Cross and Scepter (5 page)

Authors: Sverre Bagge

The rise of Kievan Rus may have limited Scandinavian expansion in this area from the late tenth century, which in turn may explain the last phase of Viking expansion in the West, the Danish conquest of England. Another explanation of this is provided, however, by the unification of Denmark under Harald Bluetooth from the middle of the century. The first major raid on England in 991 was led by Harald's son Sven Forkbeard, who in the following years led several expeditions against this country, as did also several other Scandinavian warriors. Finally, in the summer

of 1013, Sven arrived with a large fleet and chased King Ethelred out of the country. He was acclaimed king shortly before Christmas, but died six weeks later. His son Cnut (Danish: Knud) returned a few years later, conquered the country, and ruled England from 1017 until his death in 1035.

In addition to their plundering expeditions, the Scandinavians also settled on islands in the North Sea and the Atlantic. There were contacts between Norway and the Orkneys already in the seventh century and a number of Norwegians settled there, as well as on Shetland and the Hebrides in the mid-ninth century, after having suppressed the indigenous inhabitants. According to the oldest written account, by Ari the Wise, the first settlers arrived in Iceland in 870 and found the island empty, apart from some Irish monks. During the following sixty years, a number of new settlers arrived, mostly from Norway but possibly also from other countries, after which all the available land had been taken. Greenland was discovered in the late tenth century and settled in the following period. Despite its cold climateâwhich was probably warmer a thousand years agoâthe country was rich in pasture, fish, and game and thus attractive to settlers. Some expeditions from Iceland and Greenland also arrived in North Americaâremains of their houses have been found on Newfoundlandâbut there is no evidence of permanent settlement. According to the sagas, the Native Americans made this too difficult.

Various explanations have been suggested for this expansion. One of them is population pressure, leading people to seek new opportunities abroad. There is evidence of demographic growth at the time, expressed in a proliferation of new settlements. Population pressure may also explain why hitherto uninhabited countries, like Iceland and Greenland, were settled during this period. However, it is difficult to explain the Viking expeditions in general in this way. A warlike population does not require population

pressure to turn to plundering abroad; military strength and a knowledge of the wealth to be gained are sufficient motivation. Wealthy and undefended monasteries must have posed a particularly strong temptation. In so far as population increase was a factor, it serves to explain the presence of sufficient manpower, not the incentive for the expeditions.

Rather than seeking an explanation in poverty and need, it seems reasonable to seek it in the awareness of new opportunities. A significant factor must have been the development of seafaring technology.

The Viking ship was fully developed around 800, when it was equipped with sails, although at the same time it remained admirably suited to the use of oars. It was one of the most advanced vessels of its time, easy to maneuver and well able to cross the open sea, whereas European ships kept closely to the coast. Another factor in the Vikings' favor was their familiarity with European countries as the result of increased trade in the previous period. The first Norwegian mentioned by name in history was actually engaged in the fur trade. This was Ottar of HÃ¥logaland, whose narrative of his journey from northern Norway to King Alfred's court in Wessex was recorded in Anglo-Saxon as a preface to a translation of Orosius (below, pp. 131â32.)

The conquests in the later phase of the Viking Age show that the Scandinavians were able not only to organize raiding expeditions, but also to create their own kingdoms and principalities. There is also some evidence of increasing political organization in Scandinavia itself. Rimbert's

Life of Ansgar

and other Carolingian sources from the ninth century mention kings in Denmark and Sweden. A Danish king, Harald Klak, was baptized in Mainz in 826, but was deposed soon after his return to his home country. Although the Swedish kings mentioned in these sources are clearly local chieftains, we cannot exclude the possibility that the Danish kings ruled over larger territories; there is even some evidence that they controlled parts of southern Norway. On the other hand, the use of the title “king” in Carolingian sources need not imply any knowledge of Scandinavian conditions but may simply be a convention for referring to foreign rulers. In any case, we have little evidence either of the size of the territories these rulers commanded and to what extent these territories were regarded as permanent entities. Only from the mid-tenth century onwards is there evidence of a Danish kingdom ruled by one dynasty. This marks the beginning of a major change, the division of Scandinavia into three kingdoms and the introduction of Christianity, which brought them into the European family of kingdoms.

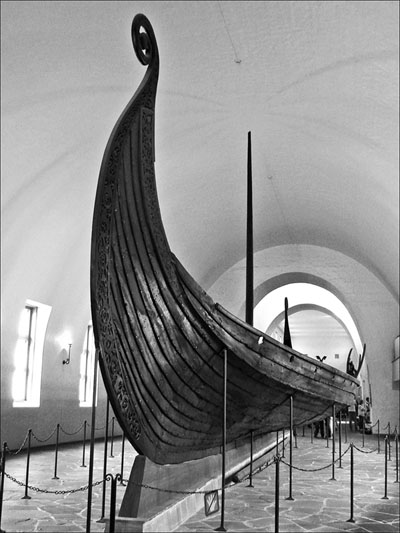

Figure 2.

A Viking ship from a burial mound on the Oseberg farm near Tønsberg in Vestfold (Norway). Built 834, excavated 1904, now in the Viking Ship Museum, Bygdøy, Oslo. The Oseberg burial is one of the most important and well preserved finds from Viking Age Scandinavia, containing a fully seaworthy ship with all kinds of equipment for the burial of a high-ranking woman. The shape of the ship and the details of its construction show its advantages over other contemporary vessels. The Viking ship is light, easy to maneuver and elastic, so that it bends rather than cracks in heavy sea. Photo: Dalbera.

The Division of Scandinavia into Three Kingdoms

In the year 1000, a battle was fought between the kings of the three Nordic countries, celebrated in skaldic poetry as well as by later saga writers. The former depict showers of arrows, streams of blood, and eagles and wolves being fed, while the latter gradually prepare their readers for the final tragedy, the disappearance and probable death of the hero, the Norwegian King Olav Tryggvason. His enemies have prepared an ambush for him and are waiting on shore for Olav's enormous ship, Ormen Lange (=the Long Serpent), believing that one after the other of the large ships passing by is the right one, until it finally arrives and they attack with an overwhelmingly superior force. Spotting his enemies, Olav refuses to flee. He speaks with contempt of the Danes and the Swedes but recognizes his Norwegian adversary, Earl Eirik, as a brave man and a dangerous foe. Olav is proved right; the Danes and the Swedes try to board, but are driven back, while Eirik and his men finally manage to swarm onto Olav's ship and after hard fighting defeat his exhausted and decimated crew. Olav

jumps overboard and is killedâor, as some of the versions have itâescapes and spends the rest of his life as a monk in the Holy Land. Nearly 200 years later, King Sverre of Norway (r. 1177â1202) is said to have mentioned him as the only man standing on the poop of his ship throughout a battle.

The many accounts of the battle in the sagas present the now familiar picture of a Scandinavia consisting of three kingdoms. Although it is doubtful whether we can really reckon with this as early as the year 1000, there is little doubt that the battle was actually fought and that the kings mentioned in the skaldic poetry and the sagas were real persons. It is usually referred to as the battle of Svold or Svolder, an otherwise unknown island off Rügen in northern Germany, where it took place according to the later sagas, but the most likely site is Ãresund, where the earliest sources place it. The battle was thus fought near the later border between the three kingdoms, which is significant, giving a glimpse of an important stage in the formation of the three Scandinavian kingdoms.

The origin of institutions and territorial units is a central problem in historical writings. Consequently, the formation of the three kingdoms occupies a prominent part in the Scandinavian national historiography that developed from the early nineteenth century onwards. Typically, historians dealt with the formation of each kingdom separately, explaining when, how, and why the country was “unified.” The previous sketch has indicated that the formation of larger territorial units may have been less novel than is often imagined. On the other hand, the fact that the previous units seem to have been unstable points to the novelty of what happened in the tenth and eleventh centuries, the formation of the kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. This raises three questions: First, why was Scandinavia divided into these three units only? Second, why did this happen just at this time? And, finally, why did this division become permanent?

The battle of Svolder points to one part of the explanation. It took place at sea, like most important battles of the period, a fact that highlights the importance of sea power. The elegant, well-built Viking ships could move quickly over great distances. And they could carry provisions for considerably longer periods than an army moving over land, which was usually limited to a three-days' march. The Scandinavians could therefore plunder as well as build principalities over the entire area around the North and the Baltic Seas and were in frequent contact with its kings and princes. If we consider the fact that the sea linked localities together, while forests, mountains, and uninhabited land divided them from one another, the division between the three Scandinavian countries becomes quite logical. Jutland, the islands around it, and the low, cultivated land across Ãresund became Denmark, whereas the long coast from the arctic regions to the lands around Oslofjorden became Norway. Sweden could not be controlled from the coast, but instead developed around the great lakes, Vänern and Vättern in the west and Mälaren in the east. Sweden was then separated from Denmark by forest and thinly inhabited land north of Scania. Typically, the most contested area was the coastline between present-day Oslo and Ãresund, the meeting-place between all three countries.

The exact borders of each country of course also depended on its relative strength and on luck, energy, and the degree of dynastic continuity of its sovereigns. Denmark was clearly the strongest of the three, in the Viking Age as well as later. As we have seen, a Danish kingdom may possibly be traced back to the late eighth century. There then seems to have been an eclipse for about a hundred years (c. 850â950), either because the kingdom dissolved or because the decline of the Carolingian Empire put an end to attempts to Christianize and subordinate the Danish rulers, and thus to information about Denmark in Carolingian sources. A revival then occurred with Harald Bluetooth, who in the inscription on a Jelling Stone boasts of conquering the whole of Denmark and Norway and making the Danes Christian.

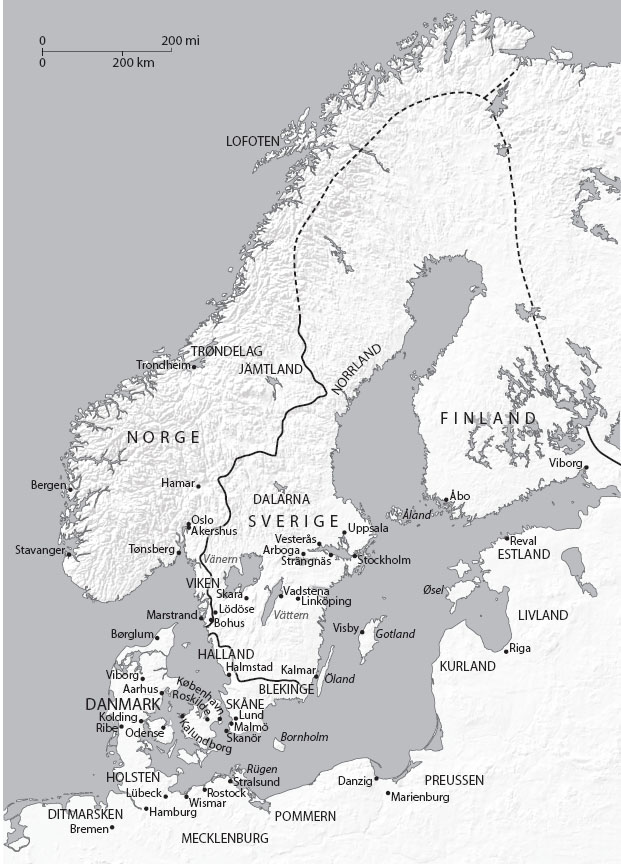

The Scandinavian Kingdoms in the Middle Ages. Map by Poul Pedersen, from

Danmarks Nationalmuseum: Unionsdrottningen

.

Margreta I och Kalmarunionen

(Copenhagen, 1996), p. 425.

Harald Bluetooth was the father of the King Sven who fought at Svolder. The same Sven was a great warrior and Viking chieftain who later conquered England and who hardly conformed to the scornful picture of him that we get in the sagas, where he is the instrument of his wife Sigrid who wants revenge because Olav has slapped her face, and the leader of the “soft” Danes who preferred to lick their bowls during pagan sacrifices rather than expose themselves to danger in battles. Against the background of the Jelling inscription (see

illustration in chapter 3

), as well as the following story of Sven's son and successor Cnut the Great conquering Norway, the battle of Svolder forms evidence of the power of Denmark at the time, a power that increased further as a consequence of the Danish victory, which replaced Olav with the earls Eirik and Svein, both clients of the Danish king.

According to the sagas, the kingdom of Norway was as old as that of Denmark, being the result of Harald Finehair's conquests in the late ninth century and later ruled by his descendants. Nevertheless, the sagas admit that the kingdom was divided after Harald's death (c. 930) and that various pretenders, including the Danish kings, fought over the country in the following period. Actually, the dynasty was probably less and the Danish influence more important than the sagas suggest. The Danish kings continuously intervened in Norway, using Norwegian pretenders as their clients and deposing them or trying to do so when they became too independent. This seems to have been the case with the last of Harald's descendants, the sons of his eldest son Eirik, who came to power with Danish aid but were replaced by Earl Håkon of Lade in Trøndelag, who was in turn succeeded by Olav Tryggvason. It is known from English sources that Olav fought on the Danish side against the English in the 990s, but he was baptized and confirmed with the English King Aethelred as his godfather

and may have received aid from him when returning to Norway. The site of his last battle, Ãresund, well within what must have been the Danish realm, suggests that he was the attacker. Considering the relative strength of the parties, it was probably a preemptive strike or just a raid, not an attempt to conquer Denmark.