Clash of Kings (22 page)

Authors: M. K. Hume

Ignorant of their captive’s thrall in the light of the moon, the Saxons pressed on, maintaining a steady pace to spare their horses from becoming overly distressed. When they paused in the early hours of the morning to rest their mounts for an hour or two, Myrddion was almost asleep and his legs and hands were numb from disuse. When he was lifted off Horsa’s stallion, the Saxon captain was gentle as he laid him on a soft swathe of heavy grass that had dried in the colder weather of late autumn. Hengist draped his own woollen cloak over the boy, remembering his own sons, far away in a sturdy hut on the island of Thanet.

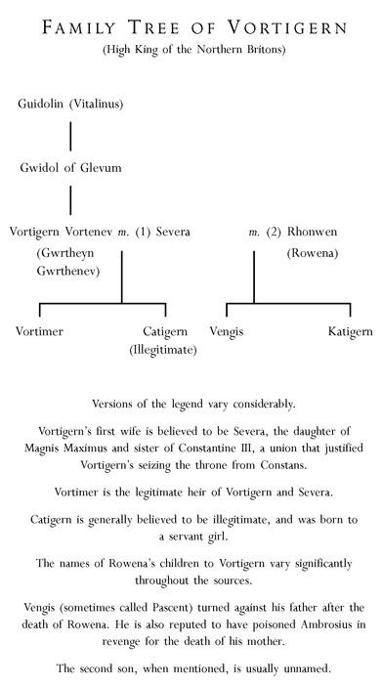

A small kindness, but a nothing, really, in the fate of a promising lad who had been cursed from birth. Or so the captain told himself as the boy turned onto his side and lay with both hands curled childishly under his cheek. But Horsa was the captain’s young brother, and Hengist had feared the prospect of losing him to suicide if the younger man had been doomed to spend the remainder of his life as a cripple. Hengist kept his own counsel, but he was sure that Vortigern was more truly a demon than this child of light. Then Hengist, mercenary and king’s man, closed his eyes and surrendered to a brief hour or two of sleep. What would come on the morrow was beyond his power to change.

Dreams chased Hengist into the darkness. He relived the murder of his father, Uictgils, in one of the bloody power struggles that occurred after the death of King Uitta of Frisia. He remembered the loneliness of being an outlander in the court of the Daneland king, Hnaef. And then the face of Myrddion loomed out of his dream like a memory of guilt. He owed the boy a bloodguilt that he would never have the opportunity to repay.

Above the boy, the oak tree shivered in the breezes that come before the dawning. Only a passing fox, returning to its den with a partridge between its teeth, scented danger and watched from the deep shadows. Myrddion awoke and saw its yellow eyes across the clearing, but he made no sound and allowed another wild thing to pass out of the sight and scent of man.

Not for the first time, the boy wished that he could live away from the prying questions and the untrusting eyes of his own kind. As he closed his eyes again, he knew that the day would bring a threat that would be far more dangerous than anything he had faced before. He would run in the wild with the fox, if he could, but he was the Demon Seed – and he had a destiny to fulfil.

CHAPTER X

DINAS EMRYS

Their first leaders were two brothers Hengist and

Horsa . . . They were the sons of Uictgils, his father

Uitta, his father Uecta, his father Uoden, from his stock

is drawn the royal race of many provinces.

Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People

The sun had risen above them when Hengist finally ordered that the horses should be forced into a gallop. Every bone in Myrddion’s body ached and he vowed to master the skills of riding if he should survive this ordeal. As the sun rose ever higher towards noon, the Saxon troop thundered through small hamlets, their conical mud huts surprisingly well tended, and the vegetable plots neat and weeded. Here was prosperity rooted in a narrow river valley of rich soil and plentiful water.

But the good earth was soon left behind the massive horses and their equally hulking riders. Now the landscape was the familiar, bitter pattern of bare earth, flint, basalt and beetling mountain peaks.

‘There, boy!’ Hengist called, and pointed his free hand towards the heights. ‘Dinas Emrys awaits you. Behold the ruined tower!’

Myrddion looked upward as his horse bunched its muscles to attack the steep path. The fortress gaped, ripped away on one side so the rooms of the main structure were partially exposed where the tower had collapsed. Huge misshapen stones lay at random beside the pathway where they had rolled from the heights. Even now, slaves and masons laboured to drag the heavier boulders back up to the plateau that was the greatest strength of the fortress.

Just when Myrddion thought his exhausted mount would founder, the captain forced the troop into a last, desperate effort to climb the slope and then, in a forecourt alive with workers and marred by fallen masonry, he ordered the Saxons to draw rein.

He threw himself from his horse’s back and lifted Myrddion from the saddle, supporting him while he struggled to restore feeling to his numbed feet. ‘I’d untie you, young Myrddion, but my master would be angered by my impertinence,’ he apologised, his face drawn at his loss of honour.

‘It’s no matter, my lord. I understand.’

‘It matters to me!’ the captain snapped as he engaged the boy’s eyes. ‘Horsa is my brother, and you healed him when another enemy would have left him to his fate. My father was Uictgils, son of Uitta Finn, kings of Frisia, and we are both honour bound to repay a debt to you. If you survive the test of the sorcerers, you may call on me and I will give you whatever help I may.’

‘Truly, Lord Hengist, you are like no Saxon that I have heard of.’

Hengist laughed. ‘Watch out, little man, and try to avoid speaking your mind quite so bluntly. King Vortigern approaches from behind you and he is a man of sudden passions, no humour and no trust in anyone or anything.’ Before Myrddion could turn, he went down on one knee in a gesture of respect to the approaching man. Oddly, he lost no dignity in this obeisance. ‘Master, I have brought the Demon Seed to you by noon today, as you commanded.’

Myrddion spun round and his upturned face felt Vortigern’s shadow blot out the sun.

Vortigern looked down and saw a child gazing up at him with eyes that were cool and appraising. Those eyes! Something in those black pools was familiar and Vortigern felt cold fingers slide sharply down his spine.

‘Demon Seed indeed!’ he muttered in response.

The boy opened those traitorous eyes very wide. Vortigern saw surprise there, and intelligence, and a fierce curiosity that the child made no effort to disguise. ‘My name is Myrddion ap Myrddion, my lord,’ he said.

‘I will call you whatever I choose.’ Vortigern flushed angrily. ‘Who are you to assume the title of the son of the lord of light?’

Myrddion looked down at his tied hands. ‘You are a king, my lord, and you can address me in any way you wish, although I would prefer my given name. I was presented to the lord of light at my birth and he accepted me as his son.’

He grinned impishly, and Vortigern felt the devastating force of his charm. Behind his back, the king made the warding sign that would protect him from evil.

‘Do you blame a nameless boy for choosing a father when he has none?’

‘Say no more, Demon Seed. Your parentage is unimportant to me – except that your father is a demon.

You

are unimportant. At sunset this evening, you will be given to the gods in sacrifice to bind the walls of my tower together. My magicians assure me that only the blood of a demon’s seed can prevent my tower from falling – again and again! What you feel or think won’t matter the slightest once darkness comes.’ Vortigern turned his attention back to Hengist. ‘Take him away and give him water. But shackle his feet. He’ll run, if given half a chance.’

Myrddion was affronted by the accusation of cowardice, and his eyes snapped briefly in anger. Once again, Vortigern felt an odd stab of familiarity, coupled with an irrational fear.

I’ve never seen this boy before, so why does he make me afraid? Where have I seen those eyes? Strange memories scurried through the High King’s mind like black rats. He shuddered, for he almost felt their scaly, prehensile tails grate against the inside of his skull.

‘Take him away, Hengist, and keep him within your sight at all times.’ He grimaced. ‘Find Rowena. I want my wife.’

Hengist intended to honour his promise to care for Myrddion, so the burly captain found a patch of shade that would grow as the afternoon advanced. Reluctantly, he obeyed his master and tied the boy’s ankles together. When Myrddion complained of thirst, Hengist held his own leather bag of water to the boy’s lips and was thanked with a brilliant, direct smile.

‘Where did you come from, Hengist? Why would you leave your home to live in these hills? Dinas Emrys is not a pleasant place.’

Disconcerted, Hengist stared at Myrddion and wondered why a child in such peril would be interested in the past life of a mortal enemy. Still, the afternoon was warm and Hengist had nothing better to do.

‘My grandfather was Uitta, the King of Frisia, but my branch of the family was very poor. The present king, who is my cousin, was suspicious of two possible claimants to the throne who were so close in blood to him, so when I was eighteen and Horsa was nine we fled northward to seek sanctuary in the halls of Hnaef, the Jute king. As an exiled mercenary, I won some renown until Hnaef died and my cousin went to war against the Jutes.’

‘Life as an exile must be almost as unpleasant as living as a demon’s seed,’ Myrddion murmured sympathetically. ‘We are both outcasts.’

Hengist laughed ironically. How strange to be pitied by a child who was about to be executed. ‘I’m still an exile, so nothing but my location has changed. We came here with other peoples from Germania to find a homeland. Yes, most are Saxons, but we are all homeless, and all landless. We are all hated for one reason or another.’

The boy said nothing. The silence drew out until Hengist felt a need to fill the aching void.

‘King Vortigern was warned by his sorcerers that his sons were unhappy with his new marriage and sought to hasten his death. I had won the respect of my men through years of bloodletting, while I accepted the coin of desperate kings. When Vortigern called for mercenaries, I saw the opportunity to have land of my own and a secure future for my sons. Cymru – or Britain – is surely big enough for all of us.’

Hengist appeared to be pleading for understanding, so Myrddion nodded. He could empathise with Hengist’s need for space of his own, but the boy knew that Britain wasn’t big enough for what Hengist represented.

‘The king called for willing warriors to come to Dyfed to serve as his bodyguard, promising us wealth and land as incentives. But I’ve nearly despaired of Vortigern, for no land has been forthcoming, and the pay is irregular – at best! We would have been better off taking what we wanted like the Saxons of Caer Fyrddin, who have made alliances with Vortigern and then settled where they chose. But I have been bound by my oath to the king.’ He paused. ‘This whole business turns my stomach. It’s superstitious nonsense. You may believe that Saxons are barbarians, but I can’t see how your blood will hold up Vortigern’s tower. Whether you are a demon or not, my honour has been besmirched by the whole search and the circumstances of your capture. But I gave my word to my master and my word is my bond. Do you understand, Myrddion? I don’t wish your shade to reproach me after you are killed.’

The boy placed his tied, long-fingered hands on Hengist’s arm in a gesture of sympathy. Hengist was shocked to see tears gathering in Myrddion’s eyes and he felt so guilty that he was lost for words.

‘I sometimes see things, Hengist,’ Myrddion whispered. ‘I try not to, because people might believe that I really

am

the child of a demon. But I know Vortigern can’t kill me, so you may be at peace on that score, my lord.’

Hengist grunted in disbelief. Then the boy’s expression suddenly stiffened, and he stared fixedly ahead.

‘I am sure, Hengist, that you will own great lands one day, and not too far in the future. You will rule a kingdom in the south and Horsa will die in the process of winning that land, but his sons and your sons will dig deep roots into these lands, even though I will fight my whole life to drive you out. You and I are brothers, Hengist, under the skin.’

‘What are you gabbling about, boy? By dawn, you’ll be dead and I’ll still be a landless warrior.’

‘Remember my words, Hengist, for we’ll not meet again once my work here is complete, although we’ll hear of each other many times in the years to come.’

The eyes of the boy seemed so large that Hengist feared he would drown in their black, lightless depths. Then Myrddion shook his head, removed his hands from Hengist’s arm and blinked rapidly as his visions faded. ‘What happened? What did I say? Was I in a fit of some kind?’

He doesn’t know what he said! Hengist thought furiously. Could the Demon Seed be a true prophet? Could he be a genuine master of the serpent gods? ‘By Baldur’s belt!’ he breathed. ‘Do you often have these lapses, Myrddion?’

‘I remember telling you that I sometimes see things, but then I felt as if I were enveloped in a thick, black fluid. I see shapes in the black water . . . armed warriors, a fortress by a great sea and a strange stone with a white horse standing beside it.’ The boy shook his head again as if to clear away the disjointed images. ‘But I swear I don’t know if the images I see are real or simply a sign of brain fever. They frighten me, because I don’t believe in such things.’