Criminal Minds (45 page)

Authors: Jeff Mariotte

The walls of his makeshift bedroom were decorated with crudely fashioned death masks made from the faces of dead women. He had ten female heads, including that of Mary Hogan, a popular saloon keeper who had disappeared three years earlier. Worden’s head had been prepared for hanging, with twine threaded through the ears, but Gein hadn’t had a chance to put her up yet. Her heart was in a pot on the stove. The authorities also found Gein’s mammary vest, the one he wore to pretend to be a woman. It had straps on the back, and he admitted to wearing it with human “leggings.”

When the sheriff and his men tore down the boards that closed off the rest of the house, they discovered that part of it was preserved just as it had been more than a decade before, when Augusta Gein had ruled the home.

Gein denied any murders other than those of Worden and Hogan, although he was suspected of at least nine. He also denied engaging in necrophilia, but there was clearly a sexual component to his crimes, and he was never known to have had a sexual relationship with a living woman. He denied cannibalism as well, but he’d been known to give people “venison” even though he had never hunted deer. His treasures, he insisted, had been dug up from forty different graveyards, but he hadn’t killed for most of them.

Gein and the entire locale of Plainfield became instant worldwide sensations. Reporters flocked to the Wisconsin farming community. Children told jokes called “Geiners” (Q: What did Eddie Gein say when the hearse drove by? A: Dig ya later, baby!).

Gein was sentenced to the Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Waupun, Wisconsin. After ten years there, he was deemed competent to stand trial, but he was quickly judged not guilty by reason of insanity and returned to the hospital. He never left again except to be transferred to the geriatric ward of the Mendota Mental Health Institute, where he died from cancer on July 26, 1984. Gein was buried in the Plainfield cemetery, near his mother and the graves he had robbed. Together again, at long last.

18

The Real Profilers

THE LEGENDARY J. EDGAR HOOVER

, director of the FBI from 1924 until he died in 1972, left a mixed but lasting legacy. In some ways, he turned the bureau into his personal investigative agency: running roughshod over the rights of citizens, keeping files on actors and activists alike, and being willing to use the fruits of the bureau’s investigations to persuade members of Congress and even presidents to do his bidding.

, director of the FBI from 1924 until he died in 1972, left a mixed but lasting legacy. In some ways, he turned the bureau into his personal investigative agency: running roughshod over the rights of citizens, keeping files on actors and activists alike, and being willing to use the fruits of the bureau’s investigations to persuade members of Congress and even presidents to do his bidding.

At the same time, he turned the bureau into the world-class crime-busting operation it is today. He decentralized it, creating field offices around the country so the response to crime could be immediate. He created the FBI laboratory that began in humble digs in a room at the Old Southern Railway Building in Washington, D.C., and has grown into the premier lab of its kind. Long before Miranda was the law of the land, he insisted that suspects be treated with dignity, that they be warned of their rights, and that the reports that agents filed about them be honest. He invented the Ten Most Wanted list. And he believed in the importance of training his agents.

One of Hoover’s final and most important acts was the creation of the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia. The academy opened its doors in 1972, three days after Hoover’s death. It serves to train new FBI agents, to keep agents informed about new developments in criminal investigation, and to train other law enforcement officials in the techniques the FBI has learned.

Before Quantico, police officers could train with FBI agents at the National Academy. The National Academy functioned to instill greater professionalism among police officers and to help the FBI develop a national network of officers with whom it had good relations. One of the academy’s instructors, a former California cop named Howard D. Teten, had read Dr. James A. Brussel’s accounts of his own experiences with the psychological profiling of criminals, and he was impressed with much of Brussel’s approach.

At Quantico, Teten and Patrick J. Mullany, a field agent from New York who had a degree in psychology, together became the driving force behind the bureau’s new Behavioral Sciences Unit (BSU), which was established in 1972. They developed a new method of analyzing unknown offenders based on the details of their crimes, particularly through careful analysis of the crime scene. The agents who formed the BSU taught this method to other agents and police officers at Quantico, and they also went out on the road to speak to law enforcement officials wherever they could.

At the same time, the BSU began to get requests from police agencies for assistance with unsolved crimes. One of the earliest requests, a plea from the Bozeman, Montana, field office for help with a kidnapping case, resulted in a profile that eventually helped to pinpoint serial killer David Meirhofer. As more and more requests flooded in, the unit grew. It also, at Robert K. Ressler’s urging, created a program that brought agents interested in profiling to the academy for training, then sent them back to their field offices, where they could provide profiling expertise and act as coordinators whenever agencies in their areas requested formal assistance.

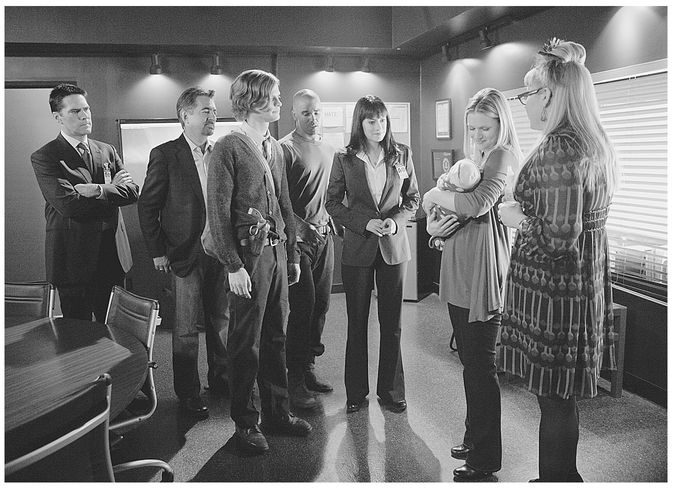

Agent Jareau brings her new baby boy to the BAU offices and introduces him to her colleagues in “Normal.”

To further their knowledge about crimes and criminals, the members of the BSU interviewed a series of assassins and would-be assassins, including Arthur Bremer, Sirhan Sirhan, James Earl Ray, and others. Eventually, that program expanded to include interviews with many serial killers, serial rapists, and child molesters. As the profilers’ understanding of the psychology of these offenders grew, their profiles became more precise and detailed.

Profilers point out that their profiles can’t lead investigators directly to a suspect. They can say what type of person might have committed a given crime, but they can’t magically conjure up a name and an address. Moreover, the information they get has to be as complete and as accurate as possible, because mistakes or disregarded facts can alter the profile significantly enough to make it worse than useless. Profilers think of profiling as a science, but not an exact one.

Many of the profilers working in the BSU—which came to be called the Investigative Support Unit during John Douglas’s tenure—in those days (the 1970s and 1980s) became household names, at least in households with an interest in crime and law enforcement. In addition to Teten, Mullany, Ressler, and Douglas, Roger DePue, Dick Ault, Roy Hazelwood, and Gregg McCrary all worked in the unit when it was growing into the outfit that would inspire best-selling books, movies, and TV shows—and they were helping to identify some of the worst criminals ever to walk U.S. soil.

Ressler and an agent named Jim McKenzie looked at ways to spread the FBI’s work, to make its resources more accessible to police departments around the country. Their idea, which would put the BSU and other aspects of criminal investigation under a single umbrella, became the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime, or NCAVC.

Independently, a police detective in Los Angeles named Pierce Brooks—the man who had headed up the Harvey Glatman investigation in the late 1950s—had proposed a computer system that would link all of the police departments in California so that the details of all of the violent crimes that occurred in one jurisdiction would be available to everyone. When Brooks first proposed it, California’s budget couldn’t accommodate it. But decades later, Brooks, after a distinguished law enforcement career, had brought the idea back and received a U.S. Department of Justice grant to study the feasibility of what he called the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program (ViCAP).

The FBI liked Brooks’s idea, but it thought that his proposal for structuring it was too limited. Instead, the bureau convinced him to bring it under the NCAVC umbrella, which he did. Brooks managed ViCAP, which is now, in the FBI’s words, “a nationwide data information center designed to collect, collate, and analyze crimes of violence.”

Today, NCAVC describes its mission as combining “investigative and operational support functions, research, and training in order to provide assistance, without charge, to federal, state, local, and foreign law enforcement agencies investigating unusual or repetitive violent crimes, communicated threats, and other matters of interest to law enforcement.”

The agency is divided into four components: ViCAP; Behavioral Analysis Unit 1 (BAU-1), which deals with terrorist threats; Behavioral Analysis Unit 2 (BAU-2), which is focused on crimes against adults; and Behavioral Analysis Unit 3 (BAU-3), which handles crimes against children.

When agents from the Quantico BAU headquarters do go into the field, as the ones on

Criminal Minds

do, it’s usually to consult on-site with local law enforcement officers who have requested the unit’s assistance, usually through someone in a local bureau office, not an agent, like the show’s J.J. Jareau, stationed at headquarters. The agents visit crime scenes and consider physical evidence, all in the service of coming up with the best, most detailed profile of the unknown offender. But they don’t kick down doors, engage in high-speed chases, or make arrests. They’ re an advisory group, operationally involved in cases, but not, except in very rare instances, with guns drawn. They don’t travel in a pack on a Gulfstream jet, as the profilers in the TV show do, but instead they spend much of their time sitting in front of computer screens, reading case files, and talking to law enforcement on the phone.

Criminal Minds

do, it’s usually to consult on-site with local law enforcement officers who have requested the unit’s assistance, usually through someone in a local bureau office, not an agent, like the show’s J.J. Jareau, stationed at headquarters. The agents visit crime scenes and consider physical evidence, all in the service of coming up with the best, most detailed profile of the unknown offender. But they don’t kick down doors, engage in high-speed chases, or make arrests. They’ re an advisory group, operationally involved in cases, but not, except in very rare instances, with guns drawn. They don’t travel in a pack on a Gulfstream jet, as the profilers in the TV show do, but instead they spend much of their time sitting in front of computer screens, reading case files, and talking to law enforcement on the phone.

There is once again a Behavioral Sciences Unit at the FBI, but more like the original BSU than today’s BAU, it is a training and research unit, not an operational one.

According to the FBI’s Web site, “The mission of the BAU is to provide behavioral-based investigative and operational support by applying case experience, research, and training to complex and time-sensitive crimes, typically involving acts or threats of violence.” The unit does this through the process of criminal investigative analysis, which “involves reviewing and assessing the facts of a criminal act, interpreting offender behavior, and interaction with the victim, as exhibited during the commission of the crime, or as displayed in the crime scene. BAU staff conduct detailed analyses of crimes for the purpose of providing one or more of the following services: crime analysis, investigative suggestions, profiles of unknown offenders, threat analysis, critical incident analysis, interview strategies, major case management, search warrant assistance, prosecutive and trial strategies, and expert testimony.”

Criminal Minds

is not an entirely accurate depiction of the work of real BAU members, but the agents on TV have the same mission as their real-life counterparts. When the BAU is brought into a case, it’s because there is a criminal out there who has already struck and will likely strike again. The agents, in cooperation with local law enforcement, want to figure out who the criminal is and to make sure that there are no more victims. Sometimes it takes years, sometimes more people are victimized, and some crimes are never solved.

is not an entirely accurate depiction of the work of real BAU members, but the agents on TV have the same mission as their real-life counterparts. When the BAU is brought into a case, it’s because there is a criminal out there who has already struck and will likely strike again. The agents, in cooperation with local law enforcement, want to figure out who the criminal is and to make sure that there are no more victims. Sometimes it takes years, sometimes more people are victimized, and some crimes are never solved.

But the dedicated agents of the Behavioral Analysis Unit—whether on TV or in the real world—don’t give up the hunt.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adams, Briggs, et al.

Murder and Mayhem

. New York: Signet Books, 1991.

Murder and Mayhem

. New York: Signet Books, 1991.

Bruno, Anthony.

The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer

. New York: Delacorte Press, 1993.

The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer

. New York: Delacorte Press, 1993.

Brussel, James A.

The Casebook of a Crime Psychiatrist

. New York: Bernard Geis Associates, 1968.

The Casebook of a Crime Psychiatrist

. New York: Bernard Geis Associates, 1968.

Bugliosi, Vincent, and Curt Gentry.

Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders

. New York: Bantam Books, 1995.

Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders

. New York: Bantam Books, 1995.

Cahill, Tim.

Buried Dreams: Inside the Mind of a Serial Killer

. New York: Bantam Books, 1989.

Buried Dreams: Inside the Mind of a Serial Killer

. New York: Bantam Books, 1989.

Capote, Truman.

In Cold Blood: A True Account of a Multiple Murder and Its Consequences

. New York: Random House, 1965.

In Cold Blood: A True Account of a Multiple Murder and Its Consequences

. New York: Random House, 1965.

Carlo, Philip.

The Ice Man: Confessions of a Mafia Contract Killer

. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

The Ice Man: Confessions of a Mafia Contract Killer

. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

Chase, Alston.

Harvard and the Unabomber: The Education of an American Terrorist

. New York: W. W. Norton, 2003.

Harvard and the Unabomber: The Education of an American Terrorist

. New York: W. W. Norton, 2003.

Cheney, Margaret.

The Co-ed Killer

. New York: Walker, 1976.

The Co-ed Killer

. New York: Walker, 1976.

DeMeo, Albert.

For the Sins of My Father: A Mafia Killer, His Son, and the Legacy of a Mob Life

. New York: Broadway Books, 2002.

For the Sins of My Father: A Mafia Killer, His Son, and the Legacy of a Mob Life

. New York: Broadway Books, 2002.

Douglas, John, and Mark Olshaker.

Journey into Darkness: Follow the FBI’s Premier Investigative Profiler as He Penetrates the Minds and Motives of the Most Terrifying Serial Killers

. New York: Pocket Books, 1997.

Journey into Darkness: Follow the FBI’s Premier Investigative Profiler as He Penetrates the Minds and Motives of the Most Terrifying Serial Killers

. New York: Pocket Books, 1997.

———.

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit

. New York: Pocket Books, 1995.

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit

. New York: Pocket Books, 1995.

———.

Obsession: The FBI’s Legendary Profiler Probes the Psyches of Killers, Rapists, and Stalkers and Their Victims and Tells How to Fight Back

. New York: Pocket Books, 1998.

Obsession: The FBI’s Legendary Profiler Probes the Psyches of Killers, Rapists, and Stalkers and Their Victims and Tells How to Fight Back

. New York: Pocket Books, 1998.

Eftimiades, Maria.

Garden of Graves: The Shocking True Story of Long Island Serial Killer Joel Rikfin

. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993.

Garden of Graves: The Shocking True Story of Long Island Serial Killer Joel Rikfin

. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993.

Other books

Kijana by Jesse Martin

Bombs Away by John Steinbeck

Tied Together by Z. B. Heller

A Provençal Mystery by Ann Elwood

Raven's Rest by Stephen Osborne

He Who Lifts the Skies by Kacy Barnett-Gramckow

Immortal by Bill Clem

Melanie Martin Goes Dutch by Carol Weston

Out of Control by Shannon McKenna

Consume Me by Kailin Gow