Closing the Ring (2 page)

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #Great Britain, #Western, #British, #Europe, #History, #Military, #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #War, #World War II

* * * * *

The Battle of the Atlantic was the dominating factor all through the war. Never for one moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea, or in the air, depended ultimately on its outcome, and amid all other cares we viewed its changing fortunes day by day with hope or apprehension. The tale of hard and unremitting toil, often under conditions of acute discomfort and frustration and always in the presence of unseen danger, is lighted by incident and drama; but for the individual sailor or airman in the U-boat war there were few moments of exhilarating action to break the monotony of an endless succession of anxious, uneventful days. Vigilance could never be relaxed. Dire crisis might at any moment flash upon the scene with brilliant fortune or glare with mortal tragedy. Many gallant actions and incredible feats of endurance are recorded, but the deeds of those who perished will never be known. Our merchant seamen displayed their highest qualities, and the brotherhood of the sea was never more strikingly shown than in their determination to defeat the U-boat.

* * * * *

Important changes had been made in our operational commands. Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, who had gone to Washington as head of our Naval Mission, had been recalled in October 1942 to command the Allied Navies in “Torch.” Admiral Sir Percy Noble, who at “Derby House,” the Liverpool headquarters of the Western Approaches, had held the commanding post in the Battle of the Atlantic since the beginning of 1941, went to Washington, with his unequalled knowledge of the U-boat problem. In February 1943 Air-Marshal

Slessor became Chief of the Coastal Air Command. These arrangements were vindicated by the results.

The Casablanca Conference had proclaimed the defeat of the U-boats as our first objective. In March 1943 an Atlantic Convoy Conference met in Washington, under Admiral King, to pool all Allied resources in the Atlantic. This system did not amount to full unity of command. There was well-knit co-operation at all levels and complete accord at the top, but the two Allies approached the problem with differences of method. The United States had no organisation like our Coastal Command, through which on the British or reception side of the ocean air operations were controlled by a single authority. A high degree of flexibility had been attained. Formations could be rapidly switched from quiet to dangerous areas, and the command was being reinforced largely from American sources. In Washington control was exerted through a number of autonomous subordinate commands called “sea frontiers,” each with its allotment of aircraft.

* * * * *

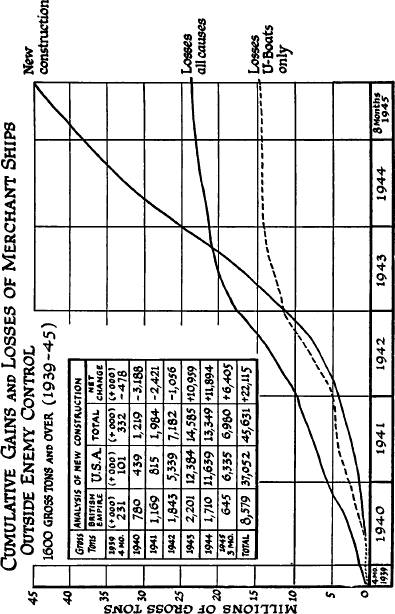

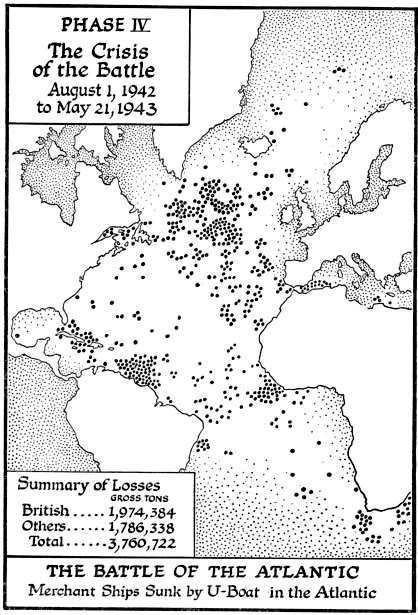

After the winter gales, which caused much damage to our escorts but also checked the U-boat attack, the month of February 1943 had shown an ugly increase in the hostile concentrations in the North Atlantic. In spite of heavy losses, the number of operational U-boats at Admiral Doenitz’s disposal at the beginning of the year rose to two hundred and twelve. In March there were over a hundred of them constantly at sea, and the packs in which they hunted could no longer be evaded by skilful routeing. The issue had to be fought out by combined sea and air forces round the convoys themselves. Sinkings throughout the world rose to nearly seven hundred thousand tons in that month.

Amid these stresses a new agreement was reached in Washington whereby Britain and Canada assumed entire responsibility for convoys on the main North Atlantic route to Britain. The decisive battle with the U-boats was now fought and won. Control was vested in two joint naval and air headquarters, one at

Liverpool under a British and the other at Halifax under a Canadian admiral. Naval protection in the North Atlantic was henceforward provided by British and Canadian ships, the United States remaining responsible for their convoys to the Mediterranean and their own troop transports. In the air British, Canadian, and United States forces all complied with the day-to-day requirements of the joint commanders at Liverpool and Halifax.

The air gap in the North Atlantic southeast of Greenland was now closed by means of the very long-range (V.L.R.) Liberator squadrons based in Newfoundland and Iceland. By April a shuttle service provided daylight air-cover along the whole route. The U-boat packs were kept underwater and harried continually, while the air and surface escort of the convoys coped with the attackers. We were now strong enough to form independent flotilla groups to act like cavalry divisions, apart from all escort duties. This I had long desired to see.

* * * * *

It was at this time that the H

2

S apparatus, described in Volume IV, page 280, of which a number had been handed over somewhat reluctantly by our Bomber Command to Coastal Command, played a notable part. The Germans had learnt how to detect the comparatively long waves used in our earlier radar, and to dive before our flyers could attack them. It was many months before they discovered how to detect the very short wave used in our new method. Hitler complained that this single invention was the ruin of the U-boat campaign. This was an exaggeration.

In the Bay of Biscay however the Anglo-American air offensive was soon to make the life of U-boats in transit almost unbearable. The rocket now fired from aircraft was so damaging that the enemy started sending the U-boats through in groups on the surface, fighting off the aircraft with gunfire in daylight. This desperate experiment was vain. In March and April 1943 twenty-seven U-boats were destroyed in the Atlantic alone, more than half by air attack.

In April 1943 we could see the balance turn. Two hundred and thirty-five U-boats, the greatest number the Germans ever achieved, were in action. But their crews were beginning to waver. They could never feel safe. Their attacks, even when conditions were favourable, were no longer pressed home, and during this month our shipping losses in the Atlantic fell by nearly three hundred thousand tons. In May alone forty U-boats perished in the Atlantic. The German Admiralty watched their charts with strained attention, and at the end of the month Admiral Doenitz recalled the remnants of his fleet from the North Atlantic to rest or to fight in less hazardous waters. By June 1943 the shipping losses fell to the lowest figure since the United States had entered the war. The convoys came through intact, and the Atlantic supply line was safe.

The struggle in these critical months is shown by the following figures:

ATLANTIC OCEAN

* * * * *

As the defeat of the U-boats affected all subsequent events, we must here carry the story forward. The air weapon had now at last begun to attain its full stature. No longer did the British and Americans think in terms of purely naval operations, or air operations over the sea, but only of one great maritime organisation in which the two Services and the two nations worked as a team, perceiving with increasing aptitude each other’s capabilities and limitations. Victory demanded skilful and determined leadership and the highest standard of training and technical efficiency in all ranks.

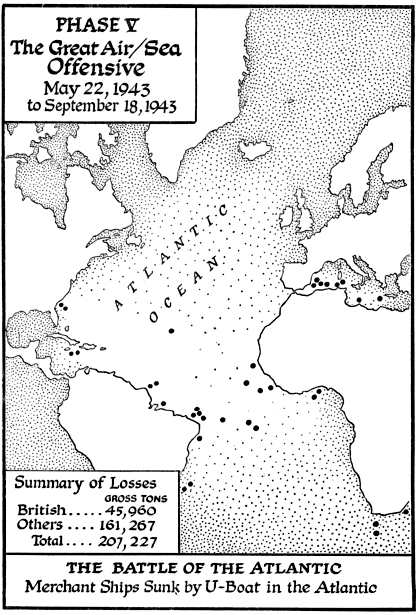

In June 1943 the beaten remnants of the U-boat fleet ceased to attack our North Atlantic convoys, and we gained a welcome respite. For a time the enemy’s activity was dispersed over the remote wastes of the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans, where our defences were relatively weak but where we presented fewer targets. Our air offensive in the approaches to the U-boat bases in the Bay of Biscay continued to gather strength. In July, thirty-seven of them were sunk, thirty-one by air attack, and of these nearly half were sunk in the Bay. In the last three months of 1943, fifty-three U-boats were destroyed in sinking only forty-seven merchant ships.

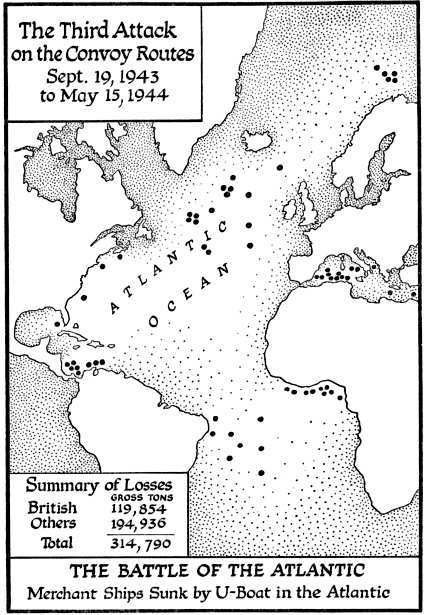

Throughout a stormy autumn the U-boats struggled vainly to regain the ascendancy in the North Atlantic. Our combined sea and air defence was by that time so strong that they suffered heavy losses for small results in every convoy battle. In anti-U-boat warfare the air weapon was now an equal partner with the surface ship. Our convoys were guarded by more numerous and formidable surface escorts than ever before, reinforced with escort carriers giving close and advanced air protection. More than this, we had the means to seek out and destroy the U-boats wherever we could find them. The combination of support groups of carriers and escort vessels, aided by long-range aircraft of the Coastal Command, which now included American squadrons, proved decisive. One such group commanded by Captain F. J. Walker, R.N., our most outstanding U-boat killer, was responsible for the destruction of six U-boats in a single cruise.

The so-called merchant aircraft-carrier, or M.A.C. ship, which came out at this time, was an entirely British conception. An ordinary cargo ship or tanker was fitted with a flying-deck for naval aircraft. While preserving its mercantile status and carrying cargo, it helped to defend the convoy in which it sailed. There were nineteen of these vessels in all, two wearing the Dutch flag, working in the North Atlantic. Together with the catapult-aircraft merchant ships (C.A.M.S.), which had preceded them with a rather different technique, they marked a new departure in naval warfare. The merchant ship had now taken the offensive against the enemy instead of merely defending itself when attacked. The line between the combatant and non-combatant ship, already indistinct, had almost vanished.