who could look for him.

“Don’t worry.” Tony kissed Michaela on the forehead. “I’ll be there. Ray and I will both be there.” And then he’d walked down the gangway and off the dock.

At the time, I’d thought Michaela took it pretty well, but now she had a wild look in her eyes and seemed perilously close to a meltdown. To anyone watching, we must have looked like quite a pair. We were the same age, thirty, but Michaela was tall, exotic-looking, and already dressed in her beautiful gown. I was blond, small and wiry, and wore my new uniform of faded jeans, work boots, and a sweatshirt. I’d thought about dressing differently in honor of the occasion, but putting on a clambake was hard, physical work. Thank goodness I’d kept up my gym membership for the nine years I’d lived in Manhattan.

I’d known Michaela vaguely, years ago, as a friend of a friend in New York City, but we’d never been close and I didn’t know what to say to her now.

From across the deck, my brother-in-law Sonny made a face at me that simultaneously said

Now look what you’ve got us into

and

I told you so.

I rolled my eyes at him.

Now look what you’ve got us into

and

I told you so.

I rolled my eyes at him.

Back in early spring when I’d explained my idea to “expand” the Snowden Family Clambake business—I’d deliberately avoided the inflammatory word

save

—by adding private parties, company picnics, weddings and the like, Sonny was dead set against it. And when I told him private catering would require an expanded menu, he’d lost it.

save

—by adding private parties, company picnics, weddings and the like, Sonny was dead set against it. And when I told him private catering would require an expanded menu, he’d lost it.

“The bake is the bake!” he’d yelled. “Twice a day we haul two hundred tourists out to the island, feed them steamers, lobsters, corn, potatoes, an onion, and a hard-boiled egg, all of which we cook in a hole in the ground, the same way the Indians taught our Puritan forefathers. The Maine clambake is sacred. Don’t mess with the bake!”

“Sonny, Indians didn’t start the bake. My father did. In 1979. And since the economic crisis, there aren’t two hundred tourists on that boat twice a day. Sometimes there are fewer than two dozen. In Maine, we’ve got exactly four months to make our money. Four months. So if you think I’m going to stand by and lose my father’s business because you can’t be flexible, you’re wrong!”

We’d retreated to our separate corners, knowing we’d be going a few more rounds. Sonny was more right about some of it than I was. My father had started the Snowden Family Clambake Company, but he certainly didn’t invent the clambake. As to the Native Americans, we knew they ate a lot of shellfish, as shown by the giant, prehistoric piles of oyster shells called middens just up the road in the Damariscotta River. And we knew the Puritans ate lots of clams, or even more would have died during those early winters. But the rest was as much mystery as history. One thing I was sure of. The Indians didn’t teach Sonny’s Puritan forbearers how to do a clambake. If his ancestors were anything like him, no one could teach them a damn thing.

Just as Morrow Island came into view, the maid of honor, whose name was Lynn, finally woke up to her duty. She gently pried the bride off my arm and walked her to a seat. “Ray is just a jerk,” I heard Lynn say, but Michaela shook her head no.

I rubbed my arm to restore the feeling to my tingling fingers, moved to the bow, picked up the cable, and got ready to land.

Morrow Island. I still couldn’t believe Sonny had almost lost it. The island had been in my mother’s family for a hundred and thirty years. It was a great piece of rock, really. Thirteen acres, with good deep-water dockage, and that rarity in Maine, a small sandy beach. On a high hill at the center of the island stood Windsholme, the summer “cottage” built by my great-great-grandfather at the height of the Gilded Age.

As our captain maneuvered the

Jacquie II

into dock, the island’s caretakers, Etienne and Gabrielle, hurried to meet us. The mansion was abandoned during World War II, when no one had servants to run the place or fuel to get there. The family money was long gone by then, anyway. After the war, my grandfather built a modest house by the dock. That’s where my mother had spent her summers, and where she’d fallen in love with the boy from town who delivered groceries in his skiff.

Jacquie II

into dock, the island’s caretakers, Etienne and Gabrielle, hurried to meet us. The mansion was abandoned during World War II, when no one had servants to run the place or fuel to get there. The family money was long gone by then, anyway. After the war, my grandfather built a modest house by the dock. That’s where my mother had spent her summers, and where she’d fallen in love with the boy from town who delivered groceries in his skiff.

Now Etienne and Gabrielle lived in the little house all summer. Etienne was our bake master, managing the fire pit where the clambake was cooked. Gabrielle ran the kitchen and made the deep-dish blueberry grunt we served to guests at the end of the meal.

I jumped onto the dock. A steady breeze blew from the south and I wished the temperature were a couple degrees warmer for Michaela’s big day. In spite of what the Busman’s Harbor Tourism Board would have you believe, mid-June was still pretty early for coastal Maine. I closed my eyes for just a second and breathed in deep. Etienne had already started the towering hardwood fire that heated the stones to cook the meal. The smell of burning oak, sea air, and a slight tang from the scrub pines clinging to the rocks was Morrow Island to me. No matter where I went or what I did, it would always mean home.

Etienne and Sonny helped the rest of wedding party onto the dock and we started the long trudge up the great lawn toward Windsholme. Constructed in stone, in deference to the sea winds, the mansion had twenty-seven rooms, not counting bathrooms, storerooms, and pantries. Inside, it was gracious and unexpectedly airy. The double front doors opened into a three-story grand foyer with a staircase that rose, turning back on itself, all the way to the top floor.

We didn’t use Windsholme for the clambakes, though we allowed guests to relax in the rockers lining its deep front porch. Sadly, the inside wasn’t in great condition and we didn’t want customers getting hurt or lost. But to host weddings I knew there had to be a place for people to dress or fix their hair and makeup. The mansion’s 1920s-era knob and tube wiring had long been turned off. In a fit of optimism, I’d hired electricians to rewire a couple rooms on the main floor to handle modern hair dryers and makeup lights.

As we walked up the lawn, the discussion going on behind me was about the best man, Ray Wilson. He was selfish, irresponsible and immature, the maid of honor insisted. “He had one job to do for this wedding. Show up and bring the rings. And he couldn’t get that right.”

“Ray’s changed,” Michaela responded. “Really, he has. I’m worried about him. Something’s wrong.”

“I’m sure he’ll be here.” I tried to sound confident.

And he was. When I threw open Windsholme’s great front double doors, Ray Wilson hung by a rope around his neck from the grand staircase. Dead.

Other books

Vita Brevis by Ruth Downie

Can You Say Catastrophe? by Laurie Friedman

JAKrentz - Witchcraft by User

A Missing Peace by Beth Fred

A Killer in Winter by Susanna Gregory

Until I Break by M. Leighton

Out of Her League by Lori Handeland

Forever Yours (#3) by Longford , Deila

Rules for 50/50 Chances by Kate McGovern

Realm of the Goddess by Sabina Khan