Complete History of Jack the Ripper (33 page)

Read Complete History of Jack the Ripper Online

Authors: Philip Sudgen

PC Lamb lost no time in summoning assistance. He sent his fellow constable for the nearest doctor and despatched the energetic Morris Eagle to Leman Street Police Station. The best evidence on the appearance of the fifth victim as she lay dead in Dutfield’s Yard comes from the medical witnesses.

5

It was about ten minutes past one when Lamb’s colleague called at 100 Commercial Road, the residence of Dr Frederick William Blackwell. The doctor had to be roused from his bed but while he struggled into his clothes his assistant, Edward Johnston, accompanied the policeman to Berner Street. Johnston felt the body and

‘found all warm except the hands, which were quite cold.’ By this time, however, the wound in the woman’s throat had stopped bleeding and the stream of blood that had flowed up the yard had clotted. He found very little blood left in the vicinity of the neck.

Dr Blackwell consulted his watch as he arrived on the scene. It was 1.16 a.m. By the light of a policeman’s lantern he made a remarkably detailed examination of the body and two days later reported his findings at the inquest:

The deceased was lying on her left side obliquely across the passage, her face looking towards the right wall. Her legs were drawn up, her feet close against the wall of the right side of the passage. Her head was resting beyond the carriage-wheel rut, the neck lying over the rut. Her feet were three yards from the gateway. Her dress was unfastened at the neck. The neck and chest were quite warm, as were also the legs, and the face was slightly warm. The hands were cold. The right hand was open and on the chest, and was smeared with blood. The left hand, lying on the ground, was partially closed, and contained a small packet of cachous wrapped in tissue paper. There were no rings, nor marks of rings, on her hands. The appearance of the face was quite placid. The mouth was slightly open. The deceased had round her neck a check silk scarf, the bow of which was turned to the left and pulled very tight. In the neck there was a long incision which exactly corresponded with the lower border of the scarf. The border was slightly frayed, as if by a sharp knife. The incision in the neck commenced on the left side, 2½ inches below the angle of the jaw, and almost in a direct line with it, nearly severing the vessels on that side, cutting the windpipe completely in two, and terminating on the opposite side 1½ inches below the angle of the right jaw, but without severing the vessels on that side. I could not ascertain whether the bloody hand had been moved. The blood was running down the gutter into the drain in the opposite direction from the feet. There was about 1 lb. of clotted blood close by the body, and a stream all the way from there to the back door of the club.’

It should be noted that the woman’s clothing had not been disturbed by her killer. Dr Blackwell indeed discovered that her dress had been unfastened at the neck but this had been done by his assistant Edward Johnston during his brief inspection of the body.

In the meantime Dr Phillips, the divisional police surgeon, had

been summoned to Leman Street and sent on from there to Dutfield’s Yard. When he got there Chief Inspector West and Inspector Charles Pinhorn were in possession of the body. The record of his examination, dictated on the spot to Pinhorn, largely corroborates that of Dr Blackwell. It was presented to the inquest by Phillips on 3 October:

The body was lying on its left side, face turned toward the wall, head toward the yard, feet toward the street, left arm extended from elbow, which held a packet of cachous in her hand. Similar ones were in the gutter. I took them from her hand, and handed them to Dr Blackwell. The right arm was lying over the body, and the back of the hand and wrist had on them clotted blood. The legs were drawn up, the feet close to the wall, the body still warm, the face warm, the hands cold, the legs quite warm, a silk handkerchief round the throat, slightly torn (so is my note, but I since find it is cut) . . . This corresponded to the right angle of the jaw; the throat was deeply gashed, and an abrasion of the skin about an inch and a quarter diameter, apparently slightly stained with blood, was under the right clavicle.

6

On a minor point of fact the medicos were in conflict. The victim died clutching a packet of cachous (small aromatic sweetmeats, sucked to sweeten the breath) in her left hand. On 3 October Dr Phillips told the inquest that he released them from her hand and passed them to Dr Blackwell. But Blackwell, recalled before the inquiry two days later, swore:

I removed the cachous from the left hand of the deceased, which was nearly open. The packet was lodged between the thumb and the first finger, and was partially hidden from view. It was I who spilt them in removing them from the hand. My impression is that the hand gradually relaxed while the woman was dying, she dying in a fainting condition from the loss of blood.

Both doctors examined the area about the body as well as the available light permitted. There was a patch of blood on the ground to the left of the neck. From this a stream had run along the gutter to within a few inches of the side door of the club. But Blackwell could find no spots of blood on the dead woman’s clothes or on the

wall of the club. And although he saw other traces on the ground he thought that these had been trodden about on the boots of bystanders. Phillips agreed: ‘I could trace none [blood spots] except that which I considered had been transplanted – if I may use the term – from the original flow from the neck.’

Precisely when did the woman die? Dr Blackwell noted that her hands were cold. But he detected some warmth in her face, and her neck, chest and legs were quite warm. The fact that the clothes were not wet with rain also indicated that she had not been lying in the yard long. On the other hand there were factors present conducive to a slow loss of body heat. The victim would have bled to death comparatively slowly because only the vessels on the left side of the neck had been cut and even then the carotid artery had not been completely severed. Furthermore, the night itself had been very mild. It was Blackwell’s opinion, nevertheless, that when he arrived in the yard the woman could not have been dead ‘more than twenty minutes, at the most half an hour.’ We know that Blackwell reached Dutfield’s Yard at 1.16. He was saying, then, that the murder took place after 12.46 and very possibly after 12.56 a.m.

Dr Phillips informed the inquest that the woman had been alive ‘within an hour’ of his own arrival at the scene of the crime. Since existing versions of his testimony neglect to tell us when that was, however, his statement is difficult to interpret. Blackwell thought that Phillips arrived between twenty and thirty minutes after himself. If so Dr Phillips’ evidence places the time of death after 12.36–12.46 a.m.

While Johnston was examining the body PC Lamb had the yard gates closed and posted a man at the wicket. He then made a cursory investigation of the club premises, turning his light on the hands and clothes of inmates and searching rooms. Finding nothing suspicious, he next turned his attention to the cottages across the way. The tenants had retired for the night. Lamb found them in a state of undress and very frightened. We do not know the details of his exploration of these cottages but under the circumstances it was almost certainly perfunctory. ‘I told them [the tenants] there was “nothing much the matter”,’ he said at the inquest, ‘as I did not wish to scare them more.’ The constable’s preliminary searches also evidently took in Hindley’s store and two waterclosets in the yard. When he returned from his perambulations he found West and Phillips with the body.

Perhaps because Dutfield’s Yard was easily sealed off the police occupied it for some hours. The onlookers that had gathered there were detained until they had been identified and searched by the police and examined for bloodstains by Dr Phillips. The body itself was eventually removed to St George’s Mortuary, Cable Street, and at 5.30 PC Albert Collins washed the last vestiges of gore from the yard. No weapon, no clue to the murderer, had been found.

By then the real centre of the night’s events had long since moved, some three-quarters of a mile and twelve minutes’ walk away, to a small, stone-cobbled square, just within the eastern boundary of the City of London.

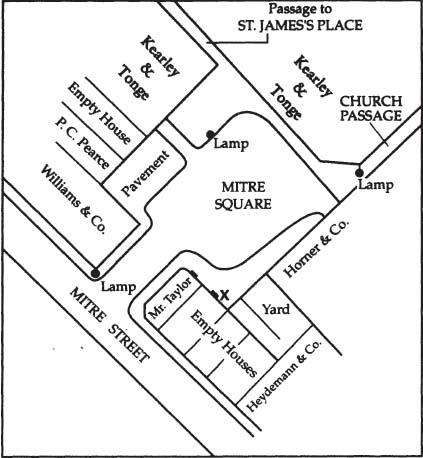

Behind Mitre Street, off Aldgate, is Mitre Square. About twenty-four yards square, it was accounted a ‘respectable’ place, largely comprised of business premises, and was, during business hours, extensively used. But, although close to the junction of Fenchurch Street, Leadenhall Street and Aldgate, Mitre Square was ill-lit and almost deserted after dark. Only two lamps directly illuminated the square itself. A lamp post stood in the northwestern part of it and a ‘lantern lamp’ was affixed to the wall at the entrance of Church Passage, in the eastern corner. The silence of the square after nightfall reflected the relative seclusion of its location and the fact that it could boast but an insignificant resident population, the few houses that existed there, mostly dilapidated and empty, crouching in the shadow of tall warehouses that dominated Mitre Square on every side. ‘This particular square,’ wrote a journalist, ‘is as dull and lonely a spot as can be found anywhere in London.’

7

Ironically the only private residents of Mitre Square at its moment of notoriety were a City policeman – PC Richard Pearce 922 – and his family. They lived at No. 3, one of two tenements in the western corner of the square, sandwiched between the warehouses of Walter Williams & Co. and Kearley & Tonge. The adjacent house was an empty, tumble-down slum with broken windows. These were the only dwelling houses that actually faced into the square. In the southern corner of Mitre Square, fronting upon Mitre Street, was a row of four further houses. Their back windows overlooked the square but no less than three of the houses were empty and the fourth, the shop of Mr Taylor, a picture-frame maker, at the end of the row, was customarily locked-up and unoccupied at nights.

Some of the warehouses did contain caretakers or watchmen. In the southeast part of the square, between the row of empty houses and

Horner & Company’s warehouses was a private yard. It belonged to Messrs Heydemann & Co., general merchants, of 5 Mitre Street, and the second and third floor back windows of their premises, behind the yard, commanded an uninterrupted view of the southern and western parts of Mitre Square. George Clapp, the resident caretaker, slept with his wife in a back room on the second floor. The only other resident in Heydemann’s premises was an old nurse who attended Mrs Clapp. She slept in a room on the third floor. Across the square from Heydemann’s, in the premises of Kearley & Tonge, wholesale grocers, a watchman, George James Morris, started work at 7.00 p.m.

There were three approaches to Mitre Square – one carriageway and two narrow foot passages. The carriageway led into the square from Mitre Street, passing between Mr Taylor’s shop on the right and the Walter Williams & Co. warehouse on the left. At the eastern corner of the square was Church Passage. It communicated with Duke Street. The other passage ran from St James’ Place (‘the Orange Market’) to the northern point of Mitre Square.

At about 1.44 a.m., just three-quarters of an hour after the Dutfield’s Yard discovery, PC Edward Watkins 881 of the City Police approached Mitre Square from Mitre Street. All was quiet. George Clapp and his wife had been in bed since about 11.00 and PC Pearce since 12.30. They were now sleeping soundly. George Morris, Kearley & Tonge’s watchman, was cleaning the offices on the ground floor of their counting house block. PC Watkins’ beat normally took him about twelve or fourteen minutes to patrol. When he had last explored Mitre Square, at about 1.30, it had been deserted. And so, as he stepped into the square, it seemed now. There was no sound but that of his own footsteps. Yet, turning right into the southern corner of the square, the constable beheld in the beam of the lantern fixed in his belt one of the most gruesome sights he had witnessed in seventeen years of police work.

Four days later, before the coroner, Watkins described what he had found in the tersest language: ‘I next came in at 1.44. I turned to the right. I saw the body of a woman lying there on her back with her feet facing the square [and] her clothes up above her waist. I saw her throat was cut and her bowels protruding. The stomach was ripped up. She was laying in a pool of blood.’ To the representatives of the press the constable was a little more expansive. ‘She was ripped up like a pig in the market,’ he told the

Star

, ‘. . . I have been in the force a long while, but I never saw such a sight.’

The Daily News

carried his most detailed account:

Mitre Square.

×

marks the spot where the body of Catherine Eddowes was discovered, at 1.44 a.m. on Sunday, 30 September 1888