Conceived in Liberty (115 page)

Read Conceived in Liberty Online

Authors: Murray N. Rothbard

In the fall of 1739, England launched an aggressive war against Spain, and this was all the signal needed by Georgia or the Spaniards, eager to repulse the Oglethorpe thrusts. Characteristically, the first mass attack was launched in 1740 by General Oglethorpe, in an attempt to conquer the chief Spanish fort of St. Augustine. Commanding South Carolinian and Indian forces and bolstered by the huge cash subsidy of 120,000 pounds granted by South Carolina, Oglethorpe besieged St. Augustine by land and sea. The siege, however, failed completely and Oglethorpe ungratefully and characteristically sought to use South Carolina as a scapegoat for his own failure. Oglethorpe’s bitter charges naturally provoked retaliation in South Carolina, and Carolinian charges of incompetence hit far closer to the mark.

Two years later, the Spaniards retaliated and landed an expedition of several thousand men against Frederica, but were repulsed in a cleverly executed ambush by the heavily outnumbered Oglethorpe. But the result of this Battle of Bloody Marsh was owing far more to Spanish incompetence than to the excellence of Oglethorpe’s defense. For his part, after failing to gain English aid by arousing hysteria in England about the supposedly imminent attack from Florida, Oglethorpe struck out on his own in the spring of 1743 to try once again to capture St. Augustine. But the Spanish repulsed the attack. The new result of the various military clashes between Georgia and Florida was a stalemate and a maintenance of the status quo. With the aggressive Oglethorpe having returned to England, the war with Spanish Florida was now at an end.

The humanitarian Oglethorpe had been most anxious to use his charges for military fodder; stringent military training and discipline had, from the beginning, been imposed upon the colonists. Among the hundreds of German immigrants to Georgia was a group of Protestant Moravians. This pacifist sect resisted military training and nonexemption from such conscription. When the war with Spain began, Georgia renewed its demand upon the Moravians, who courageously replied that “they could not in conscience fight and if expected to do so, they must leave the country.” This they promptly proceeded to do, and migrated to the far more hospitable valley of Pennsylvania.

Another religious group that arrived during the trustee period was several score of Jews, who landed in July 1733. Three of the wealthiest Sephardic Jews (of Spanish-Portuguese descent) in London were hired as fund-raisers to collect charitable sums for the Georgia project. The three agents were, of course, supposed to turn over the funds to the trustees. Instead, they blithely used the money to finance the emigration of two groups of Jews to Georgia. The more notable group consisted of forty Sephardic Jews, while the other party was made up of much poorer folk from Germany. The trustees were understandably embittered at this chicanery, and ordered Oglethorpe to eject

the Jews from the colony. Particularly bitter and alarmed was the religiously oriented Thomas Coram, who warned the trustees that Georgia “would soon become a Jewish colony,” with only Christian laborers—those whom the Jews “find most necessary and useful”—allowed to remain in the country. Oglethorpe, however, was greatly impressed with the way that a Jewish physician, Dr. Samuel Nuñez Ribiero, was able to stop a severe epidemic, and allowed them to stay. The Jews settled in Savannah, but in a few years the bulk of them had migrated to Charleston.

*

After a royal government replaced the hated proprietary in 1752, Georgia swiftly became very much like the other royal colonies in America. The end of proprietary planning led to rapid growth of the colony, with rice and indigo culture spreading in the lowlands in lieu of such unfortunate projects as silk. With slavery now permitted and the land free of encumbrance, large plantations for rice and indigo could be profitably established. “South Carolina,” in fact, moved to the coast of northern Georgia. In addition, timber and naval stores were now widely grown in the new royal province. Also arriving in Georgia was a group of several hundred Puritans, originally from Massachusetts, who now settled the Midway district on the coast, around the port of Sunbury. All in all, Georgia began to resemble an undeveloped microcosm of her neighbor to the north, including the typical royal-colony scheme of appointed governor and Council in conflict with an elective representative Assembly. In 1758, Georgia joined the other Southern colonies in establishing the Anglican church. Dissenters continued to flourish in the colony, but soon attendance at public religious services was made compulsory.

After Oglethorpe’s departure, the forts south of the Altamaha were allowed to fall into decay, and the Crown refused to spend money to rebuild what could only serve as a standing challenge to Spain. Unoccupied and free of the burdens of imposed sovereignty, the region south of the Altamaha became a truly free land. Like Rhode Island and North Carolina in the mid-seventeenth century, it became in the 1750s an individualistic haven for those discontented with existing governments.

The most prominent dissident was Edmund Gray, a Quaker from Virginia. Gray had already become influential in Augusta for openly daring to parcel out land in the public domain to himself and to his fellow settlers without bothering to worry about governmental sanction. Running for the first royal Assembly, meeting in early 1755, Gray stirred up the people with eloquent pleas for liberty and economic opportunity as well as criticism of emerging royal rule. In the election, Gray won the Assembly seat from Augusta, and the head of the Gray forces in Savannah, the lawyer Charles Watson, was elected from that city. Gray claimed that the defeat of two of his other allies in the Savannah election was due to fraud. Not only did the Assembly reject this

claim, but it went on to expel two other followers of Gray. This arbitrary act precipitated a boycott of the lower house by Gray, Watson, and six other representatives, constituting almost half of the total membership of the Assembly. The Assembly replied by expelling two more of the absentees, who now issued a circular letter on January 15 to the freeholders of Georgia, calling upon all “who regard the liberties of your country” to flock to Savannah.

John Reynolds, the first royal governor, reacted to this crisis with an hysterical and coercive crackdown on his opposition. He denounced the “sedition,” decreed the prohibition of “all tumultuous assemblies and nightly meetings,” urged his subjects to defend the imperiled government, and formed a counterrevolutionary armed association, headed by the Council and the rump Assembly. Upon this demonstration of

force majeure,

Gray and Watson fled Savannah, and the Assembly peremptorily expelled all of its “seditious” members. Disgusted with Georgia’s arbitrary actions, Gray and several hundred followers left Georgia to settle south of the Altamaha, where no long arm of government could reach them.

This settlement of Gray and his followers centered on Cumberland Island and the new settlement of New Hanover, some miles up the Satilla River. There Gray and his followers lived free lives, unburdened by the domination of government. As such, their very existence was a standing reproach to the people of Georgia, and especially to its government, who concluded that these “dangerous” people must be stamped out lest their example be followed by others. Furthermore, governments always abhor a “vacuum,” and Spain was trying to force Gray and his followers to come under its jurisdiction. Consequently, the Crown itself, in 1758, ordered these free settlements crushed. Officials from South Carolina and Georgia traveled there and successfully ordered them to disburse and leave the territory of no-government. The haven from government was at an end. Gray, however, proved indomitable and reestablished New Hanover, with over seventy families, on Cumberland Island in 1761.

During the Seven Years’ War, from 1756 to 1763, Spain entered the war just long enough to be the loser on France’s side. Consequently, at the peace treaty of 1763, the Spanish were forced to cede all of Florida to England. Florida was made a royal colony, and the Florida-Georgia border fixed at the St. Mary’s River—to the chagrin of Georgia, which demanded the line of the St. John’s. But, in any case, Georgia had now seized jurisdiction over the trans-Altamaha region and the land of no-government was finally no more.

In the meanwhile, the ruling South Carolina oligarchy had executed a brazen maneuver; claiming sovereignty over the trans-Altamaha, Governor Thomas Boone airily granted almost 350,000 acres of its land to the two hundred leading planters of his colony, including Henry Laurens and Henry Middleton. Governor James Wright of Georgia promptly protested to the Crown over this arbitrary land grab; the engrossment by land speculators

would shut off an expected flow of settlers, the “sinews, wealth, and strength of an infant colony.” Moreover, the grants were unfair to the people of Georgia, to the settlers who bore the “brunt and fatigue of settling a new colony.” The Crown, however, proved reluctant to dispossess the grantees and this despite the fact that the peace treaty had granted the trans-Altamaha region to Georgia.

In 1765, Georgia decided in eminently fair fashion to confer land grants only to the extent that the land was cleared and settled, and the Crown finally approved a similar provision. As it turned out, the meager demand for this land during the remainder of the colonial era made the entire problem academic.

Despite its recent rapid growth, Georgia still remained the smallest and weakest English colony; its crippling heritage under trusteeship had not been fully overcome. But now it was set for further rapid expansion, especially as the Creek Indians were rewarded for their faithful alliance with the English against the dangerous Cherokees—by being forced to leave their lands in eastern Georgia.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Charles Allen Munn, 1924

Rev. Jonathan Mayhew

Courtesy of The New-York Historical Society

Jonathan Edwards

Courtesy of The New-York Historical Society

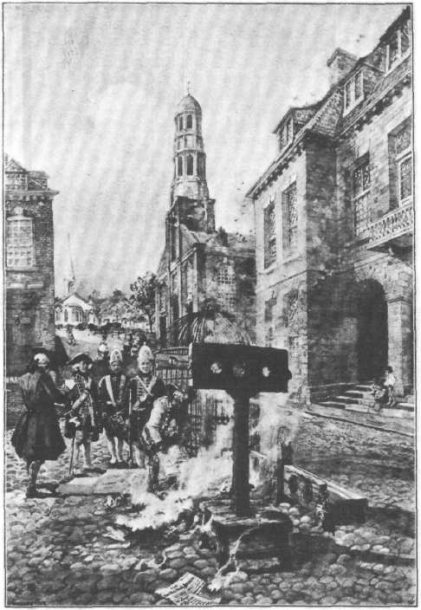

Burning Peter Zenger’s

Weekly Journal

on Wall Street

New York Public Library

Robert Walpole