Confusion: Cazalet Chronicles Book 3

Read Confusion: Cazalet Chronicles Book 3 Online

Authors: Elizabeth Jane Howard

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Classics, #Contemporary, #Genre Fiction, #Family Saga, #Historical, #Literary, #Women's Fiction, #Domestic Life, #Romance, #Contemporary Fiction, #Family Life, #Sagas, #Literary Fiction

For my brothers,

Robin and Colin Howard

CONTENTS

The Cazalet Family and their Servants

The Family

: Late Summer–Autumn 1942

THE CAZALET FAMILY AND THEIR SERVANTS

W

ILLIAM

C

AZALET

, known as the Brig

Kitty Barlow

, known as the Duchy (his wife)

Rachel, their unmarried daughter

H

UGH

C

AZALET

, eldest son

Sybil Carter

(his wife)

Polly

Simon

William, known as Wills

E

DWARD

C

AZALET

, second son

Viola

, known as Villy (his wife)

Louise

Teddy

Lydia

Roland, known as Roly

R

UPERT

C

AZALET

, third son

Zoë

(second wife)

Juliet

Isobel

(first wife; died having Neville)

Clarissa, known as Clary

Neville

J

ESSICA

C

ASTLE

(Villy’s sister)

Raymond

(her husband)

Angela

Christopher

Nora

Judy

Mrs Cripps (cook)

Ellen (nurse)

Eileen (parlourmaid)

Peggy and Bertha (housemaids)

Dotty, Edie and Lizzie (kitchenmaids)

Tonbridge (chauffeur)

McAlpine (gardener)

Wren (groom)

FOREWORD

The following background is intended for those readers who have not read

The Light Years

and

Marking Time

, the two previous volumes of this Chronicle.

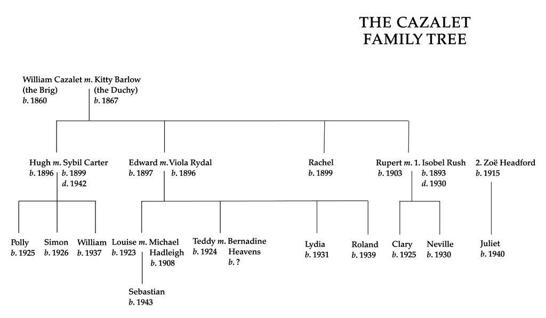

William and Kitty Cazalet, known to their family as the Brig and the Duchy, are spending the war in Home Place, their country house in Sussex. The Brig is now virtually blind and hardly goes to London any more to preside over the family timber firm. They have three sons and an unmarried daughter, Rachel.

The eldest son, Hugh, married to Sybil, has three children, Polly, Simon and William (Wills). Polly does lessons at home, Simon is at public school, and Wills is four. Sybil has been very ill for some months.

Edward is married to Villy and has four children. Louise is succumbing to love – with Michael Hadleigh, a successful portrait painter, older than she, now in the Navy – rather than an acting career. Teddy is about to go into the RAF. Lydia does lessons at home and Roland (Roly) is a baby.

Rupert, the third son, has been missing in France since Dunkirk in 1940. He was married to Isobel by whom he had two children; Clary, who does lessons with her cousin, Polly, (but she and Polly are eager to get to London and start grown-up life), and Neville, who goes to a prep school. Isobel died having Neville, and subsequently Rupert married Zoë who is far younger than he. She had a daughter, Juliet, shortly after he disappeared, whom he has never seen.

Rachel lives for others, which her great friend, Margot Sidney (Sid), who is a violin teacher in London, often finds hard.

Edward’s wife Villy has a sister, Jessica Castle, who is married to Raymond. They have four children. Angela, the eldest, lives in London and is prone to unhappy love affairs; Christopher has fragile health and now lives a reclusive life in a caravan with his dog. He works on a farm. Nora is nursing and Judy is away at school. The Castles have inherited some money and a home in Surrey.

Miss Milliment is the very old family governess: she began with Villy and Jessica, and now teaches Clary, Polly and Lydia.

Diana Mackintosh, a widow, is the most serious of Edward’s affairs. She is expecting a child. Both Edward and Hugh have houses in London but Hugh’s in Ladbroke Grove is the only home being inhabited at present.

Marking Time

ended with the news that Rupert is still alive and with the Japanese attacking Pearl Harbor.

Confusion

opens in March 1942 just after Sybil has died.

PART ONE

POLLY

March 1942

The room had been shut up for a week; the calico blind over the window that faced south over the front garden had been pulled down; a parchment-coloured light suffused the cold, stuffy air. She went to the window and pulled the cord; the blind flew up with a snap. The room lightened to a chill grey – paler than the boisterous cloudy sky. She stayed for a moment by the window. Clumps of daffodils stood with awful gaiety under the monkey puzzle, waiting to be sodden and broken by March weather. She went to the door and bolted it. Interruption, of any kind, would not be bearable. She would get a suitcase from the dressing room and then she would empty the wardrobe, and the drawers in the rosewood chest by the dressing table.

She collected a case – the largest she could find – and laid it on the bed. She had been told never to put suitcases on beds, but this one had been stripped of its bedclothes and looked so flat and desolate under its counterpane that it didn’t seem to matter.

But when she opened the wardrobe and saw the long row of tightly packed clothes she suddenly dreaded touching them – it was as though she would be colluding in the inexorable departure, the disappearance that had been made alone and for ever and against everyone’s wishes, that was already a week old. It was all part of her not being able to take in the for-ever bit: it was possible to believe that someone was gone; it was their not ever coming back that was so difficult. The clothes would never be worn again and, useless to their one-time owner, they could only now be distressing to others – or rather, one other. She was doing this for her father, so that when he came back from being with Uncle Edward he would not be reminded by the trivial, hopeless belongings. She pulled out some hangers at random; little eddies of sandalwood assailed her – together with the faint scent that she associated with her mother’s hair. There was the green and black and white dress she had worn when they had gone to London the summer before last, the oatmeal tweed coat and skirt that had always seemed either too big or too small for her, the very old green silk dress that she used to wear when she had evenings alone with Dad, the stamped velvet jacket with marcasite buttons that had been what she had called her concert jacket, the olive-green linen dress that she had worn when she was having Wills – goodness, that must be five years old. She seemed to have kept everything: clothes that no longer fitted, evening dresses that had not been worn since the war, a winter coat with a squirrel collar that she had never

seen

before . . . She pulled everything out and put it on the bed. At one end was a tattered green silk kimono encasing a gold lamé dress that she dimly remembered had been one of Dad’s more useless Christmas presents ages ago, worn uneasily for that one night and never again. None of the clothes were really nice, she thought sadly – the evening ones withered from hanging so long without being worn, the day clothes worn until they were thin, or shiny or shapeless or whatever they were supposed

not

to be. They were all simply jumble sale clothes, which Aunt Rach had said was the best thing to do with them, ‘although you should keep anything you want, Polly darling,’ she had added. But she didn’t want anything, and even if she had, she could never have worn whatever it might have been because of Dad.

When she had packed the clothes away she realised that the wardrobe still contained hats on the top shelf and racks of shoes beneath the clothes. She would have to find another case. There was only one other – and this time it had her mother’s initials upon it, ‘S.V.C.’ ‘Sybil Veronica’ the clergyman had said at the funeral – how odd to have a name that had never been used except when you were christened and buried. The dreadful picture of her mother lying encased and covered with earth recurred as it had so many times this week; she found it impossible not to think of a body as a person who needed air and light. She had stood dumb and frozen during the prayers and scattering of earth and her father dropping a red rose onto the coffin, knowing that when they had done all that they were going to leave her there – cold and alone for ever. But she could say none of this to anyone; they had treated her as a child about the whole thing, had continued till the end to tell her cheerful, bracing lies that had ranged from possible recovery to lack of pain and finally – and they had not even perceived the inconsistency – to a merciful release (where was the mercy if there had been no pain?). She was

not

a child, she was nearly seventeen. So beyond this final shock – because, of course, she had

wanted

to believe the lies – she now felt stiff with resentment, with

rage

at not being considered fit for reality. She had slid from people’s arms, evaded kisses, ignored any consideration or gentleness all the week. Her only relief was that Uncle Edward had taken Dad away for two weeks, leaving her free to hate the rest of them.