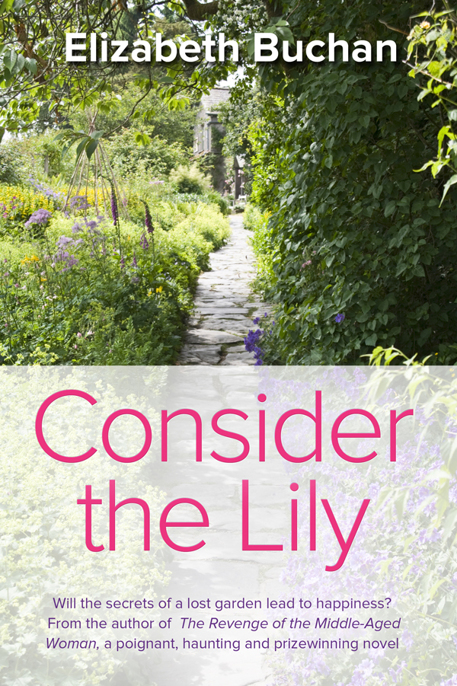

Consider the Lily

Authors: Elizabeth Buchan

ELIZABETH BUCHAN

* * *

FOR ELEANOR ROSE, MY PARTICULAR FLOWER

* * *

‘

An outstanding, beautifully written story’ -

Good Book Guide

‘

A gorgeously well-written tale, funny, sad, sophisticated’

– Independent

‘

The literary equivalent of an English country garden’ –

Sunday Times

Hinton Dysart and its estate are dying through lack of money and from the haemorrhage of energy and hope bought about by the First World War. Its inhabitants have suffered and Kit Dysart, caught between the woman he loves and the need to do something, is trapped. So, too, is the life-enhancing vivid Daisy and her cousin, the rich, unhappy Matty Verral.

Drawn together by powerful emotions, the three are caught up in a cycle of family history. But when Matty, fretting and solitary, decides to re-create a garden, she discovers solace, new hope and future of which she had never dreamed.

A glorious fusion of love, gardening, passion and loss, spun through with a history of flowers and the ghosts from the past

, Consider the Lily

is a poignant and haunting novel of life between two world wars.

‘

Excellent… strong imaginative power , wonderful sense of atmosphere’

Joanna Trollope

Although some readers will recognize the topography and description of Nether Hinton, I would like to assure them that both Hinton Dysart and its garden are imaginary. So, too, is the loop of the river which I have boldly relocated. Similarly, none of the characters in the book are based on living persons.

Several people were instrumental in the writing. Ursula Buchan who took time off from her own book and hectic schedule to help, advise and redirect me where I went wrong. I am greatly indebted and grateful. Fred Stevens without whom this book could not have been written. His generosity in giving me his time and allowing me to plunder his book,

Crondall Then

(available in the village stores) is boundless. So, too, is his gardening skill. Kate Chevenix Trench and Sarah Bailey for their sensitive input. Jane Wood, Suzanne Baboneau, Hazel Orme and Caroline Sheldon for their faith, expertise and hard work.

I would also like to thank David Austin for sending me information and photographs about his English Roses. Any mistake is mine. Also my sisters, Alison Souter and Rosie Hobhouse. Not only are they loyal supporters cheering on from the line, but also my chief critics. I have not forgotten the lunch club.

I read, enjoyed and mined for information hundreds of books. Chief among them:

An Anthology of Garden Writing. The Lives and Works of Five Great Gardeners,

Ursula Buchan (Croom Helm, 1986),

Flowers and their Histories,

Alice M. Coats (Hulton Press, 1956),

A War Imagined: The First World War and English Culture,

Samuel Hynes (Bodley Head, 1990),

1939, The Last Season of Peace,

Angela Lambert (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980),

The Private Life of a Country House (1912—1939),

Lesley Lewis (David and Charles, 1980),

1914

(Michael Joseph, 1987) and

Somme

(Michael Joseph, 1983), two unforgettable books by Lynn Macdonald from which I took incidents and verbatim reports,

Medieval English Gardens,

Teresa McLean (Barrie and Jenkins, 1989),

The Countryside Remembered,

Sadie War (Century, 1991).

The number of gardening books on the market are legion but I would like to mention two in particular:

Making a White Garden,

Joan Clifton (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1990), and

The Flowering Year,

Anna Pavord (Chatto and Windus, 1991). Again I took many ideas and made use of the expertise in the books and would like to acknowledge the fact.

Lastly, yet again my family have had to put up with a great deal. To my parents, my husband, Benjamin, and my children, Adam and Eleanor, thank you.

In the garden, more grows than a gardener sows

Spanish proverb

DAISY

1929-30

CHAPTER ONE

It began with a wedding in June 1929.

Matilda Verral – who hated waste and anything to do with horses and who was always known as Matty – stepped from the path across the ironwork bridge over the river and into the south garden of Hinton Dysart. Behind her lay the grassy hump that hid the remains of an earlier Tudor building, a cluster of oak and beech trees and the pink-red wall that the original Sir Harry Dysart had ordered built around the house and garden to enclose it. In front of Matty was the new house, although that was a comparative term, surrounded by a wilderness of tangled and rampant plant life which threw itself against the house’s beautiful walls, and sucked life from the wood and stone. Couch grass, nettles and creeping convolvulus embroidered the terrace under the south-facing windows and the parterre below, in which a few woody-looking roses struggled for survival. On its east wall a

Clematis montana

throttled a ‘Bobby James’ rambling rose. Lush and clover-filled, the grass swished up against the trees and through the once perfect yew circle that sealed off the top lawn from the lower.

It was an Eden, an English Eden, from which the magic had been leeched through neglect. A spoilt Paradise from which hope had trickled away.

Matty stood drinking in the scene, a small, well-dressed, nervous figure, chilled by the sight, but not sure why. Perhaps it was the waste. Perhaps there was something in the atmosphere. Or perhaps it was the cool, weed-filled river which reflected the trees in a dappled spectrum which made her shiver.

She jumped as a couple of guests, stiff and hot-looking in their outfits, walked over the bridge and stopped beside her.

‘Just follow the path,’ said one of the men to Matty, assuming she was lost.

‘Thank you.’ Matty shook herself into attention and, treading carefully in her high heels through the blighted garden, did as they suggested.

Only two hours earlier the cousins had been dressing in the spare bedroom of their hosts who lived just outside the village of Nether Hinton. Neither Matty nor Daisy had brought a maid down from London and the Lockhart-Fifes had none to spare – so shocking, said Daisy who loved to tease, how one has to make do in the country.

One leg crossed over the other, she sat in the puffed chintz bedroom chair and buffed her nails while Ivy Prosser, a village girl with ambitions to better herself, coped with the challenge of dealing with Londoners.

‘Matty. Those earrings don’t suit the dress, nor do they suit you.’ In general, Daisy said what she thought, but since she was rarely malicious and because she talked good sense, she was often consulted and always forgiven. It was part of her charm. ‘Lend them to me instead, Matty. Do.’

Her cousin looked up from the jewellery case on the dressing table littered with silver-topped pots, brushes and a powder bowl. The mirror reflected a comfortable, but Englishly shabby, bedroom, the sash window wedged open with newspaper and two beds covered in unfortunate pink cretonne. Ivy was brushing Matty’s fine, foxy-coloured hair with hands that were not quite steady. The triangle of face beneath an unflattering bob did not register anything, but inside her Matty felt her black demon stir. Picking up the earrings from the box, she screwed them into her ears where they hung, opulent and too large.

‘I want to wear them,’ she said with the nervous shake of her head which always made Daisy’s teeth grit.

A tension in the room deepened. Daisy looked at her cousin – at the bird bones of her wrists and ankles, at the pale face with its prominent

café-au-lait-

coloured eyes that were so frequently scared and troubled, at the surprisingly full lower lip – and shrugged. Ivy helped Matty out of her dressing gown to reveal a crêpe-de-Chine, lace-edged corset which made absolutely no impression on Matty’s sparse figure. With a swish of silk, Daisy, who had been endowed with long limbs, slenderness and a full, firm bosom, got up, took Matty’s place on the stool and began to spread Elizabeth Arden’s Ultra Amoretta foundation over her cheekbones.

‘Is marriage an outdated institution?’ she asked her reflection in the mirror. ‘The Archbishop of Canterbury puts the question to Douglas Fairbanks Junior, nineteen, and Joan Crawford, twenty-three, film star and cigarette card pin-up. Neither party will comment but get married all the same.’ She pulled a face.

Despite herself, Matty smiled. Daisy so often put her finger on the funny or irreverent side of things, on the slant that Matty often considered but never had the courage to express. The unexpected, provoking gibe or

aperçu

that made people laugh and contributed to Daisy’s mystique.

‘After all, we don’t know the Dysarts.’ Daisy turned her attention to her neck. ‘So why are we here? Getting married should be an intimate business. I don’t want strangers staring at me when I give away my life.’

Matty raised her eyebrows. ‘I thought you wanted a big wedding.’

‘Yes. And then again no.’ Daisy, who certainly planned on a substantial affair, took off the lid of the powder jar and shook out the swansdown puff. The sweetish odour in the bedroom intensified. As she powdered her nose, Daisy shot her cousin a look.

‘Anyway, we do know the Dysarts,’ Matty plodded on. ‘We met Polly and her father at the ball last year, and the Lockhart-Fifes can’t

not

go as they are such close neighbours and made such a fuss about bringing us.’

‘We could stay behind.’

Ivy moved away, picked up Matty’s discarded dressing gown, smoothed it with reverent fingers and hung it up.

Unintentionally, the cousins’ eyes collided in the mirror. A childhood of misunderstanding was contained in the exchange, an accumulation of irritation and impatience – exasperation on Daisy’s side, stubbornness born of desperation on Matty’s. The moment passed: Daisy lowered her lids, applied Vaseline liberally and questioned, not for the first time, the Almighty’s wisdom in so arranging it that one could never choose one’s relations. Matty lowered her hat onto her head, speared it with a hat pin and picked up her handbag and gloves. It was too late to remove the earrings which did, indeed, look wrong. As she let herself out of the room, Matty acknowledged that, once again, she had been manoeuvred into taking the wrong decision. It would have been so easy to agree with Daisy, even to have lent her the earrings. Instead, she had taken refuge in a pride that had never served her well.

Assorted prints of horses and birds lined the staircase, interspersed with photographs of hearty Lockhart-Fifes in cricketing gear or colonial uniforms. Matty pulled on her gloves as she went down, reflecting that it was so much easier not to have to deal with people, how much better the world would be if she were the only person in it, and shuddered at the prospect of a whole afternoon trying to keep conversationally afloat.

Upstairs, left to the undivided attentions of Ivy, Daisy sprayed herself liberally with Matty’s L’Origan scent and directed the girl to sprinkle some onto her handkerchief.

Consider the lily, my mother said.

It is one of the most famous and celebrated of flowers. Sometimes confused with other plants that steal from its lustre – like the Guernsey lily – it is, to be strictly precise, a bulbous, herbaceous perennial whose genus is closely related to the amaryllids, irises, orchids and, surprisingly, not so far removed from grasses and sedges.

And yet... and yet, it is a flower that keeps its secrets.

Swaddled by three outer sepals, the bud conceals three inner petals, and on each is traced a nectary furrow leading to the heart of the bloom. There, attached to a trilobed stigma (I like using the proper names: they pin down the chaos of things)... is the ovary surrounded by three filaments. At the tip of the filaments are the anthers. Weighed down by their sticky pollen these swing freely and shower golden rain.

And the flower itself releases an erotic, haunting scent that drifts, half remembered in dreams, half captured in the olfactory memory — but never quite. That, of course, is its power.

Long ago the lily was used as a fertility symbol. Later, it was stolen by the Christians and used in their worship of Mary, the Mother of Jesus: and the lily, both fertile and pure, became the perfect symbol for the Annunciation. One of the many lily legends runs thus: when the Virgin Mary died and ascended into heaven lilies were found massed in her tomb.

St Catherine’s vision of Paradise was characterized by angels wearing lily wreaths and when she died her blood was said to have flowed as white as the lily. Lilies were grown in monastery gardens and, in a suitably English variation, in rectory gardens, used by the clergy for Lady altar and Lady chapel decorations.

But I think the lily is too strong and too flamboyant for chastity.

You see, it is not a flower to grow in woods alongside the violets and drifts of bluebells. The lily belongs in a garden where it can be seen: elegant, intoxicating and airily poised. For the sweet short summer season before oblivion.

Consider the rose.