Contested Will (19 page)

Authors: James Shapiro

After dinner that first evening Macy announced that he had brought along galley proofs of a forthcoming book, written by an English friend, William Stone Booth, called

Some Acrostic Signatures of Francis Bacon

. Isabel Lyon observed that âthe King was instantly alert'. The following day the conversation returned to the authorship question and Macy announced that Booth had found in every one of the plays published in the First Folio an acrostic, hidden there by Francis Bacon. To prove the point, he pulled out some page proofs and showed the ciphers to Twain, including one from the closing lines of

The Tempest

, where Booth had underlined a dozen key words in the facsimile of Prospero's Epilogue as they appeared in the 1623 Folio. Booth believed that the hidden signature in this play was especially convincing, coming as it did from the play's closing lines, âthe playwright's last word to his audience, and the place where he would be likely to sign his name in cipher if writing either under a pseudonym or anonymously'.

Macy couldn't have chosen a better example to pique Twain's interest â or indeed that of most admirers of Shakespeare's works at the time, since Prospero's departure from the stage was nearly universally read as Shakespeare's own, the most transparently autobiographical moment in the canon. Twain had trouble identifying Booth's seemingly random string cipher. With Macy's help,

he was finally able to follow it from the bottom of the page to the top, singling out the first letter of each key word and successfully spelling out the encoded signature: âFRANCISCO BACONO'. Macy confidently announced that Booth's book was âgoing to make a complete establishment of the fact that Shakespeare never wrote the plays attributed to him'.

*

Those quick to dismiss the possibility that a hidden acrostic signature could be overlooked for centuries may be unaware that a leading scholar had made such a find in a canonical work just a few years before Booth had begun his search.

The Testament of Love

was a medieval prose narrative that had been accepted without question as Chaucer's â by the likes of Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden and Coleridge â since its inclusion in the 1532 edition of his collected works. By the early nineteenth century, biographers such as William Godwin were drawing on key details in

The Testament of Love

to flesh out their story of Chaucer's life. Then, in 1897, while freshly editing this work, Cambridge professor Walter Skeat discovered that the first letter of the first word of each chapter formed an acrostic that spelled out: âMARGARETE: OF VIRTW, HAVE MERCI ON THSKNVI.' âMargaret of virtue, have mercy' made sense enough to Skeat, but who was âThsknui'? The puzzle was solved by his friend Henry Bradley, who pointed out that the order of the closing chapters had been rearranged. The acrostic originally read âTHIN VSK' â âthine Usk.' After three and a half centuries of false attribution,

The Testament of Love

was at last revealed to have been written not by Chaucer but by his fellow writer and admirer Thomas Usk. If one of Chaucer's works was now shown to have been written by somebody else, why not one or more of Shakespeare's?

A fierce race was on to see who would be the first to prove that Bacon's authorship was encoded in Shakespeare's plays. Booth was a relative newcomer to the contest; his formidable competitors and their teams of assistants had already devoted years of their lives to scanning Folio pages for word ciphers and biliteral ciphers.

By 1909 two of Booth's main rivals had already sailed to England, convinced they were on the verge of finding Bacon's long-buried manuscripts of the plays. For those invested in the authorship question, the excitement was intense. In July 1909, the official Baconian journal,

Baconiana

, excitedly announced âThe Goal in Sight' and held up publication through the autumn to be the first to break the news of the great discovery.

It was Delia Bacon's friend Samuel Morse who had set in motion the age's fascination with codes and ciphers. The effect of the telegraph and Morse code, not only on the popular appreciation of encryption, but also on how knowledge was now imagined as an act of decoding, was profound. Even as readers were searching texts for encoded clues, writers like Edgar Allan Poe (in stories like âThe Gold Bug') were beginning to produce fiction that turned on deciphering codes. At a moment when even children could send coded messages and governments and businesses regularly encrypted communications, the notion that earlier writers had hidden codes in their works no longer seemed far-fetched. And as the world-wide popularity of

The Da Vinci Code

attests, these Victorian assumptions have, if anything, become more deeply entrenched.

A few years after Mark Twain established the publishing house of Charles L. Webster and Company in 1884 he had a chance to publish what promised to be the definitive deciphering of Shakespeare's works. Its author, Ignatius Donnelly â former Lieutenant Governor of Minnesota, then three-term congressman, and a lifelong political reformer â had already won a wide following as a writer with his wildly popular

Atlantis: The Antediluvian World

in 1882, in which he argued that there really had been a lost world of Atlantis hinted at by the ancients. Donnelly followed up that success a year later with

Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel

, which claimed that a great comet had

smashed into the Earth aeons ago, almost destroying the planet. Even before these books came out, Donnelly had turned to a new project: âI have been working ⦠at what I think is a great discovery,' he wrote in his diary, âa cipher in Shakespeare's Plays ⦠asserting Francis Bacon's authorship of the plays ⦠I am certain there is a cipher there and I think I have the key.' It took Donnelly six years of exhausting labour to work out the code and publish his findings in the thousand-page

The Great Cryptogram: Francis Bacon's Cipher in the So-Called Shakespeare Plays

(1888).

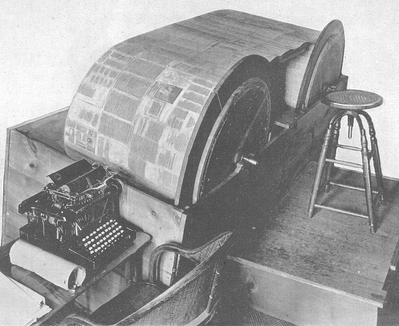

Cipher Wheel, frontispiece to vol. 2 of Orville Ward Owen's

Sir Francis

Bacon's Cipher Story

(Detroit, 1894)

Twain later recalled that when âIgnatius Donnelly's book came out, eighteen or twenty years ago, I not only published it, but read it'. That's not quite true. Twain had initially decided against taking it on, but then changed his mind and condemned his partner for failing to publish it. Twain had read Donnelly's book closely and found it âan ingenious piece of work'. In the end, though, he didn't find the acrostics convincing enough: âa person had to work his imagination rather hard sometimes if he wanted to believe inÂ

the acrostics', and, as a result, the book âfell pretty flat'. But Twain heartily endorsed Donnelly's argument that writers drew upon what they experienced first-hand, not what âthey only know about by hearsay'.

Donnelly had stumbled onto the authorship question by accident. Flipping through the pages of a volume his son was reading â

Every Boy's Book

â he came across a chapter on cryptography, where he learned that the âmost famous and complex cipher perhaps ever written was by Lord Bacon'. What âfollowed, like a flash' for Donnelly was the question: âCould Lord Bacon have put a cipher in the plays?' He immediately turned to Bacon's late work,

De Augmentis Scientiarum

, to learn more about Baconian ciphers, and was hooked. It didn't take long for Donnelly to conclude that Bacon had embedded âin the plays a cipher story, to be read when the tempest that was about to assail civilization had passed away'. The story was already taking on the apocalyptic dimensions of Atlantis and Ragnarok. Donnelly supposed that if Bacon had encoded a message, it would read along the lines of âI, Francis Bacon, of St. Albans, son of Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal of England, wrote these Plays, which go by the name of William Shakespeare.' Lacking a concordance, he set about reading through the complete works in search of something like it.

Having come up empty-handed, Donnelly decided that the encoding must have been far more sophisticated, so complex that Bacon had to have written the code first and the plays almost as an afterthought. As he later explained:

before Francis Bacon put pen to paper to write these plays, he had mapped out the cipher story; and had his pages blocked off in little squares, each square numbered according to its place from the top to the bottom of the page. He next adjusted the length of his columns, and their subdivisions, to enable him to pursue significant words like âwritten,' âplayes,' âshakst,' âspur,' etc., over and over again, and when all this was in place, he proceeded to write out the plays; using his miraculous ingenuity to bring the right words in the proper positions.

Donnelly didn't have a clue about how compositors worked in Elizabethan printing houses, where such a scheme would have been unimaginable and the layout he describes impossible to reproduce. Even with his complex arithmetical scheme, Donnelly had to fudge his word cipher, which was based on the numerical distance between his arbitrarily chosen key words. Worse still, he constantly miscounted in order to arrive at satisfying results. Cryptologists who have examined his method have concluded that he âdescribed Bacon's own cipher without understanding it' and âshowed a fatal inclination to seize on whole words which happen to be in both the vehicle and the message to be deciphered'. It also turned out that his cipher could produce virtually any message one wanted to find. Donnelly nevertheless remained confident âbeyond a doubt' that âthere is a Cipher in the so-called Shakespeare Plays. The proofs are cumulative. I have shown a thousand of them.'

Donnelly is notable less for his cryptographic skills than for his belief that there was a grander, autobiographical story buried in the plays. He saw, especially in

The Tempest

, a self-portrait of âthe princely, benevolent and magnanimous' Francis Bacon, who, âlike Prospero, had been cast down'. What began with a disguised author's hidden life blossomed into far-reaching and revisionist history: âthe inner story in the plays', Donnelly writes, makes visible âthe struggles of factions in the courts; the interior view of the birth of religions; the first colonization of the American continent, in which Bacon took an active part, and something of which is hidden in

The Tempest

'.

In the end, finding a disguised signature or an embedded autobiography or even rewriting world history wasn't enough, not for Donnelly and not for most cipher hunters. Like many other doubters, he went in search of that Holy Grail, the lost manuscripts of the plays. He suspected that they were âburied probably in the earth, or in a vault of masonry, a great iron or brass coffer'. While promoting his book in England he tried and failed to persuade the Earl of Verulam, Bacon's descendant, to allow him to

excavate at the estate in hopes of unearthing the long-lost manuscripts, following hints in the cipher.

We can smile at all this now, but in his own day, Donnelly's work won many admirers, among them the poet Walt Whitman, who recommended the book to friends and was inspired by it to write a brief poem â âShakespeare Bacon's Cipher' â later included in his

Leaves of Grass

:

I doubt it not â then more, far more;

In each old song bequeathed â in every noble page or text,

(Different â something unrecked before â some unsuspected author,)

In every object, mountain, tree, and star â in every birth and life,

As part of each â evolved from each â meaning, behind the ostent,

A mystic cipher waits infolded.

The poem initially bore the subtitle âA Hint to Scientists'. For Whitman, there was something not dreamt of in the philosophy of those supposed experts; he found deeply appealing the idea of a hidden, mystical meaning in all things, in all poetry â unseen by the rigid and doctrinaire.

Twain, too, was inspired by Donnelly's approach, enough to try his own hand at deciphering a literary work that had long fascinated him: John Bunyan's 1678 classic,

The Pilgrim's Progress

â though he never developed these ideas beyond a notebook sketch. Even as Donnelly and others had been troubled by the fit between the provincial man from Stratford and the greatness of the plays attributed to him, Twain became convinced that

The Pilgrim's Progress

could never have been written by someone with Bunyan's limited life experience. Twain concluded that

The Pilgrim's Progress

, with its account of the âEternal City', could only have been written by somebody who had actually been to Rome; Bunyan, who Twain joked, had never seen âanything but a canal boat', assuredly hadn't. So Twain reassigned the work to a writer he knew had travelled widely, John Milton, whose âgreat Continental Tour enabled him to imagine the travel in the Dream â and no stay-at-home could ever have done it'. Milton, Twain

added, âwas a clandestine duck' who âused to always jerk a public poem to divert attention from what he meant to do some day' in

The Pilgrim's Progress

; ânot knowing' that Milton âwas riddling', readers âtook him at his word' and misread his intentions. Once down the conspiratorial road, it was hard to stop. Twain also suspected that Milton also became involved in the Shakespeare conspiracy, and supposed that the âfurtive Bacon got him and Ben Jonson to play into his hand', persuading Milton to contribute an enthusiastic poem on âShakespeare' for the 1632 Second Folio. Knowing and admiring âBacon's secret', Twain writes, Milton âafterward borrowed the idea without credit'. As tempting as it is to dismiss this sketch as a parody on Twain's part, he seems far too invested, researched it too thoroughly and draws too many connections for it to simply be a joke:

The Pilgrim's Progress

, he concludes, âmust be read between the lines'. âThis has never been suspected before,' he concludes, but âthe cipher makes it plain'.