Cop Out (32 page)

Never had I seen a file drawer left open, papers piled on the desk, as much as a dust ball on the floor. Even after we had searched the files and the lab tech left a film of print dust on every surface, the room was still tidy. Now file cabinets were toppled, desk drawers yanked open, and Ott’s mustard-colored Naugahyde chair had been slashed in the few places where it wasn’t already taped together.

On the seat was a dead pigeon.

I found Ott curled up in a yellow wad on the backseat of Emma, the Studebaker. He probably hadn’t been asleep for more than a couple of hours. Exhausted, probably. I banged loud on the window.

Limp blond strands were matted to his forehead. His round, sallow cheeks were wrinkled from sleep. As his hazel eyes opened, his thin lips automatically curled.

Before he could greet me with his customary snarl, I said, “You owe me big time!”

He closed his eyes.

I banged the window so hard I thought it would break. “So, Ott, your friends—the Angels of Righteousness—trashed your office. What are you going to do, call the police?”

His eyes snapped open, and he was halfway to sitting up before he realized how much he’d given away.

So he hadn’t seen it. He’d just anticipated the danger.

“God damn it, Ott, if you had just told me about Cyril and the pesticide when you called me up to the Claremont—”

He mumbled something through the closed window.

“What?” I shouted, giving the window another bang.

He rolled it down an inch. “Couldn’t,” he mumbled.

“You couldn’t?” I screamed. “Why the hell couldn’t you?” Behind me in the apartment building a window opened. A guy shouted. I ignored him. “Why, Ott?”

“Because, Smith, I wasn’t going to leave you that bombshell.”

“

Leave

…” I could have wrung the rest of the explanation from him, but I knew him too well to bother. I shook my head. “It’s like Leonard said, we’ve all got our price. Ott, I thought yours was protecting your people. I was wrong, huh? You knew about the toxins. You weren’t about to tell the police at a time when you wouldn’t be around to monitor us as we investigated. And you couldn’t do that Sunday night, could you? Because between the time you called me and the time you got to the Claremont, Margo Roehner told you about the yellow-billed loon sighting.”

Ott’s lips pursed so tight he looked as if he’d swallowed his mouth. “Get out!” he growled, overlooking the fact that I was already out.

I went on. “And so you spent a night in the sand looking for the yellow-billed loon. And where is that loon? That loon, Ott, is where it always is: in Alaska.”

Ott’s face flushed pink. He shoved himself up higher on the seat and leaned toward me. “Get…”

“Ott, I took a lot of shit because I believed in you. No one else even entertained the idea that you might be innocent. Because of me, you are sitting in your own car instead of on a jail slab!”

He gave an odd little bouncy movement with his low sloped shoulder—his version of a shrug—and said the last thing I expected from him. “You’re right.” Then, as if the admission amazed him as much as it did me, he added, “You’re not a cop anymore; what is it you want from me?”

I stood there at the carport, staring blankly into the Studebaker. It didn’t surprise me that Ott knew I’d been suspended. It just shocked me to hear the words, to realize that I was no longer a police officer.

“Nothing, Ott. There’s nothing you can give me.” I turned and walked back to my Volkswagen bug and sat in the driver’s seat, feeling the closeness of the little car, the silence without the dispatcher’s voice sending out patrol officers, tracking chases, without the little give-and-take of those in the know. Suddenly I longed to banter with Eggs and Jackson, to watch Inspector Doyle shepherd his rhino herd to the side of his desk. I longed for Pereira to gobble down the rest of my scone before I had decided I was full. I longed for Howard. Oh, god, Howard.

A whirling cold emptiness expanded within me.

It would have been easy to “get” Ott, with a comment about his chauffeured ride to Kennedy Airport or a comment on his father. But like him, I have principles. I will never mention the Hermans and the Otts of Pittsburgh, nor think of him without picturing the smiling little running back on the Monongahela Mongeese team.

And I will never ask Daisy Culligan if it was Herman Ott who suggested her clever tat against Bryant Hemming. He merely wanted to know what was in the ACC books he couldn’t get at. Even Ott couldn’t have foreseen that it would lead to Bryant Hemming’s murder and Margo Roehner’s destruction.

The fog had thinned to that gauzy gray that makes the hills look Japanese and promises hidden spots of beauty and silence. I drove slowly west toward Howard’s house; I was almost to Ashby Avenue before I shifted out of second. The sky was the same murky battleship color that pales the orange and vermilion leaves. It wasn’t till I saw the looming brown shingle and the empty driveway that I realized I wasn’t ready to see Howard.

I drove on to Ashby Avenue and stopped at the corner. I could turn right and right again at the freeway, as Charles Edward Kidd would have done if he’d owned a car. As my great-uncle Jack’s neighbor Mrs. Bronfmann had done that day when she’d climbed onto the crosstown bus and the Spanish exchange student had caught her eye. As Howard’s mother had whenever hope or terror or maybe whim had teased her forward.

I’ve thought of the contrast between Howard’s mother and mine. My mother spent her life clutching on to the small acorn of security she could find in each new house and town to which her dreamer of a husband led her, putting her best foot forward toward the neighbors as if this house or job would be the one that would take root. She clung to her hope against the sea of fact and fear and common sense that surrounded her. Howard’s mother floated above it all. When I’d last visited my parents in their retirement apartment in Florida, their days were filled with golf and bridge, their nights thick with the fear that inflation would make their payments too steep. My mother cashes the checks I send, but I doubt she spends them. And Howard’s mother, Selena Bly, is she worse off? I sometimes wonder when they land in their final places if there will be a hairsbreadth of difference between them.

I turned right, up Ashby, away from the freeway. Spikes of sun pierced the fog and glistened off the Claremont Hotel’s white turret. I hung a left and wound up into the hills till I came to a pullout on Grizzly Peak. I opened the door of my familiar little car, stepped out, and looked down at Berkeley from a different angle.

Susan Dunlap (b. 1943) is the author of more than twenty mystery novels and a founding member of Sisters in Crime, an organization that promotes women in the field of crime writing.

Born in New York City, Dunlap entered Bucknell University as a math major, but quickly switched to English. After earning a master’s degree in education from the University of North Carolina, she taught junior high before becoming a social worker. Her jobs took her all over the country, from Baltimore to New York and finally to Northern California, where many of her novels take place.

One night, while reading an Agatha Christie novel, Dunlap told her husband that she thought she could write mysteries. When he asked her to prove it, she accepted the challenge. Dunlap wrote in her spare time, completing six manuscripts before selling her first book,

Karma

(1981), which began a ten-book series about brash Berkeley cop Jill Smith.

After selling her second novel, Dunlap quit her job to write fulltime. While penning the Jill Smith mysteries, she also wrote three novels about utility-meter-reading amateur sleuth Vejay Haskell. In 1989, she published

Pious Deception

, the first in a series starring former medical examiner Kiernan O’Shaughnessy. To research the O’Shaughnessy and Smith series, Dunlap rode along with police officers, attended autopsies, and spent ten weeks studying the daily operations of the Berkeley Police Department.

Dunlap concluded the Smith series with

Cop Out

(1997). In 2006 she published

A Single Eye

, her first mystery featuring Darcy Lott, a Zen Buddhist stuntwoman. Her most recent novel is

No Footprints

(2012), the fifth in the Darcy Lott series.

In addition to writing, Dunlap has taught yoga and worked for a private investigator on death penalty defense cases and as a paralegal. In 1986, she helped found Sisters in Crime, an organization that supports women in the field of mystery writing. She lives and writes near San Francisco.

Dunlap and her father at the beach, probably Coney Island. ”“My happiest vacations were at the beach,” says Dunlap, “here, at the Jersey shore, at Jones Beach, and two glorious winter weeks in Florida.”

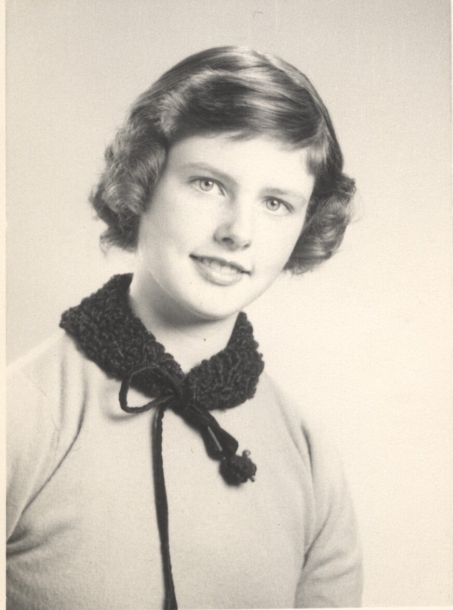

Dunlap’s grammar school graduation from Stewart School on Long Island, New York.

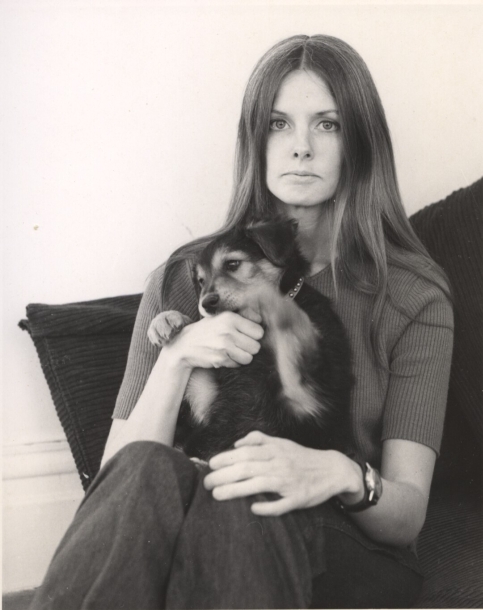

In 1968, Dunlap arrived in San Francisco; this photo was taken by her husband-to-be atop one of the city’s many hills. Dunlap recalls, “It’s winter; I’m wearing a T-shirt; I’m ecstatic!”

Dunlap’s dog Seumas at eight weeks old. “We’d had him two weeks and he was already in charge, happily biting my hand (see my grimace),” she says. “He lived for sixteen good, well-tended years.”

Dunlap started practicing yoga in 1969 and received her instructor certification in 1981, after a three-week intensive course in India with B. K. S. Iyengar. Here she demonstrates the

uttanasa

pose (the basic standing forward bend) for her students.