Read Climbing Up to Glory Online

Authors: Wilbert L. Jenkins

Climbing Up to Glory (17 page)

That blacks valued freedom immensely would prove to be beneficial in their struggle to combat white racial violence, which was designed to take away that freedom. Indeed, they would need all the determination they could muster to withstand the massive onslaught of white violence launched against them. Having lost the war, whites were embittered and in a state of shock. How could this have happened? they asked. How could their way of life have been destroyed? How was it possible that lowly and inferior blacks were now truly free? And how could they tolerate blacks as free individuals? The answer was that under no circumstances could they accept blacks as their equals. The only alternative was to convince blacks that while the U.S. government might recognize them as being free, Southern whites never would, even if it meant the annihilation of freedmenâa mission that roaming gangs of former Confederate soldiers would be happy to carry out.

In some areas, violence against blacks reached staggering proportions in the immediate aftermath of the war. In Louisiana in 1865 a visitor from North Carolina wrote, “they [whites] govern... by the pistol and the rifle.” “I saw white men whipping colored men just the same as they did before the war,” testified freed slave Henry Adams, who claimed that “over two thousand colored people” were murdered in 1865 in the area around Shreveport. The Freedmen's Bureau was not able to establish order in Texas, and blacks there were especially vulnerable to white violence. Blacks in the state, according to a Bureau official, “are frequently beaten unmercifully, and shot down like wild beasts, without any provocation.” A freedwoman from Rusk County named Susan Merritt remembered seeing black bodies floating down the Sabine River and said of local whites, “There sure are going to be lots of souls crying against them in Judgement.”

It was not unusual for whites to wipe out whole black communities on fabricated allegations. For example, in 1866, after “some kind of dispute with some Freedmen,” a group near Pine Bluff, Arkansas, set fire to a black settlement and rounded up the inhabitants. A man who visited the scene on the following morning described it as “a sight that apald me 24 Negro men woman and children were hanging to trees all round the Cabbins.”

109

Moreover, whites sometimes would take advantage of starving freedmen by offering them poisoned food. Annie Day explained: “I wuz told by some older niggers dat after de war and de slaves had dere freedom, de niggers was told to go to Millican. A lot of âem went down dere. Dey wuz awful hungry, and de storekeepers dere give 'em barrels of apples to eat and de apples had been poisoned, and dey killed a lot of de Colored people.”

110

Regardless of the obstacles they faced, some blacks refused to take the random violence meted out to them by whites without a fight. They employed two strategies: blacks sought to use the judicial system; and, in some cases, they took the law into their own hands. On one occasion, a poor white woman hit a black woman for no apparent reason other than the color of her skin. At first, the black woman did not complain. However, when her white neighbor struck her a second time, she retaliated. In response, the white woman had her arrested, but the black woman had already contemplated filing charges against the white woman for violating her civil rights. The judge ruled in favor of the black woman. As a result, the case was thrown out of court, and the white woman was assessed the court costs. Utilization of the judicial system, however, was often long and taxing and yielded few positive results.

Even if they banded together and took the law into their own hands to suppress crimes committed by whites against them, blacks tried to work within the system. For example, when a group of armed blacks in 1866 in Orangeburg, South Carolina, apprehended three whites who had been terrorizing freedmen, instead of lynching them, the blacks delivered them to the county jail. And when a white man was found guilty of the cold-blooded murder of a freedwoman in Holly Springs, Mississippi, blacks formed a posse to hunt him down, although there is no record of their having caught him. Some whites who assaulted blacks were, however, not so fortunate. In the Newberry district of South Carolina, two former Confederate soldiers attacked a black Union soldier. While he was struggling with them, one of the rebel soldiers stabbed him so severely that the wound was thought to be fatal. News of this confrontation quickly spread, and both rebel soldiers were apprehended by black soldiers of the regiment to which the injured soldier belonged. Within three hours the Confederate who had stabbed the Union soldier was tried, found guilty, shot, and buried.

111

Certainly, the second rebel would have undergone a similar fate had he not managed to escape.

Many blacks in the South looked to the Cherokee Nation as a haven. Although racism existed among the Cherokees, blacks were treated in the Nation better than they were in the American South. Unlike the Southern whites who often indulged in mob violence, the Cherokees did not. In fact, there is no record of a lynching among them. Freedmen there did not fear for their personal safety, and they were assured of a hearing before a properly constituted tribunal.

112

Moreover, the Choctaws and Chickasaws had few difficulties with their freedmen, as cases of violence involving them were relatively few. Ironically, the racial tension that existed in both Nations was the result of confrontations between freedmen from Southern states and their white counterparts who moved to the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations after the war. Of course, the Southern whites who moved into the Chickasaw Nation brought with them their old bigotry. Ardmore and other towns in the Indian Territory became the home of active Confederate veterans' organizations. As expected, racial prejudice against blacks ran high among the white population of the region that later would become known as “Little Dixie.” Indeed, if crimes were committed, blacks were looked upon with suspicion. Visitors were asked to leave town if they could not convince local whites that they had business in the area. Not surprisingly, fistfights were common on the streets. If the fight was between two blacks, it became a spectacle, as people gathered and began to cheer for one or the other. However, if the fight was between a black and a white, racial tensions ran high and the fight would likely spread to onlookers.

113

Despite the many trials that blacks had to endure during the early years of emancipation, they remained undaunted. They were determined to enjoy the fruits of their newfound freedom to the fullest. Whites could continue to employ whatever measures they devised to deny them full autonomy, but it would be to no avail. At long last savoring the sweetness of liberty, the black people could now shout, “Free at last; Free at last; Thank God Almighty, we are free at last.”

114

A “WORKING CLASS OF PEOPLE”

The Struggle to Gain Economic Independence

Â

Â

Â

Â

THE WARTIME PROSPERITY continued into the postwar years in the North, but in the South towns and cities lay in ruins. Plantations were wrecked, and neglected fields were overgrown with grass, weeds, and wildflowers. Bridges and railroads were destroyed. White Southerners had lost much of their personal property in the war, including, because of emancipation, about $2 billion worth of slaves. Furthermore, Confederate bonds and currency were now worthless. These losses were a huge blow to the economic future of Southern whites. Many of them faced the prospect of starvation and homelessness. Even some of those who had earlier been counted among the wealthy would now be able to survive only on government rations.

1

While conditions were bad for Southern whites, they were even worse for Southern blacks. Four million black men and women were now emerging from slavery. They and their ancestors had been held in bondage for nearly two and one-half centuries. Once they were emancipated, many left the plantations in search of a new life in freedom, walking to the nearest town or city or roaming the countryside and camping at night on the bare ground. Most of these people had no more possessions than the clothes they wore, and often these were merely old sacks tied together and socks instead of shoes. The new freedmen were overwhelmingly unskilled, illiterate, and poor. Moreover, since responsibility for their well-being had always been assumed by the master, they had little knowledge about how to survive on their own.

2

Now that blacks were no longer under the direct supervision of whites, the nation looked in 1865 at its now-large free black population in the South and wondered: Will they work to provide for themselves and their families? Will they rely on government handouts? Will they become parasites or beggars? Will a large number of them become criminals? The answers to these questions proved that the former slaves had definite ideas about how free men and women should conduct themselves.

Contrary to the belief held by most Southern whites that blacks would not work without being forced to, most freed slaves were willing under emancipation to provide for themselves and their families. The editor of a black newspaper declared in 1865 that black people need not be reminded to avoid idleness and vagrancy. After all, he concluded, “the necessity of working is perfectly understood by men who have worked all their lives.” For example, at Augusta, Georgia, a convention of freedmen discountenanced vagrancy and encouraged every one of their group to obtain employment and labor honestly.

3

Blacks had established a remarkable work record under slavery, and as free men and women they were determined not to blemish that record. A resolution was passed at a convention of freedmen in Hampton, Virginia, asserting that they were capable of maintaining themselves in their new situation. They argued that any one advancing a different viewpoint was either purposely misrepresenting them or was ignorant of their capabilities.

4

Furthermore, if any class could be considered lazy, they stated, it would be the planters who had lived in idleness and on forced labor all their lives. One scholar posits that “blacks brought out of slavery a conception of themselves as a âWorking Class of People' who had been unjustly deprived of the fruits of their labor.”

5

The efforts of blacks throughout the South to secure employment during Reconstruction lends credence to their claim of being a working class of people. Of course, many toiled on farms and plantations. Some found jobs in factories and on railroads, and as janitors, porters, stevedores, tailors, longshoremen, painters, carpenters, blacksmiths, tanners, firemen, and even law enforcement officers. Others went into service, performing such tasks as washing clothes, cleaning, cooking, and sewing. Still others worked as nannies and midwives. In addition, due in large part to poverty, prostitution flourished in many of the South's towns and cities, and black as well as white women supported themselves in that way. Since prostitutes generally made more money than farm workers or domestics, they were willing to risk violence, arrest, disease, and early death. Prostitution was generally segregated but not always. For example, it was rumored that Celia Miller in Galveston, Texas, in 1867 kept a nondiscriminatory “disorderly house” where both white and black women lived and worked.

6

In general, not only were blacks working, but it also was a universal observation among Southern whites that they worked well when paid. One hotelkeeper, for instance, informed Sidney Andrews, a Northern white traveler, that he was doing well with his black labor. He asserted, “I treat âem just as I would white men; pay them fair wages every Saturday night, give 'em good beds and a good table, and make âem toe the mark. They know me, and I don't have the least trouble with 'em.”

7

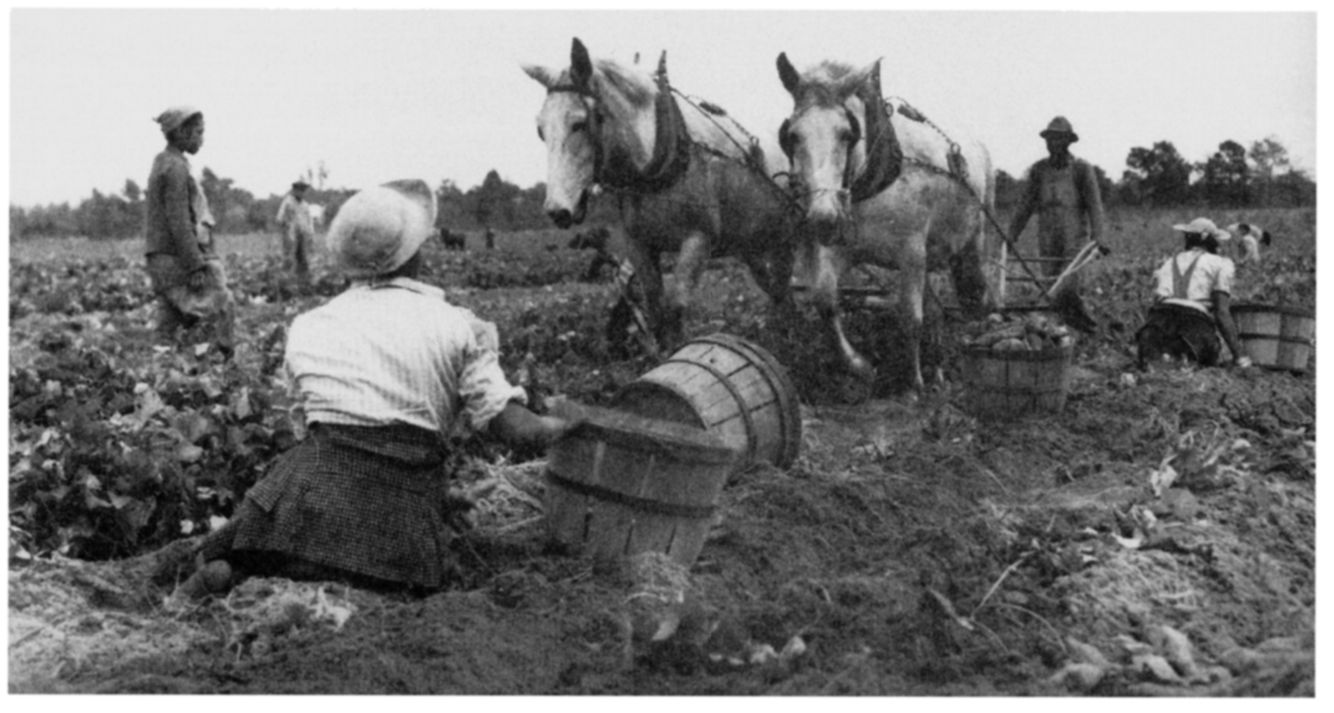

FORMER SLAVES UNDERTAKING FARM WORK IN THE SOUTH.

Courtesy of the North Carolina Division of Archives and History

The Federal government gave some help to blacks in their struggle to survive as free men and women. In March 1865, Congress created the Freedmen's Bureau to help oversee what it hoped would be the peaceful transition of blacks from slavery to freedom. The Bureau was intended to function like a primitive welfare agency, providing food and clothing to freedmen and to white refugees. It was also authorized to distribute up to forty acres of abandoned or confiscated land to black settlers and loyal white refugees and to draft and enforce labor contracts between freedmen and planters. The Bureau cooperated with the Northern voluntary associations that sent missionaries and teachers to the South to establish schools for former slaves, and it achieved a measure of success in the area of black education. Its record in other areas was mixed, however. It distributed virtually no land to former slaves. Indeed, Bureau officials would often collaborate with planters in expelling blacks from towns and cities and forcing them into signing contracts to work for their former masters.

8

Although Southern whites accused freedmen of relying on government assistance, in some places more whites than blacks benefited from this aid. In fact, it was far more easy for whites to accept government help than it was for blacks. Many freed people, embarrassed by their needs, disdained such handouts in favor of providing for themselves if at all possible. After emancipation, needing the assistance of whites may well have been too reminiscent of the time under slavery when they had to take whatever food and clothing was allotted to them by their masters. As free men and women, they felt obliged to provide for their families and themselves to the best of their abilities. It is no wonder that Sarah Chase, a Northern white schoolteacher, wrote from Richmond in May 1865 in reference to freedmen that “most of these people will not beg.” In order to bring her point home, Chase told a story about a black woman with several small children who asked her for a job: “for something, missusâanything to be earning a little something.”

9

Given the fact that the Freedmen's Bureau usually would not supply rations to freedmen unless they were old or decrepit, it proved beneficial to blacks to display independence and self-reliance.

Freedmen tried to take some control of the conditions under which they labored. As free men and women, they refused to continue working in gangs under the direction of whites as they had done during slavery. They also demanded that their employers give them time off to devote to their own chores. Convinced that working at one's own pace was part of freedom, they simply would not labor as long or as hard as they had in slavery.

“The ex-slaves seemed to see in land ownership, the symbolic and actual fulfillment of freedom's promise,” according to one contemporary historian. The slogan “forty acres and a mule” epitomized the longing of former slaves to acquire land and, through it, economic independence and the certainty that they could provide for their families.

10

Without land, most freedmen believed that they would always be slaves. One elderly freed black posed a heart-felt question to journalist Whitelaw Reid in 1865: “What's de use of being free if you don't own land enough to be buried in?” The old man then answered his question: “Might juss as well stay [a] slave all yo' days.”

11

“Gib us our own land and we can take care ourselves, but widout land, de ole massas can hire us or starve us, as dey please,” said one South Carolina black.

12

And a Mississippi black remarked, “All I wants is to git to own fo' or five acres ob land, dat I can build me a little house on and call my home.”

13

That blacks would have a passion for the land should come as no surprise. They had worked the soilâplantâing, cultivating, harvesting, tending gardensâand raised livestock for generations. Like most rural people, blacks respected the land and its bounty. Although their owners legally owned the property on which slaves had their garden plots, some blacks had felt a certain proprietorship over these plots.

14

Moreover, the passion for owning a small piece of land shown by North American blacks is not unusual when compared to the experience of other postemancipation societies. In the aftermath of slavery, freedmen throughout the Western Hemisphere in Haiti, the British and Spanish Carribean, and Portuguese Brazil all saw ownership of land as crucial to ensuring their economic independence.

15

FORMER SLAVES TOILING ON THE LAND, LOCATION NOT KNOWN.

Courtesy of the North Carolina Division of Archives and History

In early 1865 many former slaves believed that, having set them free, the Federal government would now give them forty-acre plots taken from the plantations on which they had previously been confined. Lizzie Norfleet remembered that “the report came out after the war that every family was going to get forty acres and a mule to start them out.” However, the government did not make good its promise because “I ain't never seed nobody what received nothing.”

16

Charlie Holman stated that “dey said they was gonna give us so much land an' a mule but we never did get that.”

17

Sally Dixon maintained that “we was told when we got freed we was going to get forty acres of land and a mule. Stead of that we didn't get nothing.”

18

Echoing similar sentiments, Berry Smith asserted, “Dere was a heap of talkin' after de war, about every nigger was goin' to git forty acres an' a mule, an' had us all fooled up, but I ain't seen my mule yit. I never did see nobody git nothin!”

19

Why did so many former slaves expect the government to give them forty acres of land and a mule? General Oliver O. Howard, the commissioner of the Freedmen's Bureau, argued that the myth of land redistribution in the South probably arose from the wording of the law establishing the Bureau. This might have been the case, but, if so, it appears that the government purposely misled the freedmen. As noted, the Bureau was authorized to distribute up to forty acres of abandoned or confiscated land to black settlers. In General Howard's opinion, land speculators should have been blamed for spreading the rumor. The intention of the speculators, he argued, was to lower the value of the land.

20

Elizabeth Hyde Botume, a Northern white teacher among Sea Islands blacks, maintained that white and black Union soldiers convinced many freedmen that they would be given the land of their former owners.

21

Indeed, Andrew Boone recalled that “shortly after the Union troops arrived in his community ... a story went round an' round dat de marster would have to give de slaves a mule an' a years' provisions an' some lan', about forty acres.”

22

Moreover, some Southern white civilians and Confederate soldiers believed that land would be given to former slaves and thus helped spread the rumor. For example, a prominent white Georgian, James T. Ayers, wrote in his diary in early February 1865: “I really think this whole South, or that part called South Carolina with a large portion of Georgia and Florida will be gave to the niggers for a possession.”

23

Freedmen thought that they had a moral right to the land. This sentiment is expressed in a statement issued by freedmen in Virginia in protest against their removal from a contraband camp there in 1866: “We has a right to the land where we are located. Our wives, our children, our husbands, has been sold over and over again to purchase the lands we now locates upon; for that reason we have a divine right to the land.... And den didn't we clear the land, and raise de crops ob corn, ob cotton, ob tobacco, ob rice, ob sugar, ob everything? And den didn't dem large cities in de North grown up on de cotton and de sugar and de rice dat we made? ... I say dey has grown rich, and my people is poor.”

24

Emancipation would usher in a new economic order as compensation for their years of involuntary work on the land, they believed. A black preacher in Florida told a group of fieldhands, “It's de white man's turn ter labor now... whites would no longer own all the land, fur de Gouvernment is gwine ter gie ter evâry nigger forty acres of lan' an' a mule.”

25

One confident Georgian offered to sell to his former master his share of the plantation that he expected to receive after the Federal redistribution.

26

Eli Coleman told his reviewer in the 1930s that “it looks like the Government would have give us part of our Maser's land cause everything he had or owned the slaves made it for him.”

27

Agreeing with this view, William Coleman remarked, “They should have give us part of Maser's land as us poor old slaves we made what our Masers had.”

28

While it appeared initially that the government would grant land to freed blacks in the South, for the masses of them, this never happened. As early as January 1865, General William Tecumseh Sherman responded to the large numbers of freedmen who flocked to his lines by designating all the Sea Islands south of Charleston and all abandoned rice fields along rivers up to thirty feet deep as areas for black settlement. Black families were to be settled on 40-acre plots and given “possessory title.”

29

Given Sherman's negative racial attitude and the fact that he allowed his white soldiers on at least one occasion to kill black recruits, it is ironic that he would issue an order granting land to freedmen. Apparently, Sherman hoped by such an order to get rid of the thousands of blacks who followed his army, to keep black males out of the Union army, and to grievously injure the morale and material fortunes of his enemies. Southern whites, he reasoned, would be humiliated and publicly insulted by the very thought that their former slaves would own their land.

30

What could better demonstrate the powerlessness of Southern whites before their enemy?

Special Field Orders No. 15 thereafter was the principal topic of conversation in black communities throughout the South. For example, blacks in Savannah held a meeting on February 2,1865, at the Second African Baptist Church attended by General Rufus Saxton, whom Sherman had placed in charge of the land distribution program, and his staff. The meeting attracted so much interest that the building was packed to capacity, and hundreds of freedmen were turned away. When Saxton said, “I have come to tell you what the President of the United States has done for you,” the audience responded with emotion, “God bless Massa Linkum.” Hymns were sung, tears were shed, prayers and thanks were given to God, and men began preparing for a life on their own land.

31

Once assured of the legality of General Sherman's Special Field Orders No. 15, General Saxton, an assistant commissioner of the Freedmen's Bureau, proceeded to implement the Bureau's program of land redistribution. These early government policies were never carried out because President Andrew Johnson's Amnesty Proclamation of May 1865 pardoned former Confederates and restored all their property rights to them, except the right to own slaves.

In October 1865, Johnson instructed General Howard to inform Sea Islands blacks that they would have to return the land they occupied to white planters. Howard, who considered himself a friend of blacks and fully understood the importance they attached to land ownership, reluctantly obeyed Johnson's order. When he told freedmen that they must give up their land, some of them wept, protesting, “Why do you take away our lands? You take them from us who have always been true, always true to the Government! You give them to our all-time enemies! That is not right.” Union soldiers forced them to leave or stay on and work for their former masters.

32

But they were not removed without a fight. Sea Islands blacks and freedmen throughout the South, determined to hold onto land whatever the cost, battled with plantation owners and local and Federal law enforcement officials. For example, a dozen or more freedmen were living on Celey Smith's farm in Elizabeth City County, Virginia, where they had built homes and were supporting themselves by their crops. They met the sheriff with loaded muskets when he came to oust them and informed him that they would “yield possession only to the U.S. Government.” In spite of sheriffs, deeds, or writs, black settlers in Norfolk County, Virginia, also refused to give up their land. Ultimately, Governor Gilbert Walker instructed county officers to intervene as the freedmen fought a pitched battle with county agents until overcome by superior numbers. Moreover, near Richmond, 500 freedmen armed themselves and defied authorities to put them off the land. Federal forces forced them to vacate and then burned to the ground the houses that they had built.

33

Although black women played a significant role in the struggle to hold onto the property of white slaveowners, it has largely gone undocumented. In South Carolina's Low Country, for instance, Charlotte and Sarah, two among more than 260 former slaves who had occupied and cultivated the Georgetown plantation Weehaw for over a year on their own, opposed the owner when he returned in 1866. Charlotte, Sarah, and Fallertree attacked him and tried to take control of the plantation. Charlotte's role in the attack must have been especially egregious, for while Sarah and Fallertree received lesser sentences, Charlotte was sentenced to thirty days in the Georgetown jail. A critical part in the defense of Keithfield plantation against restoration was also played by eight or ten freedwomen, who in March 1865 drove away the white overseer. As a consequence, the 150 freed people were able to work the plantation on their own for the remainder of the year.

34

This luxury came to an end at the beginning of the new year, when Keithfield's absentee owner, a widow, asked a neighboring planter to help her retake control. The neighbor was no other than Francis Parker Sr., probably the white man most hated by blacks in the region. During the war, Parker had served as the local Confederate provost marshal and had helped carry out the public execution of recaptured fugitive slaves. He hired Dennis Hazel, the former slave driver, as overseer. With the employment of these two men, the potential for conflict escalated. There was absolutely no way that the freedmen and women would relinquish Keithfield without a battle, especially with Parker and Hazel as their antagonists. Thus, when Parker sent his son and Hazel to the plantation to resume control, the work gang turned their toolsâ“Axes hatchets hoes and poles”âinto weapons and attacked Hazel, threatening to kill him.

35

Hazel was fortunate to escape with his life but returned to the plantation a few hours later with Parker's son and two soldiers. They would have been better off not to have appeared, for the blacks assaulted them with their tools and pelted them with bricks and stones. Armed with heavy clubs, Sukey and Becky entered the fray. Aided by Jim, they exhorted their fellow laborers to join the fight, “declaring that the time was come and they must yield their lives if necessaryâthat a life was lost but once.” Eight to ten “infuriated women” now swelled the crowd. Among this group were Charlotte Simons, Susan Lands, Clarissa Simons, Sallie Mayzck, Quahuba, and Magdalen Moultrie, armed with heavy clubs and hoes and backed by four or five men. They focused their attack on Hazel, and, as a result, the soldiers' efforts to defend the slave driver from their blows were “entirely ineffectual.” The women continued to beat Hazel, Parker, and the two soldiers. Parker, followed by Hazel, made the only escape he could, by jumping into the river and swimming away “under a shower of missiles.” The soldiers, bloodied and disarmed, made their own escape by foot.

36