Complete Works of Emile Zola (519 page)

Read Complete Works of Emile Zola Online

Authors: Émile Zola

“Hallow, it’s you? Good-day! No jokes! Don’t make me nuzzle your hair.”

And he passed his hand before his face, he blew to send the hairs away. The house surgeon questioned him.

“Who is it you see?”

“My wife, of course!”

He was looking at the wall, with his back to Gervaise. The latter had a rare fright, and she examined the wall, to see if she also could catch sight of herself there. He continued talking.

“Now, you know, none of your wheedling — I won’t be tied down! You are pretty, you have got a fine dress. Where did you get the money for it, you cow? You’ve been at a party, camel! Wait a bit and I’ll do for you! Ah! you’re hiding your boy friend behind your skirts. Who is it? Stoop down that I may see. Damnation, it’s him again!”

With a terrible leap, he went head first against the wall; but the padding softened the blow. One only heard his body rebounding onto the matting, where the shock had sent him.

“Who is it you see?” repeated the house surgeon.

“The hatter! The hatter!” yelled Coupeau.

And the house surgeon questioning Gervaise, the latter stuttered without being able to answer, for this scene stirred up within her all the worries of her life. The zinc-worker thrust out his fists.

“We’ll settle this between us, my lad. It’s full time I did for you! Ah, you coolly come, with that virago on your arm, to make a fool of me before everyone. Well! I’m going to throttle you — yes, yes, I! And without putting any gloves on either! I’ll stop your swaggering. Take that! And that! And that!”

He hit about in the air viciously. Then a wild rage took possession of him. Having bumped against the wall in walking backwards, he thought he was being attacked from behind. He turned round, and fiercely hammered away at the padding. He sprang about, jumped from one corner to another, knocked his stomach, his back, his shoulder, rolled over, and picked himself up again. His bones seemed softened, his flesh had a sound like damp oakum. He accompanied this pretty game with atrocious threats, and wild and guttural cries. However the battle must have been going badly for him, for his breathing became quicker, his eyes were starting out of his head, and he seemed little by little to be seized with the cowardice of a child.

“Murder! Murder! Be off with you both. Oh! you brutes, they’re laughing. There she is on her back, the virago! She must give in, it’s settled. Ah! the brigand, he’s murdering her! He’s cutting off her leg with his knife. The other leg’s on the ground, the stomach’s in two, it’s full of blood. Oh!

Mon Dieu!

Oh!

Mon Dieu!

”

And, covered with perspiration, his hair standing on end, looking a frightful object, he retired backwards, violently waving his arms, as though to send the abominable sight from him. He uttered two heart-rending wails, and fell flat on his back on the mattress, against which his heels had caught.

“He’s dead, sir, he’s dead!” said Gervaise, clasping her hands.

The house surgeon had drawn near, and was pulling Coupeau into the middle of the mattress. No, he was not dead. They had taken his shoes off. His bare feet hung off the end of the mattress and they were dancing all by themselves, one beside the other, in time, a little hurried and regular dance.

Just then the head doctor entered. He had brought two of his colleagues — one thin, the other fat, and both decorated like himself. All three stooped down without saying a word, and examined the man all over; then they rapidly conversed together in a low voice. They had uncovered Coupeau from his thighs to his shoulders, and by standing on tiptoe Gervaise could see the naked trunk spread out. Well! it was complete. The trembling had descended from the arms and ascended from the legs, and now the trunk itself was getting lively!

“He’s sleeping,” murmured the head doctor.

And he called the two others’ attention to the man’s countenance. Coupeau, his eyes closed, had little nervous twinges which drew up all his face. He was more hideous still, thus flattened out, with his jaw projecting, and his visage deformed like a corpse’s that had suffered from nightmare; but the doctors, having caught sight of his feet, went and poked their noses over them, with an air of profound interest. The feet were still dancing. Though Coupeau slept the feet danced. Oh! their owner might snore, that did not concern them, they continued their little occupation without either hurrying or slackening. Regular mechanical feet, feet which took their pleasure wherever they found it.

Gervaise having seen the doctors place their hands on her old man, wished to feel him also. She approached gently and laid a hand on his shoulder, and she kept it there a minute.

Mon Dieu!

whatever was taking place inside? It danced down into the very depths of the flesh, the bones themselves must have been jumping. Quiverings, undulations, coming from afar, flowed like a river beneath the skin. When she pressed a little she felt she distinguished the suffering cries of the marrow. What a fearful thing, something was boring away like a mole! It must be the rotgut from l’Assommoir that was hacking away inside him. Well! his entire body had been soaked in it.

The doctors had gone away. At the end of an hour Gervaise, who had remained with the house surgeon, repeated in a low voice:

“He’s dead, sir; he’s dead!”

But the house surgeon, who was watching the feet, shook his head. The bare feet, projecting beyond the mattress, still danced on. They were not particularly clean and the nails were long. Several more hours passed. All on a sudden they stiffened and became motionless. Then the house surgeon turned towards Gervaise, saying:

“It’s over now.”

Death alone had been able to stop those feet.

When Gervaise got back to the Rue de la Goutte-d’Or she found at the Boches’ a number of women who were cackling in excited tones. She thought they were awaiting her to have the latest news, the same as the other days.

“He’s gone,” said she, quietly, as she pushed open the door, looking tired out and dull.

But no one listened to her. The whole building was topsy-turvy. Oh! a most extraordinary story. Poisson had caught his wife with Lantier. Exact details were not known, because everyone had a different version. However, he had appeared just when they were not expecting him. Some further information was given, which the ladies repeated to one another as they pursed their lips. A sight like that had naturally brought Poisson out of his shell. He was a regular tiger. This man, who talked but little and who always seemed to walk with a stick up his back, had begun to roar and jump about. Then nothing more had been heard. Lantier had evidently explained things to the husband. Anyhow, it could not last much longer, and Boche announced that the girl of the restaurant was for certain going to take the shop for selling tripe. That rogue of a hatter adored tripe.

On seeing Madame Lorilleux and Madame Lerat arrive, Gervaise repeated, faintly:

“He’s gone.

Mon Dieu!

Four days’ dancing and yelling — “

Then the two sisters could not do otherwise than pull out their handkerchiefs. Their brother had had many faults, but after all he was their brother. Boche shrugged his shoulders and said, loud enough to be heard by everyone:

“Bah! It’s a drunkard the less.”

From that day, as Gervaise often got a bit befuddled, one of the amusements of the house was to see her imitate Coupeau. It was no longer necessary to press her; she gave the performance gratis, her hands and feet trembling as she uttered little involuntary shrieks. She must have caught this habit at Sainte-Anne from watching her husband too long.

Gervaise lasted in this state several months. She fell lower and lower still, submitting to the grossest outrages and dying of starvation a little every day. As soon as she had four sous she drank and pounded on the walls. She was employed on all the dirty errands of the neighborhood. Once they even bet her she wouldn’t eat filth, but she did it in order to earn ten sous. Monsieur Marescot had decided to turn her out of her room on the sixth floor. But, as Pere Bru had just been found dead in his cubbyhole under the staircase, the landlord had allowed her to turn into it. Now she roosted there in the place of Pere Bru. It was inside there, on some straw, that her teeth chattered, whilst her stomach was empty and her bones were frozen. The earth would not have her apparently. She was becoming idiotic. She did not even think of making an end of herself by jumping out of the sixth floor window on to the pavement of the courtyard below. Death had to take her little by little, bit by bit, dragging her thus to the end through the accursed existence she had made for herself. It was never even exactly known what she did die of. There was some talk of a cold, but the truth was she died of privation and of the filth and hardship of her ruined life. Overeating and dissoluteness killed her, according to the Lorilleuxs. One morning, as there was a bad smell in the passage, it was remembered that she had not been seen for two days, and she was discovered already green in her hole.

It happened to be old Bazouge who came with the pauper’s coffin under his arm to pack her up. He was again precious drunk that day, but a jolly fellow all the same, and as lively as a cricket. When he recognized the customer he had to deal with he uttered several philosophical reflections, whilst performing his little business.

“Everyone has to go. There’s no occasion for jostling, there’s room for everyone. And it’s stupid being in a hurry that just slows you up. All I want to do is to please everybody. Some will, others won’t. What’s the result? Here’s one who wouldn’t, then she would. So she was made to wait. Anyhow, it’s all right now, and faith! She’s earned it! Merrily, just take it easy.”

And when he took hold of Gervaise in his big, dirty hands, he was seized with emotion, and he gently raised this woman who had had so great a longing for his attentions. Then, as he laid her out with paternal care at the bottom of the coffin, he stuttered between two hiccoughs:

“You know — now listen — it’s me, Bibi-the-Gay, called the ladies’ consoler. There, you’re happy now. Go by-by, my beauty!”

THE END

A LOVE EPISODE

Translated by Ernest Alfred Vizetelly

The eighth novel in the

Rougon-Macquart

series,

Une Page d’amour

is set among the petite bourgeoisie in Second Empire suburban Paris. Originally serialised between December 1877 and April 1878 in

Le Bien public

, before being published in novel form by Charpentier, it involves Hélène Grandjean, née Mouret, who was briefly introduced in the first novel of the cycle. Hélène is the daughter of Ursule Mouret née Macquart, the illegitimate daughter of Adelaïde Fouque, the ancestress of the Rougon-Macquart family. Hélène’s brothers are François Mouret, the central character of

La Conquête de Plassans

and Silvère Mouret, whose history is related in

La Fortune des Rougon.

The narrative takes place over a year, from 1854 to 1855, opening with Hélène as a widow, living in the Paris suburb of Passy with her eleven year old daughter Jeanne. Her husband Charles Grandjean had fallen ill the day after they arrived from Marseilles and died eight days later. Though rarely venturing into Paris, Hélène and Jeanne can view the entire city from the window of their home, which they regard with a romantic, yet awe-struck wonder. On the night the novel opens, Jeanne has fallen ill with a violent seizure. In panic, Hélène runs into the street to find a doctor, desperate to preserve the life of her child.

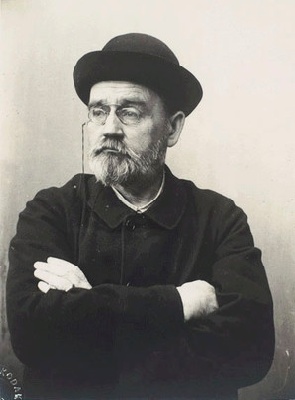

Zola, c.1900

CONTENTS