Climbing Up to Glory (4 page)

Read Climbing Up to Glory Online

Authors: Wilbert L. Jenkins

Lincoln's state-run compensated emancipation scheme contained several weaknesses. Fundamentally it was far more sensitive in its appeal to whites to accept the process than it was in foreseeing the consequences for blacks. The prospect of civil and political rights for blacks would surely have been limited had states and the existing white leadership of 1862 retained control over emancipation. Since it would have been implemented before blacks proved their capacities and earned national obligation by their service in the war, it is likely that state-controlled emancipation would not have advanced the course of black rights very much. No national power would have been able to checkmate local oppression of blacks under Lincoln's state-controlled emancipation scheme, since no Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments would have been on the horizon.

36

The second part of Lincoln's plan was a proposal to ship slaves and free blacks out of the country. Deportation would rid the nation of slavery and all African Americans along with it. Again, Congress supported the president. In spring 1862 it voted to appropriate $600,000 for the purpose of colonizing slaves and free blacks.

37

Afterward, Lincoln began to launch a campaign to persuade free blacks to agree to be colonized and endeavored to find somewhere for them to settle. On August 14 he met with a delegation of five free black men, led by Edward M. Thomas, and tried to persuade them that all blacks would be better off if they were to leave the United States and resettle in Liberia, Central America, or the Caribbean.

38

Like Thomas Jefferson, Lincoln believed that blacks were innately inferior to whites and that it would be impossible for blacks and whites to live together in the United States as equals.

39

Thus, Lincoln had come to believe that colonization was the only viable solution to the race problem in America. He expressed the sentiments of many whites, as few of them could contemplate a situation where all blacks were free. One of the most ardent defenders of the white South and its institutions, Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, expressed the view in 1830 that it “would be unwise” to liberate the slaves “without their removal or colonization.” One Mississippi farmer believed that “the majority would be right glad [to abolish slavery] if we could get rid of the niggers. But it wouldn't never do to free âem and leave 'em here. I don't know anybody hardly, in favor of that.”

40

Most black leaders, however, were furious with Lincoln for suggesting that they should abandon the only country they had known. They were adamantly opposed to all colonization schemes, believing that blacks, as productive members of society, had just as much right to live in the United States as did whites. Like whites, their ancestors had helped build America into what it now wasâa powerful, though divided, nation. Their forebears had fought, bled, and died for the country in all the wars that the nation had been engaged in. Furthermore, some free blacks believed that if they left the country, their brothers and sisters who were held as slaves in the South would be left even more vulnerable to white oppression. They expressed their anguish in open letters. Frederick Douglass, for example, in the pages of his newest publication,

Douglass Monthly,

in September 1862 asserted that “Mr. Lincoln assumes the language and arguments of an itinerant Colonization lecturer, showing all his inconsistencies, his pride of race and blood, his contempt for Negroes and his canting hypocrisy.”

41

Free blacks in various cities held protest meetings condemning the president's colonization scheme. The general sentiment of these gatherings was expressed as an “Appeal” sent to Lincoln by free blacks in Philadelphia: “Many of us have our own house and other property, amounting in the aggregate, to millions of dollars. Shall we sacrifice this, leave our homes, forsake our birthplace, and flee to a strange land, to appease the anger and prejudice of the traitors now in arms against the government?”

42

Not all free blacks were opposed to colonization. Alienated by discrimination and abuse, some grasped at the opportunity. Hundreds emigrated to Haiti during the first year of the war. By 1862, promoters were touting Central America as a new destination, and some free blacks petitioned the U.S. government in efforts to acquire financial backing to emigrate there. The Reverend Henry M. Turner, a prominent clergyman in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, was among the signers of one of these petitions. Free blacks in support of colonization, however, represented a small minority.

43

Without the support of Northern free blacks, it was unlikely that any colonization scheme would succeed. Lincoln's efforts to locate a place where blacks could create a new life for themselves proved as fruitless as his efforts to persuade them to leave America. Although representatives from the government of Liberia had assured the president that black Americans would be welcome in their country, Lincoln did not regard Liberia as the most feasible place for black resettlement because it was so far from the United States. He preferred somewhere closer. Chiriqui, a province of Colombia (now in Panama), appeared to be satisfactory to him. In attempting to make the necessary arrangements, however, Lincoln allowed himself to negotiate with members of a fraudulent land company. As a consequence, the project collapsed. Moreover, Colombia's neighbors in Central America had protested vigorously against the proposal. Once Lincoln had abandoned the Chiriqui scheme, he tried to persuade the European powers that owned territories in Latin America to provide a place for blacks to be colonized. But these powers saw no political dividends therein and were not responsive to his overtures. By October 1862, Lincoln had nearly exhausted all his options for colonization in the Western Hemisphere. His last remaining one was Haiti, but, here again, he made the mistake of dealing with land speculators of questionable honesty. Late in December, Lincoln signed a contract with Bernard Kock for the settlement of five thousand blacks on Cow Island in Haiti but was saved from further embarrassment by Secretary of State William H. Seward, who was suspicious of Kock's integrity and refused to certify the contract. Thus, by the fall of 1862 neither of Lincoln's plans for compensation and colonization had caught on.

44

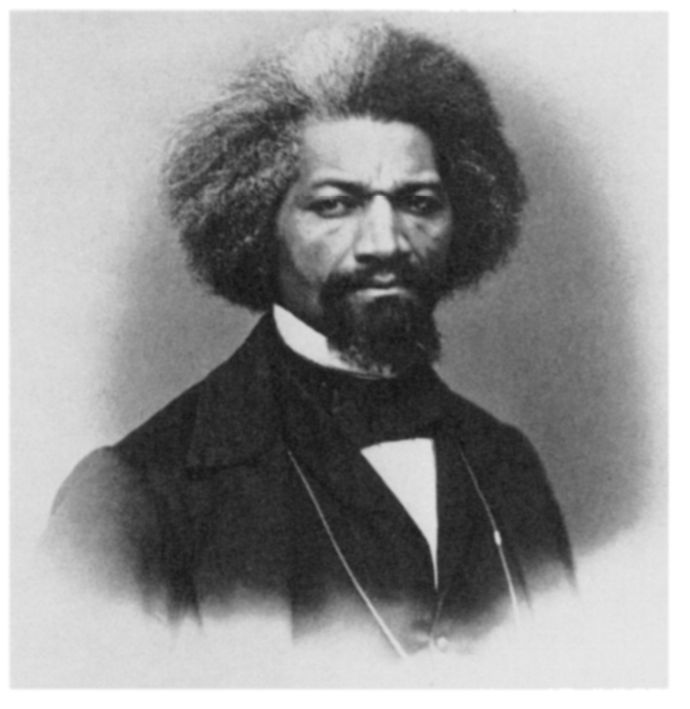

FREDERICK DOUGLASS, THE CELEBRATED ABOLITIONIST, UNION RECRUITER, FEMINIST, AND SOCIAL ACTIVIST.

Library of Congress

During the summer of 1862, while Lincoln tried to work out a plan for the colonization of blacks, he was facing increasing pressure from black and white abolitionists and from the more progressive elements of his party for a commitment to end slavery. Furthermore, it had become clear to the president and other government officials that the war would be long and bloody. Lincoln was confronted with Confederate resistance that was more massive and effective than he had thought possible. He had believed that the Union was on the verge of victory in the spring of 1862, but any hope of success at that time was shattered by General Robert E. Lee's successful counteroffensives in the Seven Days. As he wrestled with the problem of emancipation, he also worried how he could meet the spiraling demands on Union manpower for both combat and logistical duties. By linking emancipation with arming the former slaves, he found a solution. As a war measure, he would issue a proclamation freeing the slaves. He first mentioned this possibility to his cabinet in the summer of 1862, knowing that he had to move cautiously. Politically and strategically, he was restrained by the fear that forced emancipation would turn the loyal Border states of Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland against the Union. The loss of these states' vital industry and manpower would hurt the Union cause. Furthermore, Lincoln did not want to do anything that would provoke the lower Southern states to launch a war of total resistanceâsomething they were likely to do if he were to free the slaves in that section of the country.

45

In the end, Lincoln recognized that the Confederate war effort that to date had resisted Union advances was vulnerable at one major point: it rested on an economy and a social structure that depended on slave labor. The only way to combat it effectively was to undermine it by removing that base. Thus, Lincoln argued in July 1862 that a proclamation of emancipation “was a military necessity absolutely essential for the salvation of the Union.” Furthermore, “we must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued.”

46

And so, on September 22,1862, just five days after the Union victory at Antietam, Lincoln decided to act, proclaiming that on January 1, 1863, “All persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of the state, the people whereof shall be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

47

The Emancipation Proclamation stipulated that freed slaves would be accepted by the Union military “to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.”

48

In this document he also revived the possibility of compensated emancipation and said that he would continue to encourage the voluntary colonization of blacks “upon this continent or elsewhere.”

49

Lincoln, therefore, either continued to believe that white hostility would be too massive for emancipated blacks to live in the same vicinity with whites, or still thought that blacks were inferior to whites and could never live as equals in society. Perhaps he was also trying to placate Northern whites, many of whom were fearful that emancipated blacks would settle in the North. If they were to be colonized somewhere in Central America, there was no need to worry.

When news of Lincoln's preliminary proclamation reached the South, slaves by the thousands responded by fleeing plantations and rushing into the lines of the Union army. Years later, Mary Crane, a former slave, recalled the event in Larue County, Kentucky: “When President Lincoln issued his Proclamation, freeing the Negroes, I remember that my father and most all of the other younger slave men left the farms.”

50

Most slaves were illiterate, but the news of emancipation reached them through an oral network called the “grapevine telegraph.”

PRESIDENT ABRAHAM LINCOLN, WITH CABINET MEMBERS, ISSUING THE EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION.

Library of Congress

Gabe Butler, for example, found out about the Emancipation Proclamation in this way: “I didn't hear much talk âbout de war, but slaves wud cum frum udder plantations an' dey wud tell how old man Abe was going to sot us free.”

51

Thomas Rutling learned about it from his master's son, a medical doctor who did not support slavery. Rutling was sitting in the slave quarters waiting for breakfast when the young doctor came along and spoke to his brother and sister at the front door. His siblings “jumped up and down, and shouted, and sang, and then told me I was free.”

52

Benjamin Holmes, a slave in Charleston, South Carolina, read Lincoln's entire Proclamation to a group of slaves who reacted with loud rejoicing.

53

In Louisiana,

LâUnion,

a French-English journal started by free blacks in New Orleans in September 1862, spread the news and urged all black men in the state to make the best of their new opportunities “in freedom.”

54

Blacks in Union-held territory such as the Sea Islands of South Carolina were informed by Union officials. The Sea Islands blacks were so overcome with joy at services held to celebrate the Proclamation that they began to sing, “My Country, 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing!”

55

In addition, Susie King Taylor, on hearing it read, described January 1,1863, as a “glorious day.”

56

Pierce Harper was also in Union-held territory when the news reached him. Union officials “read it to all de colored people who went to town an' had men go âround an' read it to de ones dat didn't get to town.” Once all the blacks returned to the plantation, the celebrating began. Harper remembered “how dey stayed up half de night at Mr. Harper's after de men had read de âmancipation to us, singing an' shouting. Dat was all dey did, jus' sing an' shout an' go on.”

57

Despite these efforts because of the effectiveness of white owners in withholding information from their slaves, a large number did not know of the Proclamation for several months after it was issued. In fact, one former slave recalled not having heard of it as late as 1864: “De White folks nebber talk âfore black men, dey mighty Free from dat.”

58

Lincoln had earlier predicted with great enthusiasm that the Proclamation would immediately lead to a mass exodus of blacks to Union lines. This did not happen, causing Lincoln to say with concern a few months after the Proclamation was announced that “the slaves are not coming so rapidly and so numerously to us as I had hoped.”

59

Thus, August 1863, Lincoln proposed a daring, even revolutionary, secret plan to remedy the problem. This plan called for Frederick Douglass to organize a band of black “scouts” to pass through Union lines into the plantation South “and carry the news of emancipation, and urge the slaves to come within our boundaries.” Although Douglass agreed with Lincoln's goal of informing the slaves about the Proclamation, he thought that the president's secret plan was suicidal, akin to the original plan of John Brown at Harpers Ferry. A few days later Douglass offered a counterproposal calling for the employment of agents who would infiltrate the South “to warn [the slaves] as to what will be their probable condition should peace be concluded while they remain within the Rebel lines; and more especially to urge upon them the necessity of making their escape.”

60

At the tender age of fifteen, George Washington Albright was employed as one of the agents who carried from plantation to plantation the news that the Emancipation Proclamation had been signed in Washington. Albright explained the nature of this process: “I traveled about the plantations within a certain range, and got together small meetings in the cabins to tell the slaves the great news. Some of these slaves in turn would find their way to still other plantationsâand so the story spread. We had to work in dead secrecy; we had knocks and signs and passwords.”

61

As a consequence of this successful plan, Albright maintained thousands of slaves were apprised of the Proclamation. The black men and women who served as agents showed great courage, as this was a dangerous enterprise. Detection was possible at anytime. All it would take was the confession of a nervous or loyal slave to the owner that an outsider was disseminating such news and encouraging them to run away. Certainly, if caught, the punishment would be death.

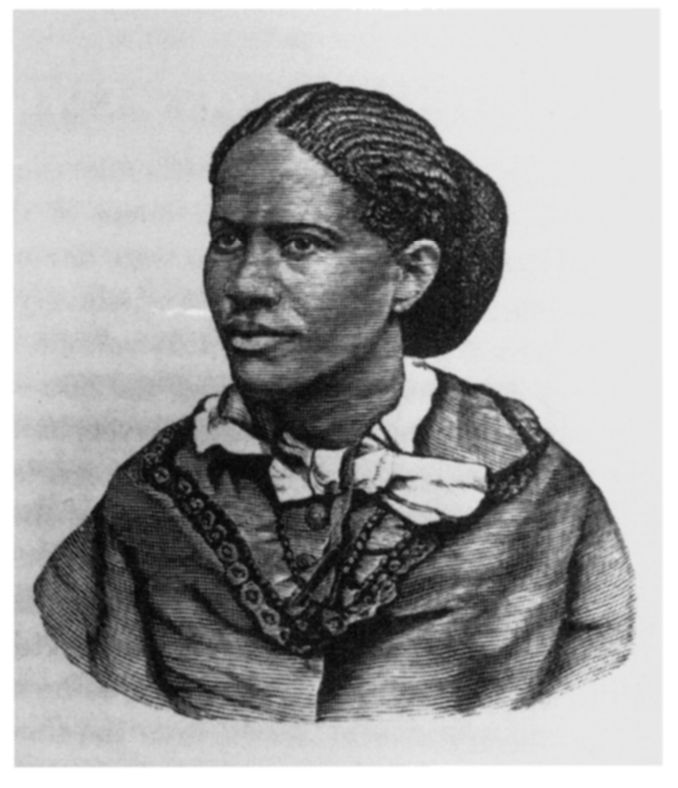

MRS. FRANCES E. W. HARPER, AN OUTSTANDING POLITICAL AND SOCIAL ACTIVIST.

Library of Congress

Northern free blacks so anxiously awaited Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation that in many cities they arranged celebratory meetings of prayer and thanksgiving on the eve of its announcement. One such meeting took place in Boston and was attended by such prominent black leaders as J. Sella Martin, William Wells Brown, and Frederick Douglass.

62

When the actual document was proclaimed on January 1, 1863, these meetings grew in number and intensity. On New Year's Day, hundreds of blacks gathered in Washington, DC, outside the White House and cheered the president, calling out to him, as the black pastor and future Reconstruction politician Henry M. Turner recalled, that “if he would come out of the palace, they would hug him to death.”

63

A Pennsylvania gathering declared that “we, the Colored Citizens of the city of Harrisburg, hail this 1st day of January, 1863, as a new era in our country's historyâa day in which injustice and oppression were forced to flee and cower before the benign principles of justice and righteousness.”

64

Echoing the sentiments of most abolitionists and Northern free blacks who thought that the Proclamation was only a stride toward freedom and complained that Lincoln had not gone far enough, the black Pennsylvanians further declared, “We would have preferred that the proclamation should have been general instead of partial, but we can only say to our brethren of the âBorder States,' be of good cheerâthe day of your deliverance draweth nigh.”

65

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, a black leader, regarded the announcement as “a day for poetry and song.”

66

And Frederick Douglass was almost overcome. “We shout for joy that we live to record this righteous decree,” he wrote .

67

Northern and Southern white reaction to the Emancipation was varied.

68