Creature from the 7th Grade : Boy or Beast (9781101591833) (4 page)

Read Creature from the 7th Grade : Boy or Beast (9781101591833) Online

Authors: Andy (ILT) Bob; Rash Balaban

“Why, hello there, Mrs. Drinkwater,” he says at last. “This is Principal Muchnick. I have some rather unusual news for you. Are you sitting down?”

HOME SWEET HOME

IT'S THE MIDDLE

of fourth period. Sam and Lucille get special permission to leave math class early so they can wait with me in front of school for my mom to come and pick me up. A couple of kids hang out windows and stare down at me, transfixed, until their teachers pull them back in again. An awkward silence hangs in the air. Sometimes it's hard to know just what to say when your best friend turns into a giant lizard.

“I almost forgot,” Sam says. “Mr. Arkady told me to give you this.” He hands me a small envelope. I rip it open with the tip of my claw and read the neatly written note:

Â

Dear Mr. Drinkwater,

Please make an appointment to see me at your earliest convenience. I would like to discuss your upcoming report and share a few of my insights with you regarding amphibians, the class to which you apparently now belong.

Â

It's much easier to understand what Mr. Arkady is saying when he writes stuff down.

“What's he want?” Lucille asks.

“He wants to talk lizard with me.” I place the letter carefully into my backpack. “My mother is totally going to lose it when she sees this tail.” I wave it around for emphasis.

“Probably.” Lucille ducks and narrowly avoids getting hit in the face.

“Not to mention what she's going to do when she spots your claws and your flippers and your gill slits,” Sam says, fiddling with his fake nose ring. Sometimes it slips off when he gets excited and you have to pretend not to notice while he reattaches it.

“We left no stone unturned,” Lucille says. “We want you to know that.”

“We looked all over, but we couldn't find a single thing about spontaneous mutation in the human adolescent,” Sam says. “We were online during most of English class.”

“I thought Mrs. Adams was going to send us to detention,” Lucille adds. “And then Sam pretended he was going to the bathroom and went and called his uncle Leon.”

“But he couldn't help us out because he lost his friend at NASA's phone number,” Sam says.

“You did your best,” I say. “What more could you do?”

“I figured maybe you walked into a cloud of radiation and insecticide by mistake,” Sam says. “Like Scott Carey in

The Incredible Shrinking Man

.”

“I thought of that, too,” I reply. “Only I didn't. I would have remembered.”

“Yeah. That's what Lucille said.”

“We did an extensive search on SpaceWeather.com for signs of recent meteor showers, extreme sunspot activity, or unusual lunar occurrences,” Lucille says. “Renegade electromagnetic forces have been known to cause some pretty unusual effects on people. Look at the Wolfman.”

“But we didn't even come up with even one measly little asteroid,” Sam says.

“We checked out more than a dozen UFO Web sites,” Lucille continues. “We thought maybe you had a Close Encounter of the Third Kind and got turned into an alien. We found some pretty credible recent sightings in Ohio. And a couple in Wisconsin,” she says. “But not a single sign of recent extraterrestrial activity in all of central Illinois, I'm sorry to report.”

“So what do you think happened to me?” I hear the

putt-putt

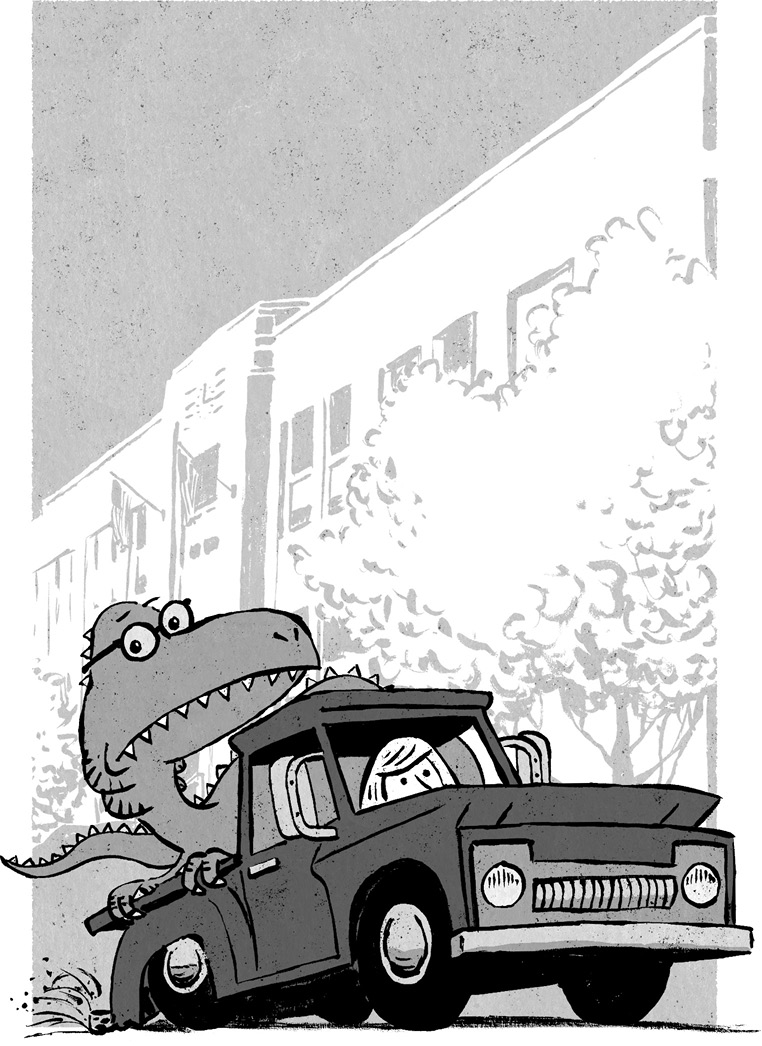

of my mom's old red pickup truck rounding the bend as it slowly approaches school. “Slowly” is its main speed. Its only other one is “even slower.”

“We have absolutely no idea,” Lucille admits. “But there's lots of places we haven't even heard from yet. We're still waiting for

Ripley's Believe It or Not!

to call us back, for example.”

“We're not giving up,” Sam adds.

“Of course we're not,” I say. “We're Junior Scientists of America. We can figure out anything.”

“Whatever happens, I have two words of advice for you, Charlie,” Lucille says as my mom drives up. “Wear deodorant.”

Mom's truck lurches to a halt in front of the building and backfires loudly. Several times. You wouldn't want to enter any races with our truck, but it's good for hauling around stuff and for quick trips to the grocery store. And picking up your son from school when he turns into the Creature from the Seventh Grade.

“Hey, Charlie!” my mom calls out cheerfully. “Hop in the back. You're waaay too big to ride up front with me.”

“Your mom seems to be handling the situation awfully well,” Sam whispers as I pull down the tailgate and haul my massive body onto the truck bed. My tail is so long that it hangs over the side, nearly touching the ground.

“I don't get it,” Lucille says.

“She probably knows how to fix me,” I say hopefully. “She's really good at repairing stuff.”

“All aboard!” Mom shouts.

“Call you later,” Lucille says as she slams shut the tailgate and hurries back to class.

“Ditto,” Sam yells.

“Double ditto,” I cry back.

“So long, kids,” Mom hollers, and I hunker down as she tries to pull away.

“Tries”

is the operative word here. The engine whines and strains. And then dies. She turns the key to start it again, and I can feel the gears grinding as she shifts into neutral and back into first. And we're still not budging. I am much too heavy for this old truck to handle. You can smell the oil burning in the carburetor. A thin trail of black smoke rises up from under the hood. I pray no one takes a picture of this and posts it on the Internet.

Just as I am about to give up hope of ever moving, the engine finally turns over, and the truck starts up. I look back at my school getting smaller and smaller as we chug down the road. I hold on to the sides of the truck with my claws to keep from falling out. It's really bumpy back here.

When we stop at the light on the corner of Fifth and Lonesome, passersby gawk at me. I greet them with a cheery wave of my tail and a friendly “It's me, Charlie, only big and green,” hoping to avoid a panic in the streets. It's not working. Our neighbor Mrs. Pagliuso stares at me so hard that she walks right into a tree. A terrified babysitter pushing a buggy grabs the baby in her arms when she sees me and runs off in the opposite direction.

Before you can say, “My son looks like something that just escaped from Jurassic Park,” we're in our driveway, pulling up to the garage. Balthazar makes a mad dash out of his doggy door, barking an enthusiastic hello, before he takes one look at me, screeches to a halt, and heads for the nearest tree. In five seconds flat, my ninety-five pound Labradoodle is halfway to the top, clinging to a branch for dear life and howling like a wounded banshee.

My mom gets out, marches over, lowers the tailgate, and waits while I maneuver my enormous hulk of a body onto the lawn and head for the house. As I walk I leave giant webbed footprints in the grass.

“You run inside and scrub those claws and I'll go put on a big pot of hot cocoa,” Mom says. “Your father will be home soon. We'd like to have a little chat with you, honey.”

Mom holds the kitchen door open and motions for me to come in. I am so tall I have to stoop over so the top of my head doesn't crash into the door frame. I am so wide I have to squeeze myself through the opening.

Just as I get inside, my dad's bright-yellow Toyota careens around the corner and races up the driveway. Dad jams on the brakes, jumps out of the car, and runs toward the house.

“I thought I'd never get here.” He hugs Mom and hangs his hat on the doorknob.

“Look who's here, Fred,” Mom says, pointing at me.

“Good to see you, son. You're looking very green.” And with that my dad gives me a big smile and a pat on my big green slimy shoulders, like he's used to seeing giant green scaly creatures in the hallway on a regular basis. When he thinks I'm not looking, he wipes the creature goo from his hand onto his pants leg and we all head for the kitchen.

I accidentally whack my dad on the side of his head with the tip of my tail as I turn to wash my claws in the sink. He moans quietly and clutches his ear. “Sorry, Pop,” I say, wiping my claws on one of mom's favorite dish towels and trying not to rip it to shreds. “I'm having a little trouble getting used to my tail.”

“Who isn't?” my dad says jovially, as he drags out the sturdy wooden milk crate my mom uses to store her cookbooks, pulls it up to the kitchen table, and gestures for me to sit down.

Mom carries over mugs of steaming sugar-free cocoa with miniature nonfat marshmallows floating on top. “Careful, Charlie,” she warns as she sets them on the table. “It's awfully hot.”

I stick out the first few feet of my enormous tongue and carefully lap up a little of my favorite hot beverage. “Can I get you some cookies?” Mom asks.

“Yes, please.” I try not to sound too eager, but I am ravenous.

When my mom comes over with a freshly baked batch of her famous low-calorie butterscotch melt-aways, I quickly spear the bite-sized treats with the tip of my pointy tongue and shovel them into my cavernous jaws.

Mom's a great cook. She runs a catering business for people on restricted diets called Slim Pickings. She works out of the house. That's how come she was home when Principal Muchnick called. Dad manages a sporting goods store downtown called Balls in Malls. He usually works late on Mondays. But apparently not this Monday.

“Manners, Charlie,” Dad says under his breath as he sits down next to me and hands me his handkerchief. I take it in my claws and politely dab at the crumbs clinging to what passes for my mouth.

“I think it's time we had our little chat, sweetie,” Mom says, smoothing the front of her dress and taking her seat at the table. She gives Dad a gentle poke in his side with her elbow. “Don't you think so, Fred?”

Good. This is the part where my parents explain what's happening and tell me everything's going to be all right.

Dad takes a big gulp of hot chocolate, sets his mug aside, and looks me squarely in the eye. “Charlie, your body is going through some pretty big changes,” he begins.

“Yeah. I noticed,” I say, holding up both my claws and waving my tail at him.

He continues, unfazed. “Changes that may have cause you to feel embarrassed, self-conscious, awkward, and out of control. Do you catch my drift, son?”

“I caught it.”

“Your mother and I want to assure you that these changes are a perfectly normal part of growing up and becoming an adult,” Dad says matter-of-factly.

“They are?” I ask, stunned.

“Absolutely, honey.” My mom gently takes one of my claws in her hands, careful not to cut herself on its knifelike edges. “Welcome to adolescence, Charlie.”

“

That's

what this is?”

“There comes a time in every young man's life when he undergoes . . . uh . . . a certain, shall we say, life-altering process,” my dad explains. “Only in some cases, the process happens to be a little more . . . uh . . . life-altering than others. Like . . . um . . . yours, for example.” My dad always gets nervous when he has to talk about personal stuff. He would much rather talk about baseball. Or the weather. Or anything.

“I would really like to know what's happening to me, Mom. I don't understand what Dad's trying to tell me.”

“The facts of life,” Charlie,” Mom replies. “Plain and simple.”

I thought I was already pretty well informed about this whole “facts of life” business. Boy, was I wrong. The “facts of life” are neither plain nor simple. At least not in the Drinkwater household.

THE BIRDS AND THE BEES AND THE MUTANT DINOSAURS

ACCORDING TO MY

father, the Drinkwater “facts of life” began nearly sixty million years ago, when a cataclysmic meteor shower struck the earth with such force that it wiped out most of the dinosaurs on the planet. “But a few hardy specimens from a little town that just now happens to be called Decatur, Illinois, survived and underwent a dramatic mutation,” Dad explains.

“Can you imagine, Charlie?” Mom says. “The only remaining dinosaurs in the whole world lived in our own backyard? Isn't that amazing?”

“I guess so,” I reply weakly. I am getting more confused by the minute.

“Before they died, these brave creatures laid eggs containing genetically altered baby dinosaurs, son,” Dad continues. “And when they hatched, the babies turned out to be amphibians.”

“Do you know what an amphibian is, Charlie?” my mother asks.

“Of course I know, Mom,” I say impatiently. “We're studying them in science class. They can live in water and on land. Salamanders are amphibians. What does any of this have to do with me?”

“I'm getting there,” Dad says, “hold your horses. Those mutant dinosaur babies survived their hostile environment by heading straight for the bottom of the lake that had been formed when one particularly large meteor landed near their swamp. That's Crater Lake, Charlie.”

“Crater Lake! Can you believe it, honey?” Mom exclaims. “We took you there to learn how to swim when you were just four. You loved that place.”

For the record, I hated it there. Too many mosquitoes, the sand got stuck between my toes, and it smelled like rotting logs.

Mom continues. “And then sixty million years later, one adventurous young female mutant got tired of life underwater, swam to the surface of the lake, and climbed out onto the shore. She discovered she could breathe air as well as water, so she decided to stay.”

“Quite a story, Charlie, don't you think?” my dad asks.

“Yeah. Very interesting. I only have one question.

WHY ARE YOU TELLING ME THIS??????

”

Mom says, “You see, that adventurous young female mutant creature grew up to become your grandmother, Nana Wallabird, may she rest in peace.”

“What?” I gasp. “Nana was a

dinosaur

?” I am so stunned I nearly fall off my milk crate. “Why didn't anybody tell me?”

There is a long, awkward silence before my mom answers. “We thought it would upset you.” She speaks so softly I can barely hear her.

“You thought it would upset me, so you didn't tell me my grandmother was a dinosaur!”

“A mutant dinosaur,” Dad quickly adds. “There's a big difference.”

“She wasn't as large as a regular dinosaur,” Mom explains.

“Just how large was she?” I ask. Nana died when I was only two. I don't remember her very well.

“About your size, I'd say.” Dad measures the air with his hand. “Seven or eight feet. I'm not really sure. Maybe . . . uh . . . nine.”

“That's pretty large,” I say.

“Yes, but she carried herself like she was smaller,” Mom says. “She was terribly graceful.”

“And very attractive,” Dad remarks. “As mutant dinosaurs go.”

“Can you tell me why Grampa Wallabird married a mutant dinosaur, or will that upset me too much?” I ask.

“Your grandfather had a heart as big as Texas,” my dad explains. “And a nose to match.”

“With feet the size of banjoes,” my mom chimes in. “Not to mention the hump on his back. And that chronic skin condition.”

“Are you trying to tell me that my grandfather was so funny looking only a mutant dinosaur was willing to marry him?”

“Basically,” Dad admits.

My mind is racing as I try to process all this new information. “Okay,” I say. “So I have a little dinosaur DNA in my genome. I guess that explains why I turned into one. But maybe it's just temporary. I could be the Creature from the Black Lagoon for Halloween and then change back into myself for Thanksgiving. I mean, stranger things could happen. They already did. Right, Mom?” I'm beginning to feel a little better.

“Don't get your hopes up, honey,” Mom replies.

“Why not?” I ask.

“You won't be changing back,” she says. “Trust me. I know.”

“But how do you know, Mom?” I persist.

“Parents know these things,” she says quietly.

“Take it from your mother, Charlie,” Dad says. “She knows.”

“You mean I'm going have to stay this way permanently? As in forever????????? With scales and a tail and gill slits . . . and . . . and . . . everything?” I wail.

“Yes,” Mom says softly. “Now you're upset.”

“Upset????????? Mom, they don't even have a word for what I am. All this time you knew I was going to turn into a mutant dinosaur and you never even mentioned it?????????”

“That's the thing, honey,” Mom says, wringing her hands. “We didn't know for sure it was going to happen, so we decided to spare you the unnecessary anxiety. We told your brother that he had a recessive mutant dinosaur gene, and he was so traumatized he failed math and practically got himself kicked off the baseball team.”

“And after all that, he never even grew flippers or a tail or anything,” Dad explains. “So we kind of assumed . . .”

“We assumed your recessive mutant dinosaur gene would stay recessive like your brother's,” Mom says. “Until we got that call from Principal Muchnick today.” Mom turns away from me, her eyes well up, and she starts to cry.

“How am I going to face everybody? What am I going to tell them? âBeing the shortest boy in the entire middle school wasn't bad enough, so I had to turn into an overstuffed chameleon'?”

Mom dries her eyes, blows her nose, and tucks her hanky back into her pocket. “So you're a little different. Big deal. Different is good. Nana Wallabird was different. And she had a wonderful life.”

“She married a guy who looked like the Hunchback of Notre Dame,” I say. I poke around at the marshmallows floating in my cocoa with my tongue. “I wouldn't exactly call that wonderful.”

“Yes, but Grampa Wallabird loved Nana very much,” Dad reminds me. “They were happily married for nearly fifty years.”

“And Nana thought Grampa was the handsomest guy in the world,” Mom says, pouring more hot cocoa into my cup. “Be glad you're not like everybody else, Charlie. You're one of a kind.”

“I sure am. Craig Dieterly always says that when they made me they didn't break the mold, they arrested the guy who made it. I don't even want to think about what he's gonna say about me now.”

“He's just jealous of you, honey. There are a million Craig Dieterlys in this world,” my mom says. “But there's only one Charles Elmer Drinkwater. And don't you ever forget it.”

“Do you have to say my middle name, Mom?” I complain.

“You're special, honey,” Mom says. “Get used to it!”

“I don't want to be special!” I protest. “I want to be like everybody else. Who wants stupid old flippers and a tail and gill slits? Why couldn't I at least be a mammal, Mom? Or even a reptile? It's not fair!” I stomp my flippers on the floor so hard the chandelier begins to shake.

“You should thank your lucky stars, son,” Dad says. “With diversity like this, you could get a full scholarship to any university in the country. Maybe even . . .” he pauses dramatically “. . . Harvard. Who knows?”

“I don't care!” I wail. And stomp even harder.

“Harvard, Fred? Can you imagine? Our little peanut?” She begins to cry all over again. “Our little boy is finally growing up. It's all happening so quickly.”

“I want to be human!!!” I scream.

My dad puts his arm around her. “If it's any consolation, Doris, emotionally he's still just a child.”

Suddenly Dave clomps into the house, cradling his arm. “I strained my left wrist,” he announces as he barges into the kitchen. “Can you believe it? Coach Grubman sent me home in the middle of the practice game. I have to ice it every fifteen minutes and apply heat in between. The play-offs are Thursday. I don't know what I'll do if I'm not better by then.” He grabs an ice pack from the freezer, wraps it around his wrist, then looks up and suddenly notices me. “Hey, look who inherited the Drinkwater family curse. Tough luck, bro.”

“Yeah,” I reply. I'm still so upset I could weep. Only it's totally uncool to cry in front of your big brother. “I was sort of hoping it was temporary.”

“It's not,” Dave says, tightening the Velcro straps on the ice pack. “Curses rarely are.”

“We don't call it a curse, Dave,” Mom says, putting down her hot cocoa. “Let's not make value judgments, sweetie. Charlie is special. We must learn to celebrate our differences. Don't lick the floor, Charles, it isn't sanitary.”

I immediately stop picking up crumbs and reel in my enormous tongue. “Sorry, Mom.”

“We're all unique in one way or another,” Mom continues. “Your father went bald when he was still a teenager.”

“Doris, please . . .” My dad hates it when anybody mentions his lack of hair.

“Never be ashamed of being bald, Fred. I love that shiny head of yours. You know why? Because it gives you character and makes you strong. Poor Al Swanson has the hair of a Greek god, and what good did it ever do him? He still can't sell his way out of a paper bag.”

Poor Al Swanson sells baseballs, mitts, and Ping-Pong paddles at Balls in Malls, the store my dad manages. My mother has been calling him “poor Al Swanson” for so long I used to think his first name was actually Poor.

Mom goes over to my dad, puts her arms around him, and gives him a big kiss right on the top of his shiny bald head. “Your father was the youngest assistant manager in the history of the company. He made head of regional sales before his thirtieth birthday, and if he had all the hair in the world I couldn't love him any more.” She kisses his head again.

“Thanks, Doris. You can stop kissing my head now.” Dad pretends to be fed up. He loves my mom a lot. He just doesn't like saying it out loud.

“Now that we're all done celebrating our differences, isn't anybody going to ask me about how my practice game went today?” Dave asks.

“How did your practice game go today, honey?” Mom asks.

“It doesn't count if I have to ask you to ask,” Dave answers.

“How'd you do, son?” Dad asks. “I'd really like to know.”

“I scored four touchdowns before my injury.”

“Not bad, Dave,” Dad says proudly. “Not bad at all.”

“Yeah. I would have broken an intramural record, Pop, except for . . .” He points to his wrist and the ice pack.

“You boys go upstairs and start your homework while your father and I make dinner,” Mom orders.

“And don't forget to put some heat on that injury,” Dad reminds Dave.

“I'm all over it,” Dave replies.

“If I don't get accepted back into seventh grade, do I still have to finish my homework?” I ask, picking up my crate and taking it upstairs with me.

“You most certainly do,” Mom says. “Now shoo! Both of you.”