Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 (14 page)

Read Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

Winters on the Bosphorus can be surprisingly severe, as the Arabs had discovered during the siege of 717. The site of the city, jutting out into the straits, leaves it exposed to fierce squalls hurtling down from the Black Sea on the north wind. A particularly dank and sub-zero cold penetrates to the marrow of the bones; weeks of cheerless rain can churn the streets into mud and prompt flash floods down the steep lanes; sudden snowstorms arise as if from nowhere to obliterate the Asian shore half a mile away then vanish as quickly as they have come; there are long still days of muffling fog when an eerie silence seems to

hold the city in an iron grasp, choking the clappers in church bells and deadening the sound of hooves in the public squares, as if the horses were shod in boots of felt. The winter of 1452–53 seems to have afflicted the citizens with particularly desolate and unstable weather. People observed ‘unusual and strange earthquakes and shakings of the earth, and from the heavens thunder and lightning and awful thunderbolts and flashing in the sky, mighty winds, floods, pelting rain and torrential downpours’. It did not improve the overall mood. No flotillas of Christian ships came to fulfil the promises of union. The city gates remained firmly closed and the supply of food from the Black Sea dried up under the sultan’s throttle. The common people spent their days listening to the words of their Orthodox priests, drinking unwatered wine in the taverns and praying to the icon of the Virgin to protect the city, as it had in the Arab sieges. A hysterical concern for the purity of their souls seized the people, doubtless influenced by the fulminations of Gennadios. It was considered sinful to have attended a liturgy celebrated by a unionist or to have received communion from a priest who was present at the service of union, even if he were simply a bystander to the rites. Constantine was jeered as he rode in the streets.

Seal depicting the protecting Virgin

Despite this unpromising atmosphere, the emperor made what plans he could for the city’s defence. He dispatched envoys to buy food from the Aegean islands and beyond: ‘wheat, wine, olive oil, dried figs, chick peas, barley and other pulses’. Work was put in hand to repair neglected sections of the defences – both the land and sea walls. There was a shortage of good stone and no possibility of obtaining more

from quarries outside the city. Materials were scrounged from ruined buildings and abandoned churches; even old tombstones were pressed into service. The ditch was cleared out in front of the land wall and it appears that despite their reservations, Constantine was successful in persuading the populace to participate in this work. Money was raised by public collection from individuals and from the churches and monasteries to pay for food and arms. All the available weapons in the city – of which there were far too few – were called in and redistributed. Armed garrisons were dispatched to the few fortified strongholds still held by Byzantium beyond its own walls: at Selymbria and Epibatos on the north shore of the Marmara, Therapia on the Bosphorus beyond the Throat Cutter, and to the largest of the Princes’ Islands. In a final gesture of impotent defiance, Constantine sent galleys to raid Ottoman coastal villages on the Sea of Marmara. Captives were taken and sold in the city as slaves. ‘And from this the Turks were roused to great anger against the Greeks, and swore that they would bring misfortune on them.’

The only other bright spot for Constantine during this period was the arrival of a straggle of Italian ships that he was able to persuade – or forcibly detain – to take part in the city’s defence. On 2 December a large Venetian transport galley from Kaffa on the Black Sea, under the command of one Giacomo Coco, managed to trick its way past the guns at the Throat Cutter by pretending that it had already paid its customs dues further upstream. As it approached the castle the men on board began to salute the Ottoman gunners ‘as friends, greeting them and sounding the trumpets and making cheerful sounds. And by the third salute that our men made, they had got away from the castle, and the water took them on towards Constantinople.’ At the same time news of the true state of affairs had reached the Venetians and Genoese from their representatives in the city and the Republics stirred themselves into tardy activity. After the sinking of Rizzo’s ship, the Venetian Senate ordered its Vice-captain of the Gulf, Gabriel Trevisano, to Constantinople to accompany its merchant convoys back from the Black Sea. Among the Venetians who came at this time was one Nicolo Barbaro, a ship’s doctor, who was to write the most lucid diary of the months ahead.

Within the Venetian colony in the city, concern was growing. The Venetian bailey, Minotto, an enterprising and resolute man, was desperate to keep three great merchant galleys and Trevisano’s two light

galleys for the defence of the city. At a meeting with the emperor, Trevisano and the other captains on 14 December he begged them to stay ‘firstly for the love of God, then for the honour of Christianity and the honour of our Signoria of Venice’. After lengthy negotiations the ships’ masters, to their credit, agreed to remain, though not without considerable wrangling over whether they could have their cargo on board or should keep it in the city as surety of their good faith. Constantine was suspicious that once the cargo was loaded, the masters would depart; it was only after swearing to the emperor personally that they were allowed to load their bales of silk, copper, wax and other stuffs. Constantine’s fears were not unfounded: on the night of 26 February one of the Venetian ships and six from the city of Candia on Crete slipped their anchors and fled before a stiff north-easterly wind. ‘With these ships there escaped many persons of substance, about 700 in all, and these ships got safely away to Tenedos, without being captured by the Turkish armada.’

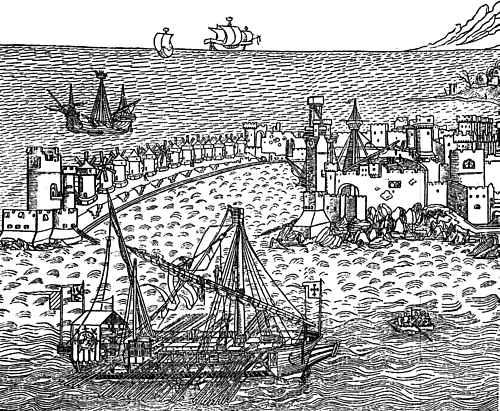

A Venetian great galley, the bulk carriers of the Mediterranean

This dispiriting event was offset by one other positive contribution. The appeals of the Genoese podesta at Galata had elicited a concrete offer of help. On about 26 January two large galleons arrived loaded ‘with many excellent devices and machines for war, and outstanding soldiers, who were both brave and confident’. The spectacle of these ships entering the imperial harbour with ‘four hundred men in full armour’ on deck made an immediate impression on both the populace and the emperor. Their leader was a professional soldier connected to one of the great families of the republic, Giovanni Giustiniani Longo, a highly experienced commander who had prepared this expedition at his own initiative and cost. He brought 700 well-armed men in all, 400 recruited from Genoa, another 300 from Rhodes and the Genoese island of Chios, the power base of the Giustiniani family. Constantine was quick to realize the value of this man and offered him the island of Lemnos if the Ottoman menace should be repulsed. Giustiniani was to play a fateful role in the defence of the city in the weeks ahead. A straggle of other soldiers came. Three Genoese brothers, Antonio, Paolo and Troilo Bocchiardo brought a small band of men. The Catalans supplied a contingent and a Castilian nobleman, Don Francisco of Toledo, answered the call. Otherwise the appeal to Christendom had brought nothing but disharmony. A sense of betrayal ran through the city. ‘We had received as much aid from Rome as had been sent to us by the sultan of Cairo,’ George Sphrantzes recalled bitterly.

5 The Dark Church

1

‘It is far better …’, quoted Mijatovich, p. 17

2

‘Flee from …’, quoted in an article on the

Daily Telegraph

website, 4 May 2001

3

‘Let God look and judge’, quoted Ware, p. 43

4

‘over all the earth …’, quoted ibid., p. 53

5

‘an example of perdition …’, quoted Clark, p. 27

6

‘a difference of dogma …’, quoted Norwich, vol. 3, p. 184

7

‘Whenever the Turks …’, quoted Mijatovich, pp. 24–5

8

‘the wolf, the destroyer’, quoted Gill, p. 381

9

‘If you, with your nobles …’, quoted Runciman,

The Fall of

Constantinople,

pp. 63–4

10

‘Constantine Palaiologus …’, quoted Nicol,

The Immortal Emperor

, p. 58

11

‘apart from …’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 1, p. 125

12

‘We don’t want …’, quoted Gill, p. 384

13

‘with the greatest solemnity…’, Pertusi,

La Caduta

, vol. 1, p. 11

14

‘the whole of the city …’, ibid., p. 92

15

‘nothing better than …’, quoted Stacton, p. 165

16

‘like the whole heaven …’, quoted Sherrard, p. 34

17

‘Wretched Romans …’, Doukas,

Fragmenta,

p. 254

18

‘has not stopped marching …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli

, p. 30

19

‘without it … on this very account’, Kritovoulos,

History of Mehmet

, pp. 29–31

20

‘We must spare nothing …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli

, p. 32

21

‘unusual and strange …’, ibid., p. 37

22

‘wheat, wine, olive oil …’, Doukas,

Fragmenta

, p. 257

23

‘And from this …’, Barbaro,

Giornale,

p. 3

24

‘as friends, greeting them …’, ibid., p. 4

25

‘firstly for the love of God …’, ibid., p. 5

26

‘With these ships …’, ibid., p. 13

27

‘with many excellent devices …’, Doukas,

Fragmenta

, p. 265

28

‘four hundred men …’, Kritovoulos,

History of Mehmed,

p. 39

29

‘We received as much …’, Sphrantzes, trans. Philippides, p 72

JANUARY

–FEBRUARY

1453

From the flaming and flashing of certain igneous mixtures and the terror inspired by their noise, wonderful consequences ensue which no-one can guard against or endure … when a quantity of this powder, no bigger than a man’s finger, be wrapped up in a piece of parchment and ignited, it explodes with a blinding flash and a stunning noise. If a larger quantity were used, or the case were made of some more solid material, the explosion would be much more violent and the flash and noise altogether unbearable.

Roger Bacon, thirteenth-century English monk, on the effects of gunpowder