Counternarratives (3 page)

Authors: John Keene

Meanwhile, Fonte da Ré's replacement, Nogueira, had reassigned most of

Londônia's men to Viana's regiment, now reconstituted as part of a larger military

unit which was to take up a position north of Olinda, close to the Dutch fort at

Itamaracá. Capturing the fort would, Nogueira's superiors thought, prove decisive.

Though Viana hoped that the tribunal would rule swiftly on what was by now an

oft-mentioned punch line of his infamous humiliation (“tied up by that crazy nigger

Figueiras, no less!”), there was a war to wage. The men shipped out on a navy vessel

from the deep harbor at Salvador on the day the trial began; the winds were in their

favor and only a short while later they had anchored off the coast of Pernambuco, as

the general in charge deliberated on their plans.

Viana's lawyer, seeking to have him testify, learned that he had

been mustered out. An order must be issued not to send him into battle; his case was

underway. His commander, Nogueira, for his part, had not received word of the trial,

though it was taking place on the other side of the garrison. The lawyer requested a

stay, until he might present further testimony. The tribunal, however, wanted to

conclude the trial as soon as possible, as it was, by any measure, a distractionâthe

officers were needed for the ongoing campaign, and there were pressures from other

quarters, in any case. Several of Londônia's menâDos Santos, Pereiraâtestified: they

were rough-hewn characters, not entirely reliable, the members of the tribune

conceded, but their tales of their commander's determination and valor would have

persuaded the devil. Viana's lawyer elicited no counter claims; he returned to studying

his written commentary. Again, he requested an appeal to be delivered to Nogueira,

then rested his case.

Londônia sat to testify. The panel found his narration of heroism during

the earlier Bahian conflict, followed by his campaign in the wilderness,

enthralling. There was so much to hear, those Figueirases have a way with the word.

Despite the seriousness of the affair, a current of easy familiarity passed among

the men. Several laughed at Londônia's account of the circular march through the

jungle; his route, he suggested to them, would eventually make a fine cow path.

There were those Indians, of course, and other hardships, which need not be

elaborated upon. He was no Jesuit, mind you. All he had to show for his exertions,

however, was the unmistakable burnt-cork tan from wandering in the sun and forest

for so long, and an amulet, which his councilor requested be entered into the

record. Londônia even mentioned that he would have brought them back his pet monkey

to exonerate him, only he'd forgotten it in his parents' home in Sergipe. When the

session concluded, several of them thought he ought to be promoted on the spot,

until they were reminded of the full slate of charges against him.

Back in Pernambuco the order came: Viana and his men boarded and

launched small craft to reach the shore. The Dutch, surprised at the gross lack of

subtlety, began their fusillade. The cannons at the fort let loose, while

sharpshooters took aim, supplemented by a team of archers. Whatever men were not

drowned and made it to shore fell quickly to the sandsâViana, who had never set foot

on Pernambucan soil, was at least able to register this new achievement momentarily

before closing his eyes for the final time.

Back in Bahia, the military lawyer waited; still no Viana. Nor did any

other witnesses come forward. The head of the tribunal was losing patience; was this

Viana unaware that the Dutch held territory as far north as Rio Grande do Norte?

Things proceeded, arguments. . . . The councilor gave his final plea on behalf of

the hero, which stirred nearly all present. Then the military lawyer spoke, so

rapidly one had to strain to hear him. Arguments ended, the panel ruled. Londônia

had grounds, there was the necessity of following his orders and the insult, so he

would keep his commission, but he would be assigned, at least for a while, in a

training capacity to a garrison near the city of Rio de Janeiro. Until such time, he

should relax and reacquaint himself with civilization. All shook hands, the Colonel

was released. Several slaves carried his numerous effects to his sister and

brother-in-law's home, in the upper city above the Church of the Bonfim, where he

would lodge until he set sail for Rio. Friends of the family paid visits; in his

honor Mrs. Figueiras Henriques threw a sought-after farewell dinner, which concluded

in dawn revels.

The journey to Rio was an unpleasant one, though Londônia had his

comforts. From the ship, he could see that this second city, on the Guanabara Bay,

was, despite its mythical mountains and bristling flora, markedly more rustic than

the capital. But he had grown up on a sugar estate, far from the poles of

civilization, and could adapt. As Londônia walked through the port area to hire a

horse to reach the garrison, he found himself in the midst of a public scene. There

was shouting, shrieks; a shoeless mulatto, his face and shirt and breeches clad in

blood, scampered past him, followed by a large slave woman sporting a bell of

petticoats, screaming. What on earth was this? Then another man, short, emaciated,

with the sun-burnt face of a recently arrived Portuguese, emerged from the wall of

bodies, his right hand thrusting forward a long dagger. Londônia tried to slip out

of the way and brandish his sword in defense, but his reflexes, dulled after the

protracted incarceration, failed him.

As soon as word reached the military officials in Bahia, he received

several raises in rank; his body was brought back to Sergipe d'El Rei for a proper

funeral. An auxiliary bishop officiated at the burial. It was only several months

later that his wife, who had given birth and returned to her parents' home, learned

of her husband's misfortune. She was now a wealthy woman.

Th

eir son, whom she originally named Augusto, was henceforth known as

Augusto Inocêncio. She soon remarried, producing several more sons and daughters,

and resettled with her new husband, a soldier who was related on his maternal side

to the Figueiras family, near the distant and isolated village of São Paulo.

On Dénouement

I

n 1966, the

model Francesca Josefina Schweisser Figueiras, daughter of army chief General Adolfo

Schweisser and the socialite Mariana Augusta “Gugu” Figueiras Figueiras, married

Albertino Maluuf, the playboy son of the industrialist Hakim Alberto Maluuf, in a

lavish ceremony in the resort town of Campos do Jordão. The event, conducted by His

Eminence, the cardinal, in the Igreja Matriz de Santa Terezinha, with a reception on

the grounds of the newly inaugurated Tudor-style Palácio Boa Vista, was covered in

society pages across the Americas and Europe. They were divorced shortly after the

country's return to democracy two decades later, in 1987.

Their youngest son, Sergio Albertino, was known as “Inocêncio,” a family

nickname given, for as far back as anyone could recall, to at least one of the

Figueiras boys in each generation. Sergio Albertino's marked simplicity of

expression and introverted manner confirmed the aptness of this name, by which he

quickly and widely became known. Yet from childhood this same Inocêncioâ“emerald

eyes, skin white as moonstone, a swan's neckӉalso periodically exhibited willful,

sometimes reckless behavior, engaging in fights with other children, committing acts

of vandalism, setting fire to a coach house on the family's estate that housed the

cleaning staff. He met with numerous and repeated difficulties in his educational

progress. No tutor his mother enlisted lasted longer than a few months. Bouncing

between boarding schools in the United States, Switzerland, Argentina, and Brazil,

he developed a serious addiction to heroin and other illicit substances. An

encounter with angel dust at a party thrown by friends in Iguatemà led him to drive

a brand-new Mercedes coupe off an overpass, but he was so intoxicated that he

suffered only minor injuries. After a short involvement with a local neo-Nazi group

and repeated stays in rehabilitation centers, he dropped out of Mackenzie

Presbyterian University, in São Paulo, where he had enrolled to study business, a

profession which his family had long dominated. An arrest for possession of ten

grams of cocaine, a tin of marijuana and three Ecstasy tabs led to a suspended

sentence. His community service included working with less fortunate fellow addicts

in other parts of the city. Quickly befriending several of these individualsâfriends

of his parents remarked in the most restrained manner possible that from childhood

the boy had possessed uncouth predilections and tastesâhe increasingly spent time in

city neighborhoods in which most people of his background, under no circumstance,

would dare set foot. The bodyguards his parents hired gave up trying to keep track

of him. One evening in midsummer, he left the flophouseâwhere he was staying with a

woman he'd met on a bingeâto score a hit. . . .

Â

“Oh, this terrible ancient pain

we feel down to our bones

that fills the contours of our dreams

whenever we're aloneâ”

On Brazil

S

ão Paulo,

once a small settlement on the periphery of the Portuguese state, is now a vast

labyrinth of neighborhoods upon neighborhoods, a congested super-metropolis of

more than fourteen million people, the economic engine of Latin America. As Dr.

Arturo Figueiras Wernitzky has noted in his magisterial study of the region,

millions of poor Brazilians, many of them from the northeastern region of the

country, including the states of Bahia, Sergipe and Pernambuco, have migrated

over the last four decades to this great city, its districts and environs,

suburbs and exurbs, primarily in search of work and economic opportunities.

Among these

nordestino

migrants, many of them of African

ancestry, were members of the Londônia family from the towns of the same name in the

states of Bahia, Sergipe, and Pernambuco, who constructed and established

unauthorized settlements, or

favelas

, across the city of São Paulo, lacking

sewage and electricity, and marked by the highest per capita crime rates outside of

Rio de Janeiroâmurders, assaults, drug-dealing, and larceny, as well as

well-documented police violence.

Among the most notorious

favelas

is one of the newest, as yet

unnamed, only marked on maps by municipal authorities by the

letterâ

N

.âperhaps for “(Favela) NovÃsima” (Newest Favela), or “(Mais)

Notório” (Most Notorious), or “Nada Lugar” (No Place), though it is also known,

according to journalists and university researchers like Figueiras Wernitzky, who

are examining its residents as part of a larger study of demographic changes in the

region, among those who live in it, as “Quilombo Cesarão.”

AN OUTTAKE FROM THE

IDEOLOGICAL

ORIGINS OF THE

AMERICAN REVOLUTION

Origins

I

n January 1754, Mary,

a young Negro servant to Isaac Wantone, wealthy farmer and patriot of the town of

Roxbury, Massachusetts, gave birth in her master's stables to a male child. An older

Negro servant, named Lacy, also belonging to Wantone's retinue, attended Mary in her

prolonged and exacting labor, during which the slave girl developed an intense

fever. For an half-hour after Mary delivered the child, a tempest raged within her

as she lay screaming in a strange tongue, which was in part her native

Akan

. Then her eyes rolled back in her head and she expired. Lacy uttered a

benediction in that same language, and thereafter presented the infant to her

master, Mr. Wantone, as was the custom in those parts. When he saw the

copper-skinned newborn, eyes blazing, upon whom the darkness of Africa had not

completely left its indelible stamp, the master, adequately versed in the

Scriptures, promptly named him Zion, which in Hebrew means “sun.”

Knowing his servant not to have been married or even betrothed at the

time of the child's birth, Wantone rightly feared the sanctions laid down by Puritan

and colonial law, which in the case of illegitimate paternity included whippings,

fines rendered against the mother of the child, its father, and quite probably the

master, be he same or otherwise. Wantone also might have to put in an appearance

before the General Court. Though not a gentleman by birth (he was of yeoman stock

and self-read in the classics), Wantone had fought admirably among his fellows in

King George's War and had by dint of many years' toil built up an excellent estate.

Moreover, he subscribed unwaveringly to the Congregational Church. And, on all these

accounts, he declined to have his reputation or standing in the slightest besmirched

by such a scandal. He had therefore conspired to conceal Mary's condition for the

full length of her term by keeping her indoors as much as possible and forbidding

her to venture out near the local roads, where she might be spied by neighbors or

passersby. He also forbade his servants and children to speak of the matter, lest

their gossip betray him. Toward neither plan did he meet with rebellion; so it is

said that one's sense of the law, like one's concept of morality, originates in the

home. The child's father, whose name the taciturn girl had refused to speak, Wantone

identified as Zephyr, a sly black-Abenaki horsebreaker in the service of his

neighbor, Josiah Shapely. Among the members of his own household, however, he

himself was not entirely above suspicion, especially given the child's complexion.

In any case, Zion would, according to plan, officially be deemed a

foundling

.

Wantone's wife,

née

Comfort and descended from an

unbroken line of Berkshire Puritans who had arrived in the Bay Colony not long after

the Mayflower, had for several years been growing ever more austere in her faith,

and to the achievement of a glacial purity of relations. As a result she abhorred

all spiritual and fleshly transgressions, especially bastardy, in which the two were

so visibly commingled. Upon learning of the infant's imminent entry into the sphere

of her family's existence, she ordered that it be kept out of her sight altogether.

Music

W

hen Lacy had first

passed the infant Zion to her master for inspection, the child began to cry

uncontrollably. Wantone order him to be placed in a small wooden crib on the second

floor of the house above the buttery: thereby he might learn peace. This weeping,

which soon became a kind of keening, persisted for several weeks without relent.

Meanwhile Wantone ordered his slaves Jubal, a native-born Negro who tended his

livestock, and Axum, a young mulatto of New Hampshire origin who served as his

handyman, to bury the deceased slave girl Mary near the edge of his south grazing

fields. At her interment, the master recited over the grave a few lines from the Old

Testament, and wept.

Lacy was nearing middle age, yet this chain of events soon bound her

into assuming the role of the child's mother. Otherwise she was engaged in

innumerable chores about the house or attending to her mistress, Mrs. Wantone, who

did not like ever to be kept waiting. Lacy had not seen her own child since shortly

after his sixth birthday nearly fifteen years before, because her previous master,

then ill with cancer and disposing of his Boston estate, had sold the boy north to a

merchant in Newbury, and her south to Wantone. Taking frequent quick breaks, she

nursed the infant Zion from a suckling bottle, on warm goat's milk sweetened with

honey and dashes of rum, of which there was no shortage in the cellar. She also sang

to him the lively songs she remembered from her childhood along the lower Volta, in

the Gold Coast, as well as Christian hymns when any member of the family, especially

her mistress, was in earshot. Eventually the child calmed down appreciably, and

Wantone allowed him to be carried about the entire house and grounds when the

mistress was away.

Though these were years of increasing privation for many in the

Colony as the noose of the mother country tightened, Wantone prospered. Not long

after this time he purchased a likely young Negro woman, named Mary, for £11 from

the Boston trader Nicholas Marshall, to replace the deceased Mary, who had attended

primarily to the four Wantone children, Nathanael, Sarah, Elizabeth, and Hepzibah.

New Mary was also expected to afford Lacy more time for Mrs. Wantone by also

watching Zion. This became the only task to which she took with even a passing

enthusiasm. She had been born in the region of the Gambia, where all were free, and

quickly chafed under the weight of her new status. She ignored orders; she talked

back. Moreover she was given to spreading rumors and painting her face and fingers

gaily with Roxbury clay and indigo on the Sabbath, while declining to recite the

Lord's prayers, as well as to other acts of idleness, gossip, lewdness, and

truculence. For these offenses, to which the boy was a constant witness, she was

routinely whipped by her mistress, who took a firm and iron hand at all times.

Naturally, New Mary ran away, to Brookline, where she was captured by the local

constabulary, and returned bound to the Wantones. She received ten lashes for her

impertinence, another ten for her flight, still a third ten for cursing her mistress

before the other slaves, and an interdiction not to leave the grounds of the estate

under any circumstances. One can only temporarily keep a wild horse penned. For

several years, as the child Zion was nearing the age of his autonomy (seven), New

Mary endured these constraints, peaceably rearing the child with Lacy and the

several Negro male servants, Jubal, Axum and Quabina. And then she ran away again,

this time getting as far south as Stoughton, on the Neponsit River. Again she was

returned, duly punished, ordered to comport herself with the dignity befitting the

Wantone household. Repeated incidents of insolence and misbehavior followed,

however, including acts of a lascivious nature with a local Indian, the destruction

of several volumes of books, and an attempted fire. The Wantones sold New Mary to a

Plymouth candlemaker for £4. Zion was, for nearly a year, inconsolable.

Even during New Mary's tenure Zion had often shown signs of melancholy

or unprovoked anger. Frequently sullen, he would often sequester himself in the

buttery, or at the edge of the manor house's Chinese porch, singing to himself

lyrics improvised out of the air or songs he had learned from Lacy and the other

slaves. Or he would declaim passages from the local gazette which Axum or the

Wantone children had taught him. At other times he would devise elaborate counting

games, to the amazement of the other slaves. When caught in such idle pursuits on

numerous occasions by Mrs. Wantone, who spared no rod, he did not shed a tear. Her

punishments instead appeared only to inure him to discipline altogether. He began

singing more frequently, and would occasionally accompany his songs with taps and

foot-stamps. His master took a different tack, and hedgingly encouraged the boy in

his musical pursuits, so long as they did not disturb the household or occur on the

Sabbath. As a result the idling musical sessions abatedâtemporarily. Even so, Mrs.

Wantone relinquished Zion's correction to her husband and eldest son.

As soon as Zion was able he began performing small tasks about the

house and estate, such as restuffing the mattress ticks, mucking out the stables,

replacing the chamberpots, polishing the family's shoes, and feeding the hens. His

intermittent disappearances and musical-lyrical spells soon reappeared. At the age

of ten, he entered an apprenticeship to Jubal, and then at eleven to Ford, the

Irishman who oversaw the extensive Wantone holdings, which included twenty acres of

home lot, fifteen acres of mowing land, twelve and a half acres fifteen rods of

pasture land, twenty acres ten rods undivided of salt marsh, ten acres of woodland

and muddy pond woods to the south, and six acres of woodland to the west, all in

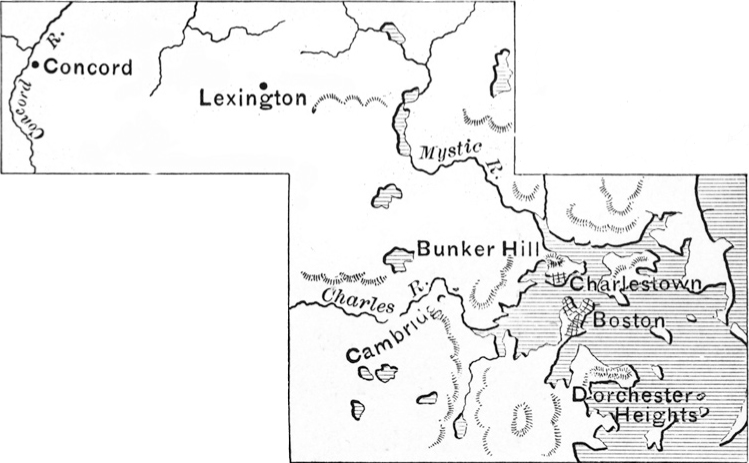

Roxbury and Dorchester; as well as a plot of forty acres of woodland in Cambridge,

recently bequeathed by his late brother-in-law, Nathanael Comfort, Esq., a graduate

of Harvard College and a gentleman lawyer. From Ford, Zion learned a number of Irish

melodies, which he performed to the delight of all on Negro Election Day and other

holidays. During the late summer evenings, he would accompany a nearby slave

fiddler, and soon developed a name throughout the neighborhood as a warbler.

One afternoon around the time of Zion's thirteenth year Jubal heard

fiddling out near the cow barn. On investigation, he found the boy creditably

playing his master's violin and singing a sorrowful tune in accompaniment. The

horses stood in their stables, unbrushed. Because he liked the saturnine child,

Jubal waited until Zion had finished his performance. After reproaching him, Jubal

seized the violin and returned it to the music room. When he returned to the barn,

the boy was missing. Several weeks later Jubal again found Zion playing the violin

in the afternoon, when he should have been at the chicken-coop feeding the hens;

this time he threatened to tell on the boy if he took the violin again, to which

Zion only laughed and dared Jubal to say anything. Jubal returned the violin without

incident. The third time Jubal encountered the boy fiddling in the barn, he rebuked

him vehemently, but before he could snatch away the violin, Zion smashed it to

smithereens on a trough. For this, he eventually received stripes from both his

master and his master's son, and a ban on singing of any sort. The boy's wild mood

swings and moroseness waxed from this point, to the extent that the other slaves,

particularly Jubal, took care not to offend him. Wantone himself remained

unconcerned, as he was the master of his manor, and an oak does not quiver before

ivy.

Around the time of his fourteenth birthday, Zion, now so strapping in

build and mature in mien that he could almost pass for a man, ran away for the first

time. Absconding in the dead of night, he got as far as the town of Dedham, some

nine miles away. There he remained in the surrounding woods undiscovered for a week,

until his nightly ballads and lamentations betrayed him to a local Indian, who

reported the melodiousness of the voice to the town sheriff. Returned to his master,

Zion received the following punishment: he was placed in stocks for a night, and

then confined to the grounds of the estate, with the threat that any further

misdeeds could result in his being temporarily remanded to the custody of the local

authorities. Within a fortnight the boy had run away again, this time with one of

Wantone's personal effects, and a pillowbeer of food. A search of the surrounding

towns turned up no clue of him. As a result, Wantone was forced to advertise in the

local gazette for the return of his lawful property.

Flight

From the

New England Weekly News Letter

, June 18,

1768:

Ran away from his master Isaac Wantone gentleman of the

country town of Roxbury in Suffolk County, in Massachusetts Bay Colony, a likely

Negro boy aged fourteene years, named

ZION

, who wore on

him [an] old grey shirt homespun and pair of breeches of the same cotton cloth, with

shoes only, and a kerchief about his head, carrying a silver watch, clever, who

sings like a nightingall:

WHO

shall take up said likely

ZION

and convey him to his

MASTER

above said, or advise him so that he may have him again shall be

PAID

for the

SAME

at the

rate of £4 1s.

To Pennyman

T

hree months

had advanced when the sheriff's office of the town of Monatomy, in Middlesex County,

returned to the Wantones the fugitive child, who had been arrested and detained on a

series of charges. These included but were not limited to breaking the Negro curfew

in Middlesex County; theft (of various small articles, including watches and food);

disturbance of the peace; brawling, gambling and trickery at games of chance;

dissembling about his identity and provenance; and masquerading as a free person.

Most seriously the young slave had beaten up an Irish laborer outside a public house

in Waltham, and threatened the man's life if he reported the beating to the

authorities, local or the King's. For this series of offenses, which broke the

patience of the Wantones, the General Court of Middlesex County arraigned, tried and

convicted the slave, to the penalty of thirty-five stripes, and a fine of £10,

payable to the victims. After the boy received his public lashes, his master settled

the fine and issued an apology for his slave's behavior to the General Court, which

was printed in all the local papers. He then promptly flogged Zion himself before

restraining the boy in a stock behind the cow barn. During this time, the Wantones

considered their options, and agreed it would be in their best interests to sell

their intractable chattel, who, they supposed, still had arson and murder waiting in

his kit. This they promptly did despite the rapidly deflating nature of the local

currency, for the sum of £5, to a distant relative of Wantone's, the merchant Jabez

Pennyman, then living on a small estate in the Dorchester Neck.