Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. (25 page)

Read Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. Online

Authors: Viv Albertine

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

1977–1978

The Slits go through managers very quickly. No one can control us. I don’t think a manager should control a band, ideally they should guide and facilitate, but control is what they seem to want to do. Also, when girls have an opinion, and the manager is a man, sexual politics rears its ugly head. They don’t hear,

We don’t want to play those kinds of venues, we’re trying to create a whole new experience, so even the venues we play have to be thought about carefully.

They hear,

I don’t want to fuck you.

They try and treat us like malleable objects to mould or fuck or make money out of.

It’s me who organises the band and liaises with the manager – if we have one – and it’s getting me down. Tessa and Palmolive are happy just to rehearse when they feel like it but I want to make this a great band, I wouldn’t bother with it if I didn’t see the potential. I’m sure it’s a bit of a bore for all of them, the way I’ve come steaming in full of ideas about clothes and hair and lyrics and image and rehearsals, but annoying as I am, there must be a part of them that wants that too, or they would’ve chucked me out by now.

Palmolive and Tessa are very close, they muck around together all the time, play-fighting, teasing, calling each other names, rolling around on the floor like a couple of lion cubs. I feel left out and boring. I can’t do that physical slapstick type of communicating. I feel stiff and awkward around them. Ari joins in occasionally, she’s younger so it’s not too difficult for her. Sometimes all three of them are rolling around on the floor and I stand there like a twit trying to laugh, trying to find it endearing and amusing. They must think I’m so uptight.

I get on well with Palmolive; of everyone in the band it’s Palmolive that I feel naturally closest to, in age and in thought. I think she’s interesting and wild and clever but although we occasionally have a good chat, she prefers to hang out with Tessa. Ari is making new friends of her own now, she inspires great loyalty and devotion and no doubt she feels liberated to be amongst people she hasn’t grown up in front of, that she can reinvent herself with.

When we go to Berlin I pick up on the decadence of the city and decide to try a new look on stage: Sid’s leather jacket open over a black bra. It’s very sexual. I feel brave, not sure if I can carry it off. The rest of the Slits hate it. They think it’s not right for the image of the band. I’m into feminist politics, always going on about it, and they don’t understand why I’m using such tired old iconography. But I like to use some of the old stuff, to invert it, or even, dare I say it, just to revel in the response. So I wear it anyway. That’s how I feel today. I feel sexual. I’m safe on stage to explore that stuff. It isn’t safe to do it on the streets of London, but I do it there too.

I’ve noticed English girls don’t show their sexuality, not like French and Italian girls do. We seem to be either ashamed of it or turn it into some sort of jokey, slapstick, seaside-postcard pantomime thing or a porny caricature. European women feel sexy their whole lives. Even older women behave like they’re sexually active and attractive. I’ve seen them do it since I was a child, when I used to visit France with my father. Older French women’s attractiveness isn’t taken away from them by society. In England we’re not supposed to relax into ourselves in any way – to enjoy the power of our sexuality. I remember when I was seventeen and I wore a child’s shrunken Mickey Mouse T-shirt to art school that showed my stomach – I was experimenting with crossing the boundaries between childhood and womanhood and also Disney was so unfashionable in this rarefied artistic environment, I thought it was funny and iconoclastic. A middle-aged male lecturer said to me, ‘Eugh! Who wants to look at your fat stomach? Put it away.’ I was seventeen, skinny. My stomach was as flat as a board. But he managed to make me doubt it. Is my stomach fat? Am I disgusting for showing it? Am I offensive? I never wore the T-shirt again.

I’m so exhausted one Saturday afternoon, I fall asleep on the sofa in Nora’s living room. The others have gone out, I’m too tired to go with them. I’ve become so wary of them all, so estranged, that I think to myself,

I mustn’t let them see me like this, so vulnerable, but it’ll be OK, I’m a light sleeper, I’ll wake up when I hear them come in the front door.

I’m worried they’ll see me asleep for fuck’s sake. Things have got that bad. I open my eyes and see Ari, Tessa and Nora staring down at me.

Oh no, I didn’t hear them.

I sit up quickly.

What horrible things are they going to say?

I brace myself. Ari says, ‘You looked so sweet lying there asleep. Your face looked so gentle and lovely.’ I can’t believe it. She’s utterly sincere. Ari is always sincere. She never lies.

The only time I feel I can safely express my vulnerability is when I’m with a boyfriend. Having a boyfriend is very important to me at the moment, it’s an emotional escape from the band. With a boy I can be soft and silly and funny. Mick’s on tour a lot, we write to each other but I know what he’s up to and he knows the same about me. Officially we’ve split up but we meet again when our mate Sebastian Conran invites a load of people to his parents’ house in Albany Street one night. Mick and I haven’t seen each other for months. It’s raining, I’ve got my red Vivienne Westwood boots on and I don’t want to get them wet. He picks me up and carries me across the road, splashing through the puddles in his blue suede Chelsea boots. It’s so romantic. Sebastian says we can stay in his parents’ bedroom tonight as they’re away. There’s a huge white bed, white walls, white carpet and a private bathroom. The next day Mick goes on tour with the Clash. A couple of weeks later I go on tour with the Slits. And that’s it, the end of Mick and Viv.

The Slits are on tour when Tessa’s father dies. She adored him. I have no idea what it feels like to lose a parent you love, how I would deal with it. Tessa shuts herself in a cubicle in the loos of a Top Rank we’re playing and refuses to come out – except to do the gig – or speak to anyone. She doesn’t want sympathy, she doesn’t want chats – all that sharing and caring nonsense. I realise she’s a very strong person in her own way.

Most of the time the Slits see me as bossy (they’re right). I wouldn’t stay with them if it weren’t for Ari; despite being so young, she has an obsessiveness, a drive, I don’t know where it comes from, it’s more than I ever had at fifteen. But Ari’s too young to organise things, I can’t expect any help from her in that department, so I have to do it. I book rehearsal rooms, ring around everyone in the band – or beg them to ring me if, like Tessa, they don’t have a phone – so I can tell them when the next rehearsal is. Palmolive is always late to rehearsals nowadays, sometimes she doesn’t turn up at all. I call her about getting together next week but she’s become enamoured with a guy called Tymon Dogg and his music – Tymon’s teaching her how to play tablas – compared to him she thinks the Slits are devoid of spirituality, she’s lost interest in us. I track Tessa down and tell her about the rehearsal. She can’t be bothered to come; it’s the last straw. I shut myself away in my tiny bedroom in Mum’s council flat in Highgate. I give up.

Ari phones me, Mum answers, I refuse to speak to her. I never want to see any of them again. Ari comes round to my home, no mean feat: I live right across the other side of London and she has no sense of direction, it will have taken her hours and many bus changes to find me. She knocks on the front door.

‘Viv, please talk to me.’

I ignore her. She knocks again.

‘I’m sorry, Viv. We do want to rehearse. Please open the door.’ It’s like we’re lovers, I’m upset, she’s begging forgiveness. Ari stays outside my door for a very long time pleading with me. With every knock my heart hardens. Even Mum takes pity on Ari and tells me to answer the door but I’m mad with grief and self-righteousness. I tell Ari to go away; eventually she does. I hate her. I hate them all. I’m deranged and defeated by their lack of commitment. And I’m ill.

I’ve been coughing for a year. Deep chesty coughing. I haven’t slept through a whole night for ten months. Mum’s given up trying to get me to go to the doctor. I have a permanent headache from the racking coughs, I can feel them right down in my diaphragm, right down in my pelvic floor.

For a whole year

.

I spend the night with Phil Rambow – an American singer I met through Rory – at Mick Ronson’s flat. Me and Phil don’t have sex, he can’t get near me, I cough and hack all through the night. In the morning I’m bathed in cold sweat with a red face and puffy eyes. I’m embarrassed. I must have kept everyone awake all night. No one says anything; I’m so grateful and impressed by Mick’s politeness as he offers me tea and toast. I see myself through his eyes: pale, spotty, ill, neglectful of my health. Unattractive. I go to the doctor. He says it’s serious and sends me to Brompton Chest Hospital. I lie in bed on a ward full of older women. Hospital is clean, white, restful. An oasis. No Sex clothes, just a nightie. No arguments, no goals, no decisions. I’m just a girl again. A week goes by. My face relaxes. After two weeks the colour returns to my cheeks and the coughing has subsided. I’m thinking more clearly. I decide I can’t be in the Slits any more, not as things are.

It will be devastating for me to leave them, but I’m not going to saddle myself with this situation any longer. Look where I’ve ended up for god’s sake. What I care about most is the music, but it’s not developing. I can’t bear the uncertainty every time we go out on stage, I never know if we’re going to make it through a song without it collapsing.

At the end of my second week in hospital I feel strong enough to call a meeting – Palmolive doesn’t come. Tessa and Ari gather round my bed, I lie propped up on a bank of pillows like a scene from

The Godfather

. I say I won’t go on as we are. I want to progress musically: to get tighter, not perfect, but enough to know we can get through a song and convey its meaning. I tell Ari and Tessa I need them to be behind the music and to have a more dedicated attitude to songwriting and rehearsing. If they can’t do that, I’m out. And lastly, I say, ‘I go, or Palmolive goes.’

Ari and Tessa take me seriously – maybe the surroundings help – I’ve never said anything like this before. I ask Tessa what she wants. I have no idea what she’ll answer, if she’ll answer. She says she agrees it’s time to buck up and Palmolive should go. Ari says the same.

I concentrate on getting well. My back is pummelled twice a day by physiotherapists, my lungs are drained of mucus every morning by nurses, I take inhalers, I sleep and I eat. The consultant tells me if I don’t give up smoking I will be dead within eighteen months. I give up smoking.

In just a few weeks I’ve started to forget who I used to be. Now I’m in this normal setting, talking to middle-aged women, housewives, I realise I’m not so different from them after all.

During my last week at the hospital, Mick strides in wearing his black leather jeans and leather jacket. He’s holding a bunch of flowers. I didn’t tell him I was here, he’s annoyed about that, but I don’t like people to see me when I’m ill. Ben Barson, who I fell in love with at Woodcraft, also visits me, bringing a pineapple. Two boys; that’s more like it. I feel more comfortable with Ben, he has no fear of illness. Mick’s squeamish about things like hospitals, germs and diseases.

When I leave hospital I’m very thin. I walk down the road with Ari and Tessa, just the three of us now. It feels weird without Palmolive, they say they’ve already told her she’s out, which I’m grateful for, it shows that they are taking responsibility. Together we hatch a plan – we’re going to get a new drummer, we’re going to record our album, it’s going to be on our favourite label, Island Records (they haven’t approached us yet, but we’ll convince them they want us) – and it’s going to be brilliant, a classic.

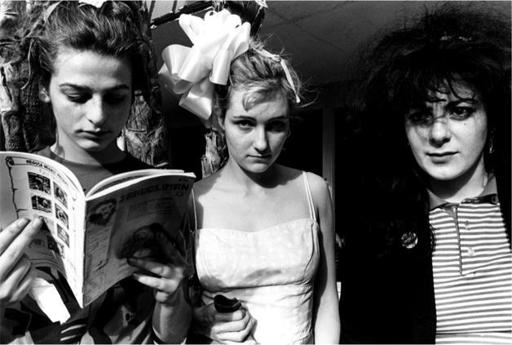

With Ari and Tessa at the Tropicana Hotel in LA, wearing a vintage dress and giant paper bow from a bouquet of flowers in my hair

52 SONGWRITING

1977–1979

We love Dionne Warwick’s record

Golden Hits Volume 1

, where she sings loads of Bacharach and David songs. We own it collectively; I can’t remember how we came across it, probably at the Record and Tape Exchange in Notting Hill. We’ve pulled the record apart, listened to every instrument, the drum patterns, the backing vocals, the very understated

chk chk chk

guitar sound, which mostly plays on the off beat.

I wonder if reggae was influenced by this sort of music? I heard American ‘crooning’ was big in Jamaica and influenced lovers’ rock, so maybe it was.