Color: A Natural History of the Palette (25 page)

Read Color: A Natural History of the Palette Online

Authors: Victoria Finlay

Tags: #History, #General, #Art, #Color Theory, #Crafts & Hobbies, #Nonfiction

This man was also going to help to make a new world. But, rather like Columbus, on that warm day in 1492 Juan Leonardo didn’t have any idea of whether he was travelling to death or to discovery. In fact, as it would turn out, the Italian’s voyage would lead to Spain’s secret red, and the Jew’s would lead eventually to a mysterious orange.

CREMONA

The guidebooks had been rude about Cremona. “Nice but boring” was the general opinion. It was neither as exciting as Milan to the west, nor as picturesque as anything around the lakes to the north. But I was heading to this small town in northern Italy on a mission. “Dance the orange,” the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke had written, in a wonderful waltzing poem about a fruit and a color that pretend to be sweet but are actually rather rambunctious and challenging. And I remembered the words—I almost sang them to myself—as I drove into Cremona on a warm day in August, to find out how one particular orange can—perhaps— make musical instruments sing. Some of the greatest instruments in the world came from Cremona, and yet the composition of the varnishes that make them shine almost as sweetly as they play is still a mystery. In around 1750 the secret of how Antonio Stradivari made his orange varnish was lost; and to this day nobody knows what he put in it. Instrument-makers have been trying to find the recipe for years: for some the search has become an obsession. It is almost as if they believed that once they had the secret of the instrument’s skin, they would be able to find the mystery of its soul— and there would be nothing stopping them from making something very much like a Stradivarius

1

for themselves. Some have even whimsically suggested that the best violins are so full of life and tragedy that they may have been painted with blood.

2

However, dried blood is more brown than orange, and it is probably better as a metaphor than as a material.

Cremona is on the banks of the River Po. At one point the city was big enough to be an enemy of Milan; today it is just one of its many commuter satellite towns. Yet there is something charming about the place—its slightly run-down condition and general sense of surprise at the arrival of visitors give it a sense of authenticity. The heart of the city is the Plaza del Commune next to the thirteenth-century cathedral, and as I sat there on my first morning drinking lattes in the sunshine I saw a man riding past. Strapped to his back was a black viola case. He swung off his bicycle and marched into a shop. Later I peeked through the window of what turned out to be a violin workshop, and I could see him deep in discussion with a middle-aged man. The owner of the instrument was emotional—there was clearly something wrong with the bridge—and the craftsman was trying to placate him. It struck me as a quintessentially Italian moment, and certainly a scene that has been played out numerous times in this city. For this is the place where the three biggest names in violin history were based: Stradivari, Guarneri and the whole Amati family. It is a place where people have cared passionately about violins.

And marvellously some people still care. Today, if you walk along certain streets, you can still catch the pine scents of turpentine floating on the breeze, and see shop after shop of craftspeople working with delicate slices of maple. “But why Cremona?” was my question. “What’s so special about this city that it has nurtured such talent?” “I don’t know,” answered the woman at the tourist office. “Because we are lucky?” she suggested.

Cremona has not always thought itself particularly lucky to have this tradition; in fact for years it didn’t seem to care at all. By the late nineteenth century violins had been largely forgotten: like Stradivari’s varnish, the knowledge had been almost completely lost. And then a fascist dictator stepped in. Perhaps it was one of the few good things he did in his life, and his motives were certainly dubiously nationalistic ones, but in 1937 Benito Mussolini started a school for violin-making—and opened a music museum to celebrate the city’s past.

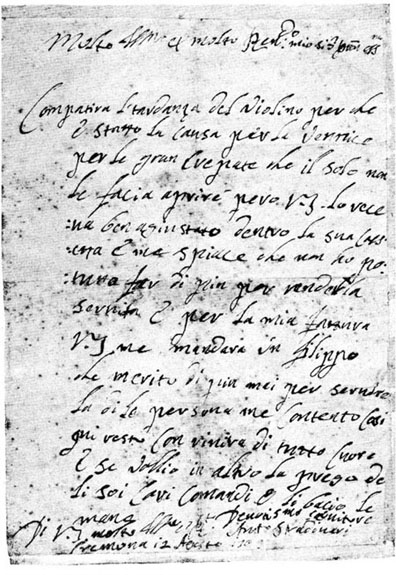

The Stradivari Museum in Cremona was built at speed, and it shows. With its dry displays of old carpentry tools scattered between bits of instruments (none of them Strads) it must qualify as one of the most boring museums about an interesting subject in the whole of Europe. It houses the unique forms that the master used to make his instruments, but there is little effort to explain them to a non-expert. However, there was one item that for me at least was worth the entrance fee: a letter, in Stradivari’s own hand, talking about the varnish. “Most illustrious, most reverend and worthy Patron,” he had written on August 12, 1708. “I beg you will forgive the delay with the violins occasioned by the varnishing of the large cracks, that the sun may not re-open them.” The handwriting is of a man who was an artisan rather than a scholar; he even, charmingly, decorated his Fs and the tails of the Ps, with curls that are reminiscent of the curved F-hole on the front of every violin. Stradivari’s letter ends with his deliciously cheeky bill: “For my work, please send me a filippo, it is worth more, but for the pleasure of serving you I am satisfied with this sum.”

That sentence about the “varnishing of the large cracks” has been examined and unravelled numerous times over the intervening centuries to see what clues it might reveal about the secret of Stradivari—and of the Amatis before him. The varnish must have been very soft for it to take so long to dry. Was the sun-drying part of the secret? people have wondered. And was Stradivari’s recipe similar to that of Jan van Eyck, who used to put his altarpieces outside to dry in the sunshine—and once left one out so long that the whole painting split apart?

3

Stradivari’s “varnish” letter

A student was manning the museum’s front desk. “Why Cremona?” I asked him. He shrugged and said he didn’t know. But he passed me an expensive color book in English about the history of the violin. I flicked through it and suddenly a single paragraph caught my eye. It explained how the instrument-making tradition started in 1499 when a man called Giovanni Leonardo da Martinengo arrived in town. He was a lute-maker and a Sephardic Jew, and many years later he would teach his art to two brothers: Andrea and Giovanni Antonio Amati. In the 1550s Andrea would make some of the first violins, after a musician in nearby Brescia decided to take a bow to the lute-guitar and play it like an Arabic

rebab

rather than plucking it. And two generations later, Andrea’s grandson Niccolo would teach this new craft to both Stradivari and Andrea Guarneri.

This might, I realized, be the answer to my question. Perhaps it all started in Cremona because one day a man turned up at the gates of the city, a man who had such knowledge that when he passed on his skills to two talented boys they became geniuses. He must also have had a rare knowledge of varnish: nobody knows where the recipe came from, but the Amatis must have learned it from someone, as it is there in their earliest pieces.

4

We know almost nothing about this lute-maker except the year he arrived, the fact that he must have been one of the thousands of Jews expelled from Spain in 1492, and that by the time of a census in 1526 he had the two Amatis (Andrea would have been twenty-one by then) working in his shop. We don’t even know his real name: Martinengo is a town in Austrian Italy where he may have lived for a while, Leonardo could have been his baptismal name—if he had been one of the thousands of Spanish Jews who turned Christian

5

— and Giovanni is an Italian version of Juan. So our luthier’s name was itself a collection of stories. He was a composite man—made up of many different parts, rather like one of his own lutes.

I think of him that first day in Cremona not as a man exhausted after a long journey, but as a storyteller walking proudly along the Via Brescia toward the center of town, surely attracting the attention of local urchins, who would be fascinated by the strange deep-bellied beast that he carried and which they would have pestered him to play. And perhaps he would have sat down and strummed them a ballad. Not for too long: like many instrument-makers he would probably never have thought of himself as a musician; but also he may not have wanted to think too much about the home he had lost. It would hurt too much.

What could this man have seen in those seven years? Had the terrible times won out, or had the experience of journeying through Europe just as the Renaissance was starting brought him and his art alive? Either way, something happened, because the skills taught by this refugee to those two Italian boys had not been taught before. Half the Jews in Spain went to Portugal. I hope for Martinengo’s sake he wasn’t one of them. A wealthy man had paid a ducat a head to the King of Portugal, which bought him and half his countrymen the right to stay for six months. After their time was up, the Portuguese treated them as cruelly as the Spanish, and the lucky ones left. It was their second sad exodus in a year.

Our luthier would have eventually headed east through the Mediterranean, and as he travelled he would have inevitably collected objects and colors and experiences that would be useful to him later. I imagine he was a creative, experimental and individualistic man. And he was certainly moving inexorably into the kind of world that valued exactly those qualities. Today there is a desire among some artists to rediscover the methods of the past—hence the interest in Stradivari’s orange varnish. But this search for something “authentic” is nothing new; art history is so full of nostalgia that to some extent it has been shaped by it. The search for lost knowledge has been a driving force in many art movements. The Victorians created neo-Gothic, but the creators of what was called Gothic were simply harking back to an imagined time in the Dark Ages. Even Roman style was neo-Greek.

And in the same way it was almost by chance that the end of the fifteenth century was a time of discovery. Because for the people actually living through it, it would have seemed more like a time of rediscovery. Artists and architects were busy trying to regain the spirit of Ancient Rome, while priests were trying to recapture the sense of wonder in the early Church. Even navigators were trying to rediscover rather than discover: Columbus’s original brief was not to find new land, but to investigate an alternative trading route to Asia. So a brilliant young artisan travelling through the Mediterranean would, in the spirit of his time, have been fascinated by the wealth of old materials. And he could well have sampled them all—the woods, the pigments, the oils and the varnishes—in an attempt to try to re-create the best instruments from the past: the Stradivaris of his own time.

BASTARD SAFFRON AND THE BLOOD OF DRAGONS

Jews were more welcome in Muslim North Africa than in Catholic France. So Martinengo’s first stops would probably have been the southern ports—Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli. And in the covered bazaars of those cities this Renaissance refugee would have found the first of many potential coloring ingredients for his portable studio: an orange flower, rather like a marigold.

Safflower is unusual: if you add alkalis to the dye broth it is yellow; with acids it goes a beautiful crimson pink which is the color of the original “red” tape once tied around legal documents in England and now gives its name to any bureaucratic knotty procedures. It would have been known to traders in the busy North African bazaars for more generations than anyone could count: Ancient Egyptians used it to dye mummy wrappings and to turn their ceremonial ointments an oily orange. They valued it so much that they put garlands of safflowers entwined with willow leaves in their relatives’ tombs, to comfort them after death.

It is also a plant to be wary of. Throughout its five thousand years of cultivation, safflower pickers have been easily spotted going to work in the fields—they have been the ones with leather chaps from thigh to boot to protect them from its spines. Today, if safflower stems get into the throat of a combine harvester, it is almost impossible to get them out. “Burn the combine” is the joke solution.

6

And an American safflower producer in the 1940s had a favorite story of a dog he saw chasing a rabbit: just when it seemed to be caught the rabbit dashed into a safflower field. The dog followed, but a few seconds later was seen sheepishly backing out, one paw at a time.

For buyers of colors, safflower is a dye to be careful of too, especially if you are not looking for it. This plant has been switched so often for another more expensive yellow dye that one of its names is “bastard saffron.” And indeed nobody is actually sure of its parentage—whether it first came from India or North Africa. It is celebrated in both places, and in India and Nepal it has been a holy color, perhaps because it is close to the color of gold. I remember visiting the great Buddhist stupa of Bodhnath just outside Kathmandu and seeing how its pure white body was marked by swirling rust-like stains. At first I thought it was a shame, but then I was told it was a sign that a devotee had given donations to the temple. Washing a few buckets of safflower over such an important stupa is equal to lighting thousands of butter lamps, and is excellent for karma.