Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court (48 page)

Read Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #England, #History, #Royalty

Certainly the ministers and the politicians and the king’s constitutionally limited position intensified the trouble within his family, setting father against son with such hideous results. George II’s eldest son was still alienated (and still the focus for trouble-making Opposition politicians), while his daughters were now scattered to the foreign marriages dictated by international politics.

While the king’s power as a constitutional monarch may not have been unlimited, power it still was, and in reality it was very considerable in quantity. The twentieth-century historian Aubrey Newman established that George II’s political influence has been underestimated because of the way he dealt with his paperwork.

On one occasion when he was instructed to search the king’s desk, George II’s Lord Chamberlain made a strange discovery: ‘what is extraordinary, scarce any papers’. ‘The King never loved to keep any papers,’ he was told.

90

In fact, George II had the habit, when he received a letter, of scribbling notes and instructions in the margins

of the letter itself

and returning it to the sender. That’s why – unlike George III, for example – he amassed no great archive of correspondence. Most of his political interventions are scattered widely throughout the archives of his ministers and correspondents, often unrecognised by historians as royal letters at all.

91

Eighteenth-century commentators more kindly disposed towards the king noted that after a long apprenticeship, he was in fact getting better at business, and that ‘his observations, and replies to the notes of his ministers … prove good sense, judgement, and rectitude of intentions’.

92

After Caroline’s death he became increasingly hard-working. This was partly because his continued distance from his children and the loss of the social life that Caroline had organised left paperwork as ‘almost his only amusement’.

93

It was certainly a diligent king who was involved in one transaction tracked down by Aubrey Newman. An urgent letter was sent to the king by his Secretary of State:

I beg Your Majesty’s pardon for presuming to send the enclosed so blotted and interlined, but as Lord Chesterfield presses for an answer … I chose rather to send it in this condition than to lose time in having it written over.

George II, though, was well ahead of the game, answering gruffly that he had dealt with the matter the previous day. The implication was that his secretary should try harder to keep up to speed.

94

The king also retained more power over Parliament than one might think from his constant complaints. He could make the lives of his ministers miserable if they crossed him. As one of them complained, ‘no man can bear long, what I go through, every day, in our joint audiences in the closet’.

95

But then again, it has to be admitted that George II was simply not the brightest button in the box: he could comment ‘sensibly and justly on single propositions; but to analyse, separate, combine, and reduce to a point, complicated ones, was above his faculties’.

96

Despite his carefully cultivated attention to detail, he was trapped in a role that did not really suit him.

George II’s devotion to Hanover – and not just to the person of Amalie – remained strong and brought with it all kinds of trouble for Britain. The British found their position in European politics constantly compromised by Hanover’s needs. John Hervey thought it was dreadfully wrong that George II often made decisions as Elector of Hanover, when ‘his interest as King of England ought only to have been weighed’.

97

He would secretly negotiate, for example, to extricate the German state from continental conflicts without the knowledge of his British ministers.

98

As he grew older, the king still longed for the soldierly days of his youth. His sole pleasure as age came fast upon him was to dream nostalgic dreams of war and action. Battle, after all, had

been the only activity in which he’d excelled. Childlike, he still liked to dress in the hat and coat that he’d worn at the tremendous victory of Oudenarde in 1708 (his courtiers found it hard not to laugh at this).

99

He was often heard to say that he could hardly bear ‘the thought of growing old in peace, and rusting in the cabinet, while other princes were busied in war and shining in the field’.

100

This longing for action manifested itself in his keeping an encyclopaedic knowledge of all the officers in the army and participating enthusiastically in endless military reviews.

101

On one memorable, if deafening, occasion the king was saluted by ‘three running fires of the whole army from right to left’.

102

These great army set-piece occasions were fast losing any real relationship they may once have had with tactics upon the battlefield, but they were still an important display of military might, besides being good fun for everyone.

George II also had a thwarted soldier’s obsession with uniforms, and insisted that his colonels consult him upon their proposed designs for each regiment. And, in paying minute attention to matters of clothing, the king was acting as a true barometer of his age.

*

Out on the streets of London in 1742, the year of the battle of the mistresses, there was much evidence of an accelerating obsession with the stuff of fashion, with fabric and with furnishings.

The men and women strolling through St James’s Park were becoming ever more extravagantly dressed, ‘embroidered and bedawb’d as much as the

French

’.

103

A town lady sent a country cousin a bonnet with the warning: ‘don’t be frightened at its bigness, ’tis all the fashion … and what now every creature wears’.

104

The day dress for a young blade about town might by now have consisted of the frock coat, described as ‘a close body’d coat … with strait sleeves’.

105

He could choose from a cornucopia of euphoniously named wig styles: ‘Pidgeon’s wing, Comet, Cauliflower, Royal Bird, Staircase, Wild Boar’s Back, She-dragon,

Rose, Negligent, Cut Bob, Drop-wig, Snail Back, and Spinnage Seed’.

106

One extreme manifestation of 1740s fashion came in the form of the new ‘hoop-petticoats, narrow at the top, and monstrously wide at the bottom’.

107

Richard Campbell, author of

The London

Tradesman

, was quick to see their dual advantage: when they tipped up, they revealed the ‘secrets of the ladies’ legs, which we might have been ignorant of to eternity without their help’. Of more practical benefit, the demand they created for ‘whale bone renders them truly beneficial to our allies the

Dutch

’.

108

An enormous 20 per cent of London’s labour force was employed in the clothing industry.

At court, the archaic, other-worldly mantua was still the formal female dress, remaining obligatory for drawing-room evenings, coronations and royal weddings. The ordeal of wearing a mantua was more than familiar to Amalie von Wallmoden and Mary Deloraine, although people outside the palace walls had abandoned them long ago.

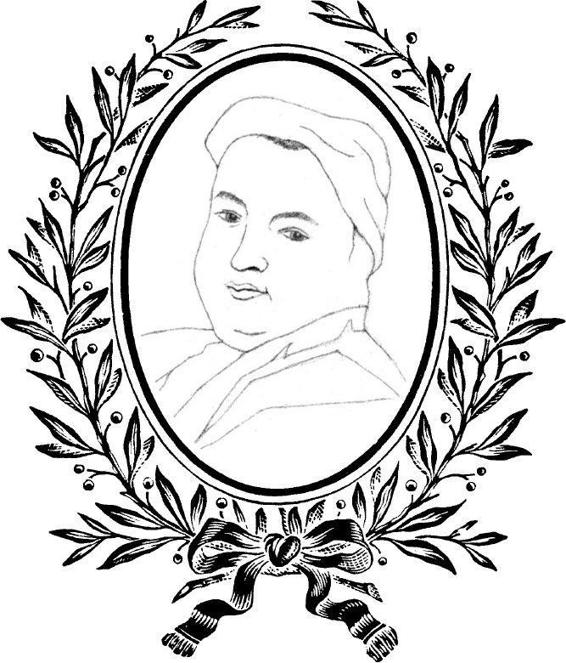

A court mantua. The dress itself weighed ten pounds (it was made of silver thread), while the whalebone hoops burdened the wearer with the same again in weight. No wonder ladies complained about the agony of wearing them

The immense cost of a mantua appropriate for George II’s drawing room lay in its expensive materials: silk and silver lace sold by weight. The cutting out and sewing of a gown cost less than 2 per cent of the total bill, and discarded dresses would sometimes be melted down to recover the precious metal. The dress Lady Huntingdon wore to Prince Frederick’s birthday celebration in 1738 nearly killed her with its metallic weight: she became ‘a mere shadow that tottered under every step she took under the load’.

109

While court fashions were antiquated and awkward, there was one new development: the mantua was gradually being ousted from pride of place by the hyper-elegant French alternative, which nevertheless went by the inelegant name of the ‘sacque’, or ‘sack’. Cut from just one piece of cloth, the sack featured the so-called ‘Watteau pleat’, a cascading pleat falling from the shoulders to the floor at the back. Seen on Jean-Antoine Watteau’s delicate painted ladies, it is ravishingly weird.

An obsession with fashion was a well-recognised eighteenthcentury affliction. It was mocked by Alexander Pope in his poem about the small-minded ‘Chloe’ and her preference for things rather than people:

She, while her lover pants upon her breast,

Can mark the figures on an Indian chest;

And when she sees her friend in deep despair,

Observes how much a chintz exceeds mohair.

110

The model that Pope had in mind when writing about Chloe was said to be Henrietta Berkeley. She was now happily occupied with her husband and with decorating and redecorating her house at Marble Hill. This was at the expense of maintaining the sympathetic correspondence that her friends had received from her during her miserable court servitude. Her happy home life meant that her former friendship with Alexander Pope had soured on his part to jealous disgust.

Elsewhere in London, Molly Hervey, returned from France, had also been seduced by the new mania for decorating. She commissioned the architect Henry Flitcroft to design a house in St James’s Place. She mocked both it and her gout: ‘the one my amusement (for old people must not pretend to pleasures), and the other my torment’.

111

Now well used to her independence, her husband long gone and her eight children grown up, she enjoyed choosing her surroundings to please herself. She described herself as ‘deeply’ rooted in her garden, and wished that her plants would ‘flourish half as well’ as she did.

The formerly sylph-like Molly was growing comfortably fat in middle age: ‘though I can’t say I have run up in height, yet I have

spread

most luxuriantly’.

112

*

Not far from Molly’s chic London residence, William Kent in 1742 was working on a similar house in Berkeley Square for one of Princess Amelia’s ladies.

113

But he was about to fall worryingly and ‘suddenly ill of his eyes’.

114

Kent was now living in his own little house nearly next door to his old friend the Earl of Burlington at Burlington House. His eye strain should have been a warning that his health needed more attention, but he still hadn’t discarded his feckless, pleasure-seeking lifestyle. In one of his letters Kent presents an amusing vignette of himself, the grumpy artist, being cured of a hangover by looking at pictures. In his customary telegraphese, Kent told a friend that one morning Alexander Pope had come round to his house ‘before I was up, it had rained all night & rained when he came I would not get up & sent him away to disturb somebody else – he came back & said could meet with nobody’.

So Kent reluctantly got ‘drest & went with him’. Off they strolled to an art dealer’s, where they looked at pictures ‘& had great diversion’.

115

Yet Kent and his chums were clearly overindulging their middle-aged bodies: one of Lord Burlington’s daughters would write archly in 1743 that Mr Kent ‘took all the

potted hare with him so I can’t tell his opinion of it yet, but I dare say he will like it wondrously’.

116

A life of ‘high feeding and much inaction’ took its toll on the rosy-cheeked Signior