Cod (13 page)

Authors: Mark Kurlansky

Handlining. The Georges Bank cod fishery, plate 32 from

The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the U.S.

by George Brown Goode, 1887. (Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts)

The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the U.S.

by George Brown Goode, 1887. (Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts)

Â

In 1861, it was written in the

Journals of the Assembly

in Nova Scotia, “Setline fishing, there can be little doubt, was induced by the enormous bounty of ten francs paid by the French government for every quintal [sixty-five fish] of fish caught by their fishermen.... The writer has been informed, incredible as it may appear, that some of these lines have as many as ten thousand hooks fastened to them.” Such an operation required only a few dozen men and five dories.

Journals of the Assembly

in Nova Scotia, “Setline fishing, there can be little doubt, was induced by the enormous bounty of ten francs paid by the French government for every quintal [sixty-five fish] of fish caught by their fishermen.... The writer has been informed, incredible as it may appear, that some of these lines have as many as ten thousand hooks fastened to them.” Such an operation required only a few dozen men and five dories.

As the nineteenth-century debate over longlining grew, nationalism, more than conservation, seems to have been the issue. Unfair competition from the French subsidy system angered British North America, later Canada, more than the possibility of overfishing from the technique it financed.

Distrust of new fishing techniques is endemic to fishing. Longlining had always been controversial in Iceland, as was netting when it was first used for cod in Icelandic waters in 1780. But fishermen objected to netting because they feared it would block off the fish and they would move to some other waters. The principal Scandinavian objection to longlining was that it was unfair, undemocratic. Longlining required capital to buy large quantities of bait, and those who could not afford the bait did not have the opportunity. In North America, the principal nineteenth-century argument against longlining was the same one brought up in Petty Harbour when it banned the practice in the late 1940s. As Kipling described in his novel, there were too many fishermen out on the Banks working the same grounds. If they all started using longlines, there would not be enough space and they would be constantly fouling each other's lines.

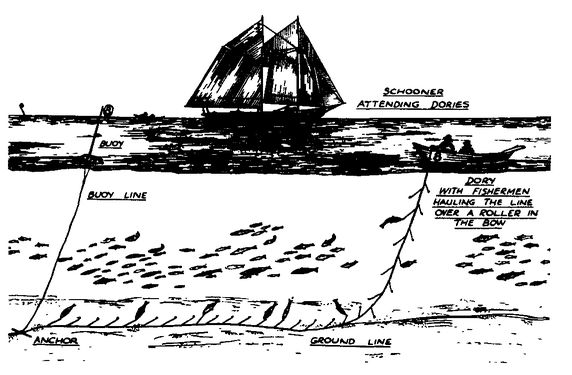

Trawl-line dory fishing (longlining), figure 4 from

Fisheries and Fishing Vessels of the Canadian Atlantic

by N. J. Thompson and J. A. Marsters. (Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts)

Fisheries and Fishing Vessels of the Canadian Atlantic

by N. J. Thompson and J. A. Marsters. (Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts)

Â

There was the rare, purely conservationist measure such as Newfoundland's 1858 law regulating the mesh size in the herring fishery. But it was difficult to think of overfishing when the catches were getting bigger every year. Catches were improving not because the stocks were plentiful but because fishing was getting more efficient. Nevertheless, as long as better fishing techniques yielded bigger catches, it did not seem that the stocks were being depleted.

The indomitable force of nature was a fashionable nineteenth-century belief. The age was marked by tremendous optimism about science. The lesson gleaned from Charles Darwin, especially as interpreted by the tremendously influential British scientific philosopher Thomas Henry Huxley, was that nature was a marvelous and determined force that held the inevitable solutions to all of life's problems. Huxley was appointed to three British fishing commissions. He played a major role in an 1862 commission, which was to examine a complaint of driftnet herring fishermen, who said that longliners were responsible for their diminishing catches. The fishermen had asked for legislation restricting longlining. But Huxley's commission declared such complaints to be unscientific and prejudicial to more “productive modes of industry.” The commission also established the tradition in government of ignoring the observations of fishermen. It reported that “fishermen, as a class, are exceedingly unobservant of anything about fish which is not absolutely forced upon them by their daily avocations.”

At the 1883 International Fisheries Exhibition in London, which was attended by most of the great fishing nations of the world, Huxley delivered an address explaining why overfishing was an unscientific and erroneous fear: “Any tendency to over-fishing will meet with its natural check in the diminution of the supply, ... this check will always come into operation long before anything like permanent exhaustion has occurred.”

Considering the international impact of Huxley's work in the three commissions, it is disturbing to note that he once explained his participation in these paid appointments by saying, “A man with half a dozen children always wants all the money he can lay hands on.”

For the next 100 years, Huxley's influence would be reflected in Canadian government policy. An 1885 report by L. Z. Joncas in the Canadian Ministry of Agriculture stated:

The question here arises: Would not the Canadian fisheries soon be exhausted if they were worked on a much larger scale and would it be wise to sink a larger amount of capital in their improvement?

... As to those fishes which, like cod, mackerel, herring, etc. are the most important of our sea fishes, which form the largest quota of our fish exports and are generally called commercial fishesâwith going so far as to pretend that protection would be useless to themâI say it is impossible, not merely to exhaust them, but even noticeably to lessen their number by the means now used for their capture, especially if, protecting them during their spawning season, we are contented to fish them from their feeding grounds. For the last three hundred years fishing has gone on in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and along the coast of our Maritime Provinces, and although enormous quantities of fish have been caught, there are no indications of exhaustion.

Joncas supported this assertion by referring to a British Royal Commission in which Huxley participated: “Not withstanding the enormous and continually increasing quantities of fish caught annually along the coasts of Great Britain, the English fisheries show no sign of exhaustion.”

But Joncas had a political agenda for making these assertions. He believed that the Canadian government, like that of France, should become more involved in financially supporting its fishing industry. In the decades since the French had introduced longlining, the technique had become widely used in Canadian fisheries. Joncas now argued in favor of gillnetting because it did not require the great quantity of bait needed for longlining. He pointed out that gillnetting was being used by Canada's biggest competitor in the world cod market, Norway.

A gill net is a net anchored slightly above the ocean floor. It looks somewhat like a badminton net. Groundfish become caught in it and, trying to force their way through headfirst, end up being strangled at the gills. The nets are marked by buoys, and the fisherman has only to haul them up every day and remove the fish. But sometimes the nets detach from their moorings. As they drift around the ocean, they continue to catch fish until they become so weighted down that they sink to the ocean floor, where various creatures feast on the catch. When enough has been eaten, the net begins to float again, and the process continues, helped by the fact that, in the twentieth century, the gill net became almost invisible when hemp twine was replaced first by nylon and then by monofilament. Since monofilament is fairly indestructible, it is estimated that a modern “ghost net” may continue to fish on its own for as long as five years.

Joncas complained that the twenty- to thirty-foot schooners used in the Gaspé and the Prince Edward Islands were far too small to be competitive, and he recommended that the government help Canadian fishermen acquire large ships with deck space for onboard fish processingâwhat would one day be called “a factory ship.”

The solution to Joncas's quest already existed. In midcentury, the steam engine had been invented, but fisheries were slow to seize on this machine. When they did, it would be the first new idea to dramatically change cod fishing since the discovery of North America. Soon there would be another idea: frozen food. Once these two inventions were put together, the entire nature of commercial fishing would change.

MR. LEOPOLD BLOOM ATE WITH RELISH THE INNER ORGANS OF BEASTS AND FOWLS. HE LIKED THICK GIB-LET SOUP, NUTTY GIZZARDS, A STUFFED ROAST HEART, LIVER SLICES FRIED WITH CRUSTCRUMBS, FRIED HENCOD' S ROE.

âJames Joyce,

Ulysses,

1922

Ulysses,

1922

Â

Leopold Bloom's tastes were more old-fashioned than eccentric. Until recently, cod roe was the central feature of an Irish breakfast. Most Irish today do not eat cod roe for breakfast because, though they do not seem to realize it, what is called Irish breakfast is increasingly similar to English breakfast. In the old Irish breakfast, the roe was sliced in half and fried in bacon fat or simply boiled.

BOILED ROE

It is better to buy roe raw and cook it yourself. Do not choose too large a roe; the smaller ones have a more delicate flavour.

Wrap the roe in a piece of cheesecloth and put it into a warmed salted water. Let it cook very gentlyâthe water should just bubble and no moreâfor at least 30 minutes. When cooked, take it out and let it get cold. The outer membrane is taken off before using, but leave it on until you use the roe, as it keeps it moist.

âTheodora FitzGibbon,

A Taste of Ireland,

1968

A Taste of Ireland,

1968

Also see pages 247-49.

8: The Last Two Ideas

SAID HE, “UPON THIS DAINTY COD

HOW BRAVELY I SHALL SUP,Ӊ

WHEN WHITER THAN THE TABLECLOTH,

A GHOST CAME RISING UP!

HOW BRAVELY I SHALL SUP,Ӊ

WHEN WHITER THAN THE TABLECLOTH,

A GHOST CAME RISING UP!

âThomas Hood (1799-1845), “The Supper Superstition”

I

f a cod fisherman of Cabot's day could have returned to work in the year 1900, he would have been dazzled by the new inventions on shore, but once he went to sea his job would have seemed familiar. When John Cabot's voyage opened up North American waters to Europeans, the nature of cod fishing changed dramatically. Fishermen then pursued cod in much the same way for the next four centuries. True, navigation improved in the seventeenth century. The chronometer made it possible to fix a longitude in the eighteenth century. The three-masted bark with its dories was developed. New Englanders invented the schooner. Telegraph and then the trans-Atlantic cable made it possible for long-distance fleets to get news of market price trends and storm warnings. But by the beginning of the twentieth century, these inventions had only slightly changed the job of the fisherman and his ability to catch fish. Fishermen were still working the same grounds with only minor variations on the same types of gear, still in sail-powered vesselsâIcelanders were still using oarsâand it was still a dangerous and arduous job.

f a cod fisherman of Cabot's day could have returned to work in the year 1900, he would have been dazzled by the new inventions on shore, but once he went to sea his job would have seemed familiar. When John Cabot's voyage opened up North American waters to Europeans, the nature of cod fishing changed dramatically. Fishermen then pursued cod in much the same way for the next four centuries. True, navigation improved in the seventeenth century. The chronometer made it possible to fix a longitude in the eighteenth century. The three-masted bark with its dories was developed. New Englanders invented the schooner. Telegraph and then the trans-Atlantic cable made it possible for long-distance fleets to get news of market price trends and storm warnings. But by the beginning of the twentieth century, these inventions had only slightly changed the job of the fisherman and his ability to catch fish. Fishermen were still working the same grounds with only minor variations on the same types of gear, still in sail-powered vesselsâIcelanders were still using oarsâand it was still a dangerous and arduous job.

Well into the twentieth century, Lunenburg, Nova Scotia's, Grand Banks fleet stayed with sail power. “The Lunenburg cure,” heavily salted on the schooners and then dried on flakes along the rocky sheltered coastline, was traded in the Caribbean. The town of Lunenburg was built on a hill running down to a sheltered harbor. On one of the upper streets stands a Presbyterian church with a huge gilded cod on its weather vane. Along the waterfront, the wooden-shingled houses are brick red, a color that originally came from mixing clay with cod-liver oil to protect the wood against the salt of the waterfront. It is the look of Nova Scotiaâbrick red wood, dark green pine, charcoal sea.

The Lunenburg fishery was famous for its schooners and its role in a series of Canadian-U.S. schooner races between 1886 and 1907. Then, in 1920, when the America's Cup race was canceled because of high seas, a publisher of the

Halifax Herald and Mail

who thought these sportsmen fainthearted put up a $5,000 prize and a silver cup for a fishermen's schooner race between Lunenburg and Gloucester. Fishermen, he insisted, knew how to sail schooners in rough weather. The

Gloucester Daily Times

accepted the challenge. Gorton's, the Gloucester seafood company, sponsored a schooner that beat Lunenburg's schooner twice. Then, in 1921, Lunenburg built a bigger schooner, the

Bluenose.

The competition continued until 1938, and though Gloucestermen won several races, they never took the cup away from the

Bluenose,

which can now be seen on the Canadian dime, matchbooks, and almost anywhere else eyes might fall in Maritime Canada.

Halifax Herald and Mail

who thought these sportsmen fainthearted put up a $5,000 prize and a silver cup for a fishermen's schooner race between Lunenburg and Gloucester. Fishermen, he insisted, knew how to sail schooners in rough weather. The

Gloucester Daily Times

accepted the challenge. Gorton's, the Gloucester seafood company, sponsored a schooner that beat Lunenburg's schooner twice. Then, in 1921, Lunenburg built a bigger schooner, the

Bluenose.

The competition continued until 1938, and though Gloucestermen won several races, they never took the cup away from the

Bluenose,

which can now be seen on the Canadian dime, matchbooks, and almost anywhere else eyes might fall in Maritime Canada.

Other books

Being With the Brothers Next Door by Jenika Snow

Mind Hacks™: Tips & Tools for Using Your Brain by Tom Stafford, Matt Webb

Ties That Bind by Heather Huffman

Against the Wall by Julie Prestsater

Private Pleasures by Bertrice Small

Feather Woman of the Jungle by Amos Tutuola

Haunted Love by Cynthia Leitich Smith

Grave Sight by Charlaine Harris

Senescence (Jezebel's Ladder Book 5) by Scott Rhine