Cross and Scepter (15 page)

Authors: Sverre Bagge

Regardless of the origin of collective payments, the practice was clearly handled differently in the different countries. Its abolishment in Norway already in the 1270s was exceptional. Danish provincial laws that included this provision were in force until 1683, when they were replaced by Christian V's Danish Law, the first code that applied to the whole of Denmark. The Swedish Code of the Realm of 1350 emphasized individual responsibility and made the punishment more severe. A killer caught on the spot or within twenty-four hours after the murder was liable to the death penalty, whereas afterwards, he could atone by paying fines. If he were to die before the full amount had been paid, however, his heirs would be responsible for the rest. Despite this provision, there is evidence of collective responsibility in Sweden as late as in the seventeenth century.

Royal legislation developed parallel to the expansion of royal justice. The earliest provincial laws of Norway were written down in the late eleventh or early twelfth century and the earliest Danish ones in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century, while in Sweden the earliest written laws are of the late thirteenth century and later. These laws are not codes issued by a legislature and organized in a systematic form, but rather records of what were believed to be the laws of a particular area. These Scandinavian laws have been the subject of much discussion. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the extant written laws were mostly believed to have been preserved orally over centuries and were used as sources for an alleged ancient, common Germanic law. This theory is now almost universally rejected and greater importance has instead attached to the king and the Church, although there is still disagreement about what is old and what is new. Influence from canon law can be traced already in the earliest extant laws, the late-eleventh- or early-twelfth-century Norwegian provincial

laws, but these laws also contain elements that point to a traditional or popular origin. In particular, it would seem that the procedural rules in many cases reflect established practice. In a similar way, some provisions in thirteenth-century Swedish laws resemble statements in early-medieval runic inscriptions.

The royal legislation of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the Danish Law of Jutland (1241), and the Norwegian and later the Swedish Code of the Realm (1274â77 and 1350, respectively) represent something new. They are codes issued by a legislative authority, they show greater influence from Roman and canon law, and they are composed in a systematic way. The Law of Jutland opens with a passage influenced by Gratian's

Decretum:

The country shall be built by law. If there were no law in the country, then the one who could grasp most would have most. Therefore, the law should be made according to the needs of everyone, so that those who are peaceful and innocent may enjoy their peace and the evil and unjust may fear what is written in the law (â¦). The law should not be written for the particular benefit of any man, but according to the needs of everyone who lives in the country.

In contrast to the provincial laws, the written law has now become an authoritative text, and there is some idea of a public authority with the right to define the norms of society, but at this date it is still an open question to what extent cases were settled according to the letter of the law. The king's authority to issue laws was disputed in the Middle Ages as well as among contemporary scholars. Early royal legislators, in Scandinavia as well as in the rest of Europe, often referred to an alleged old law or to general principles of justice to legitimate their decisions, as did Knud VI of Denmark and HÃ¥kon HÃ¥konsson of Norway in their decrees about homicide.

This reasoning takes an even more explicit form in

The King's Mirror,

where the author warns the king as the highest judge

against adhering too rigidly to the letter of the law. Instead, he should judge according to “the holy laws,” namely God's own laws as laid down in the Bible and Christian doctrineâthe Old Testament holds a particular importance here, as most of the examples set up for the king are taken from this source. Although

The King's Mirror

contains no explicit reference to the king as a legislator, its doctrine that the king's duty is to do what is just regardless of the existing laws, lays the intellectual foundations for royal legislation. This idea was developed further by HÃ¥kon's son Magnus in the Norwegian Code of the Realm, according to which the law in the final analysis is anchored in an absolute, objective justiceâGod's own justice, which supersedes the articles of the written law.

However, there were limits to how far this idea could serve to justify the various solutions to practical problems laid down in royal or even ecclesiastical law codes. God could hardly be made responsible for the change from two to three months of military service or changes in the terms of land lease. As in the early period, a certain idea of positive law was a necessary element, only now the question of the authority behind this law was posed more explicitly. When King Magnus issued the National Law, he first presented his plans to the provincial assemblies (

lagtings

) to get permission to carry them out. Having composed the law-book, he presented it to the assemblies once more and had it formally promulgated by them in the years 1274â76 (as the

lagtings

met at approximately the same time in different parts of the country, the king could only be present at one of them each year). He was thus very diligent about seeking the consent of the people, but his actions seem to imply that in giving the king their consent the people had permanently delegated their legislative authority to him. In accordance with the exalted theory of

The King's Mirror

, the king may well have claimed to be the supreme legislator, and he certainly regarded himself and the legal experts in his circle as

vastly superior in wisdom and knowledge of the laws. Another section in the law alludes to the well-known passages in the

Corpus iuris civilis

, according to which the emperor is not subject to the law and his decisions have the force of law.

Although most medieval jurists interpreted these passages in a narrow sense and the exact meaning of the allusion to them in the Code of the Realm is not quite clear, there is no doubt that the Norwegian king claimed considerable authority as a legislator. This is expressed in another statement in the code, which declares that only a fool confines himself to the letter of the law, whereas the wise man considers the background and circumstances in order to apply the law in the best way. Thus, the law has to be administered by the king and his legal experts who, unlike ordinary people, are qualified to adjust it in different ways.

By contrast, there were greater restrictions on the king's legislative power in Denmark and Sweden. In his 1282 charter, which became the model for later election charters, King Erik V Klipping had to promise not to change King Valdemar's law. Consent to or even active participation in legislation became a frequent provision in the later election charters. It is also significant that no law for the whole of Denmark was issued until the king had become absolute (in 1660) and issued the Danish law of 1683. However, the kings issued a series of ordinances, which in practice came to have a similar status to that of laws. Sweden did get a national law in 1350, but it was to a greater extent than the Norwegian one an expression of aristocratic interests.

The emergence of public justice, organized by the Church as well as the monarchy, was an important factor in political centralization and the emergence of an elite, for it created new officials and transferred economic resources and political power from the peasants to the upper classes. Should it then be regarded primarily as yet another means of exploiting the population, or was it a “service function”? Both points of view have had and have their

adherents. Public justice clearly served the interests of the monarchy and the elite, who increased their power and profited from the fines paid by those convicted. From the point of view of the people, its main disadvantages derived from the corruption of royal officials and the fact that public justice was slow justice. In the case of Denmark, it has also been claimed that the new procedures, which would at first seem to us to represent progress, actually weakened the position of ordinary people. Whereas the old formal means of evidence gave a well-connected man in the local community a reasonable chance to acquit himself of an accusation by summoning his neighbors and relatives as co-jurors, the new juries, which could be bribed or manipulated by powerful landowners, made him dependent on an aristocratic patron. In the case of Norway, we have examples of abuses of the system, both from the sagas and from royal complaints, but we do not know how widespread they were. As for the advantages of public justice, it is important to note that the feuds were suppressed not primarily by prohibitions and punishment, but through alternative ways of resolving conflicts. The existence of public justice made it easier to settle legal questions, while at the same time making it possible to abstain from revenge without losing face. It is difficult, in fact, to know where to draw the line between exploitation and common interests. In any case, whether or not the evolution of public justice was consonant with the “objective” interests of the people, the reason for its progress must be sought in ideology more than in direct pressure from above, this in contrast to what happened in the field of military specialization. This is evident from the fact that not only royal but also ecclesiastical jurisdiction expanded during our period, and that the expansion of public justice took place mainly in periods of internal peace and stability.

Despite the fact that our knowledge of the earliest period is, as usual, limited, there can hardly be any doubt that considerable

changes took place in the field of law and justice in Scandinavia from the twelfth century onwards. The oldest legal system can be reconstructed from provincial laws, at least in the field of procedure, while the extant laws must largely have been formulated at the time of writing and show the influence of the Church and the monarchy. We are dealing with a transition from a form of law and justice that regulated issues between equal parties according to formal rules, to public justice, exercised by the Church and the monarchy. This entailed an impartial judge operating above the parties and judging according to his own interpretation of written laws. These changes in law and justice are the clearest expression of how ideas about the right order of the world (discussed above) were applied in practice. Thus, the adaptation of common European law and jurisprudence, which began as early as in the twelfth century provincial laws and was greatly extended in the legislation from the second half of the thirteenth century, had far-reaching consequences. Viewed from an international perspective, the Scandinavian legal system may be regarded as a combination of the English and the Continental variants. As in England, the national legal tradition was largely retained, whereas the existence of law codes as well as influence from Roman and canon law point to continental parallels. The combination of professional judges and popular representatives may also seem to represent a blending of the two traditions, although on this point there are so many different solutions in England as well as on the Continent that it is difficult to make an exact classification. What is clear, however, is that Scandinavia was deeply influenced by the legal revolution that was underway in contemporary Europe. Although the king's growing authority and involvement in legal matters can be explained as a means to extend his power, parallel to what happened in many parts of the world, the particular form this development took as well as the parallel growth of ecclesiastical jurisdiction must be the result of European influence. The

Scandinavian countries thus had the advantage of being exposed to influence from the center at a time when new legal and administrative forms were developing there.

War and the Preparation for War: From

Leding

to Professional Forces

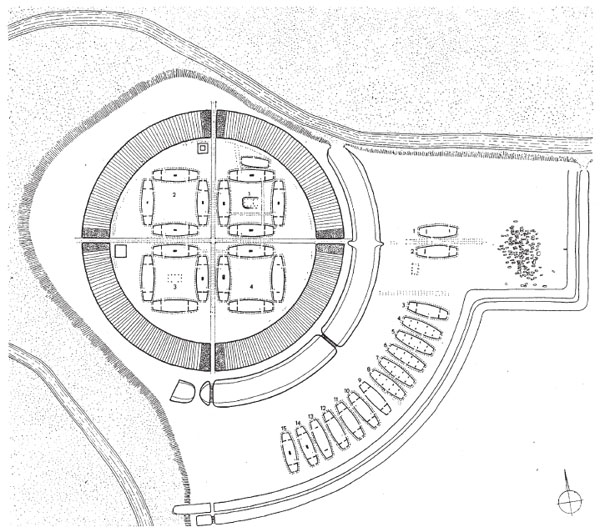

In the mid-twentieth century, four big military camps were excavated in Denmark. They are usually referred to as

trelleborgs

, after the best-known of them, Trelleborg on Zealand. The others are Fyrkat and Aggersborg in northern Jutland and Nonnebakken outside present-day Odense on Funen. Their date was long a subject of controversy, but has now been fixed at around 980 through dendrochronology. Trelleborg has been dated in this way to 981, and although there is not sufficient wood to date the others, the similarities between them indicate that they are almost certainly contemporary. The camps are built in the shape of a circle, varying between 120 and 240 meters in diameter, and filled with houses, placed strictly symmetrically. The date as well as the character of the fortifications indicates that they were built in connection with Harald Bluetooth's conquest, possibly as garrisons to control various parts of the country. They thus give substance to his boast of having conquered the whole of Denmark.

From a military point of view, the trelleborgs differ from the castles that were built some hundred years later in being large and probably low-slung. Although only the foundations have been preserved, they most probably had wooden palisades. They thus would have needed a large number of men to defend them properly. Despite being built to house an occupation force, the number of men needed to garrison them indicates a relatively modest difference between elite soldiers and the common population. The Danish conquest of England shortly afterwards points in the same direction. Although later English sources describe the elite character of Cnut's army, it must have been the result of a large mobilization, for according to one version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle it arrived from Denmark on 160 ships.

Figure 9.

Trelleborg on Zealand. A camp with houses, surrounded by walls and palisades. As the drawing shows, it is built according to a very precise plan, with symmetrical buildings placed exactly in the center. Drawing by Poul Nørlund, from

Nordiske Fortidsminder

, vol. 4, fasc. 1 (Copenhagen, 1948), p. 24. Dept. of Special Collections, University of Bergen Library.