Collected Essays (9 page)

Authors: Rudy Rucker

Now the burning slugs turned on their tormentors, engulfing them like psychedelic kamikaze napalm. There was great screaming from the victims, screams that were weirdly, hideously ecstatic. And then the mob’s few survivors had fled, and the rest of the slugs had wormed off into the flickering night. Willy and Ulam split the scene as well.

Cyberpunk lives!

Note on “Cyberpunk Lives”

Written 1998.

Appeared as “Letters From Home” in

The New York Review of Science Fiction

, #113, January 1998.

Although it’s framed as a review of three books, the essay also has some of my thoughts on the similarities between the cyberpunks and the Beats. I particularly like the idea that I get to be Burroughs. And I mention the meeting with Ginsberg that I describe in my “William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg” essay—one of the high points of my life.

The Freestyle Antifesto (Written with Marc Laidlaw)

Write like yourself. Exaggerate it. Write

more

like yourself. You are correct. Write more. Only you have the secret. Tell every detail in the readiest tongue. Write like yourself except more so. Everyone but you is crazy. Write high, write drunk, write depressed, write in ecstasy, always tell the truth and always lie. Manipulate subtext; transreally seize each character and attitude from that day’s mental magpie-gleanings. Your streetscene events are, ideally, to be elicited by you in the manner of a ranter who leaves no soul unturned—and no idler in your room’s corner is left unharrassed or unloved or untreated to a freestyle soul-winning session.

I view Marc Laidlaw as the head freestylist, the behind-it-all zealot surfpunk dictator of freestyle. Marc is the author of that most immaculate novel,

Dad’s Nuke

, where timebake flurries snatch your ass from the diaper into the deathbed. On deck: Marc’s Tibetan Buddhist SF novel,

The Neon Lotus

, with the future fantasia

Kalifornia

still to come.

Marc and I picked up on the word

freestyle

while working on our surfing SF story, “Probability Pipeline.” To me, surfing has always been a central life image, as in the phrase, “wave with it.” Now that I’m in California, I got a wetsuit and used board from local shop. By way of further research, I went out to try surfing at Three Mile Beach north of Santa Cruz on New Year’s Day, 1987, with my wife Sylvia, Marc, his wife Geraldine, and our three kids. Memorable.

By way of introducing Marc’s quintessential summation of freestyle writing, he sent me an ad torn from the pages a surfing magazine, with the following block of copy circled:

Break down the word “freestyle” and you have two of the most liberating concepts in life. Given such a forum of experimentation and challenge as the Ocean, freestyle becomes a statement limited only by the participant’s mind…Adventurism represents the cutting edge of the freestylist. It requires an individual who is willing to take any risk at any time, subject himself to the demands of the sea, and ignore limitations imposed on him by friends, society, or the conditions…Freestyle is a forum of inner rhythm: what beat do you choose to march to? In all likelihood, that beat, that inner rhythm, projects into our style of living and surfing, and draws our life experiences to us…Each person’s moves and personality blend together to create style. Each person’s style is different. [From an ad in

Breakout

magazine, December 1986.]

This ad-copy itself serves as a synchronistic Rosetta stone for the meaning of freestyle. As Marc explicates:

There it is, Rude Dude. The freestyle antifesto. No need to break down the metaphors—an adventurist knows what the Ocean really is. No need to feature matte-black mirrorshades or other emblems of our freestyle culture—hey, dude, we know who we are. No need to either glorify or castrate technology. Nature is the Ultimate. We’re skimming the cell-sea, cresting the waves that leap out over the black abyss of the maybe-death/whatever-that-is. Wet dreams of geometry: the curl of the wave as we carve our turns toward the blue lip, glossing over the shoulder into the turquoise pocket of ecstasy.

Yeah, baby. Write like yourself.

Note on “The Freestyle Antifesto”

Written 1987.

Based on Marc Laidlaw’s zine,

Freestyle SF

, Fall 1987.

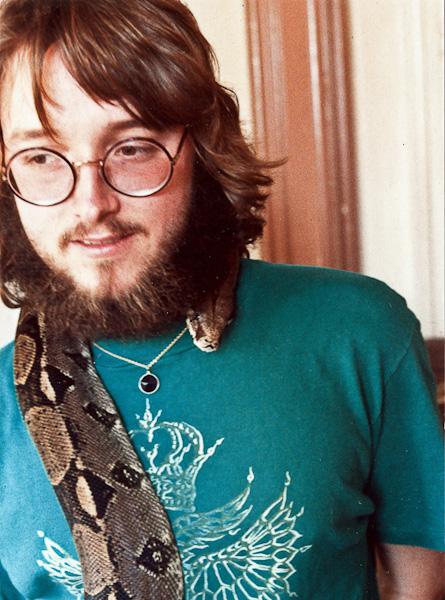

Marc Laidlaw in 1986

Marc and I ended up publishing four surfing SF stories, “Probability Pipeline,” “Chaos Surfari,” “The Andy Warhol Sand Candle,” and “The Perfect Wave.” You can find these tales in my

Complete Stories

(Transreal Books, 2012).

Marc and I tried to convince our fellow Bay Area SF-writers Richard Kadrey, Pat Murphy, and Michael Blumlein that they were freestylists too, but none of them took our wild talk seriously. The problem with freestyle, as a movement, was that it really had no prescriptive program. We were all diverging along our own worldlines.

One more great quote from Marc. We weren’t having an easy time getting our far-out stories and novels published, and he remarked, “The editors will sink into the tarpits like dinousaurs. With their throats ripped out by a saber-toothed tiger. And I, Rudy,

I will be that tiger

.”

In the end, we may not have ripped out anyone’s throats, but Marc got a great job writing the stories for games like

Half-Life

at the computer-gaming company Valve Software. And he’s still writing a gem-like story now and then. And me? I’m starting in on self-publishing ebooks! Forever freestyle.

What SF Writers Want

I think some of the appeal of SF comes from its association with the old idea of the Magic Wish. Any number of fairy tales deal with a hero (humble woodcutter, poor fisherman, disinherited princess) who gets into a situation where he or she is free to ask for any wish at all, with assurance that the wish will be granted. Reading such a tale, the reader inevitably wonders, “What would

I

wish for?” It’s pleasant to fantasize about having such great power; and thinking about this also provides an interesting projective psychological test.

Some SF stories hinge on the traditional Magic Wish situation—the appearance of a machine (= magic object) or an alien (= magic being) who will grant the main character’s wishes. But more often, the story takes place

after

the wish has been made…by whom? By the author.

What I mean here is that, in writing a book, an SF writer is in a position of being able to get any Magic Wish desired. If you want time travel in your book…no problem. If you want flying, telepathy, size-change, etc., then you, as SF writer, can have it—not in the real world, of course, but in the artificial, written world into which you project your thoughts.

To make my point quite clear, let me recall a conversation I once had with a friend in Lynchburg. “Wouldn’t it be great,” my friend was saying, “if there were a machine that could bring into existence any universe you wanted, with any kinds of special powers. A machine that could call up your favorite universe, and then send you there.” “There is such a machine,” I answered. “It’s called a typewriter.”

Okay. So the point I want to start from here is the notion that, in creating a novelistic work, the writer is basically in a position of being able to have any wish whatsoever granted.

What kinds of things do we, as SF writers, tend to wish for? What sorts of possibilities seem so attractive to us that we are willing to spend the months necessary to bring them into the pseudoreality of a polished book? What kinds of needs underlie the wishes we make?

In discussing this, my basic assumption is that the driving force behind our SF wishes is a desire to find a situation wherein one might happy…whatever “happy” might mean for any particular writer.

There are, of course, a variety of very ordinary ways to wish for happiness: wealth, sexual attractiveness, political power, athletic prowess, sophistication, etc. I’m not going to be too interested in these types of wishes here—because such wishes are not peculiar to the artform of SF. Any number of standard paperback wish-fulfillments deal with characters whom the author has wished into such lower-chakra delights.

No, the kind of wishes I want to think about here are the weird ones—wishes that have essentially no chance of coming true—wishes that are really worth asking for.

I can think of four major categories of SF wishes, each with several subcategories. Just to make this seem highly scientific, I'll assign subcategory numbers.

Travel

. This includes:Space travel.Time travel. Changing size scale. Travel to other universes.

Psychic powers

. Which comprises: Telepathy. Telekinesis.

Self-change

. This means: Immortality. Intelligence increase. Shape shifting.

Aliens

. Two kinds: Robots. Saucer aliens.

Let’s look at these notions one at a time.

Travel

Your position relative to the world can perhaps be specified in terms of four basic parameters:

space-location

,

time-location

, your

size scale

, and

which universe

you’re actually in. Our powers to alter these parameters are very limited. Although it is possible to change space-location, this is hard and slow work. We travel in time, but only in one direction, and only at one fixed speed. In the course of a lifetime, our size changes, but only to a small extent. And jumping back and forth among parallel universes is a power no one even pretends to have. Let’s say a bit about the ways in which science fiction undertakes to alter each of these four stubborn parameters.

Space travel

. Faster-than-light drives, matter transmission, and teleportation are all devices designed to annihilate the obdurate distances of space. One might almost say that these kind of hyper-jumping devices turn space into time. You no longer worry about how far something is, you just ask when you should show up.

Would happiness finally be mine if I could break the fetters of space? I visualize a kind of push-button phone-dial set into my car’s dashboard, and imagine that by punching in the right sequence of digits I can get

anywhere

. (Actually, the very first SF story I ever read was a Little Golden Book called

The Magic Bus

. I read it in the second grade. The Bus had just one special button on the dash, and each push on the button would take the happily tripping crew to a new

randomly selected

locale. Of course—ah, if only it were still so easy—everyone got home to Mom in time for supper and bed.) That would be fun, but would it be enough? And what is enough, anyway?

In terms of the Earth, power over space is already, in a weak sense, ours. If it matters enough to you, you can actually travel anywhere on Earth—it’s not instantaneous, using cars and planes, but you do get there in a few days. Even easier, by using a telephone, you can actually project part of yourself (ears and voice) to any place where there’s someone to talk to. But these weak forms of Earth-bound space travel are the domain of travel writing and investigative journalism, not of SF.

Hyperjumping across space would be especially useful for travel to other planetary civilizations. One underlying appeal in changing planets would be the ability to totally skip out on all of one’s immediate problems, the ability to get out of a bad situation. “Color me gone,” as some soldiers reportedly said, getting on the plane that would take them away from Viet Nam and back to the U.S. “I’m out of here, man, I’m going back to the

world

.” Jumping to a far-distant planet would involve an escape from real life, and certainly SF is, to some extent, a literature of escape.

Time travel

. I once asked Robert Silverberg why time travel has fascinated him so much over the years. He said that he felt the desire to go back and make good all of one’s major life-errors and past mistakes. I tend to look at this a little more positively—I think a good reason for wanting to go back to the past is the desire to re-experience the happy times that one has had. The recovery of lost youth, the revisiting of dead loved ones.

A desire to time travel to an era before one’s birth probably comes out of a different set of needs than does a desire to travel back to earlier stages of one’s own life. People often talk about the paradoxes involved in going back to kill their ancestors—this gets into the territory of parricide and matricide. And a sublimated desire for suicide informs the tales about directly killing one’s past self. Other time travel stories talk about going back to watch one’s parents meeting—I would imagine that this desire has something to do with the old Freudian concept of witnessing the “primal scene.”

What about time travel to the future? This comes, I would hazard, out of a desire for immortality. To

still be here

, long after your chronological death.